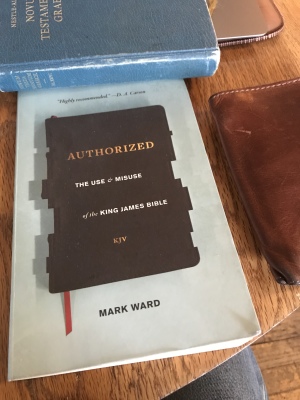

If you love the King James Bible, or if it is the only (or primary) version that you use, you should read the new book “Authorized: The Use And Misuse Of The King James Bible.” The book can by purchased here. A video summary clip can be watched here.

An interview with the author about the book at Exegetical Tools can be found here. Mark Ward, Logos Pro, and PhD from Bob Jones University, has just published the marvelous little book. It approaches the question of whether the King James Bible is the only English translation that should be used by English-speaking peoples. This view is sometimes called “King James Onlyism,” a term that has the unfortunate disadvantage of lumping together a group of people who hold rather distinct views. I grew up holding such views, and I have a good number of friends who l love dearly and respect who still hold such views. (Some of you may even be reading this – Hello!) I find myself using the term “King James Only” often (KJVO for short), though I try to always be mindful of the differences, for example, between those who think the English words of the KJV improve upon the Greek words originally written by Paul, and those who say they only think that the KJV is the best translation currently available in English of what they consider a perfect text (sometimes called “Textus Receptus Only” or TRO for short). There are loads of other variations, and some far more moderate explanations from folks whom I would never give the “only” title to.

Is The King James The Only Right English Bible?

This is by no means the first book to touch on this touchy topic. And I usually recommend that folks read the best works from both sides of any issue they are considering. A few good books on the topic, disagreeing with a KJVO position, have been written by D. A. Carson, James Price, James White, and a handful of others. On the other side, literally scores of books have been written to defend a KJVO position. However, I could never recommend most of them to anyone, as many of them are among the most vitriolic, hateful, and often downright unchristian literature I have ever read in my life. It grieves my heart to see people who name the name of Jesus write such words. They have almost created their own genre of writing — an angry genre that has made bolded+underlined+all-caps words a kind of regular way of screaming at the reader in print the way some scream orally in the pulpit. One that uses slander and misinformation as the building blocks for much of what is said. One that strangely often adds literally zero information to the discussion, repeating the same things said in other KJVO works, occasionally almost verbatim.

But a few works are worth mentioning that do a better job than most of them at attempting an irenic approach – a hard if not impossible task, given their position on the topic. (After all, how can one be truly irenic when they believe they have the Word of God and everyone who disagrees with their position does not?) For example, the work by R. B. Ouellette, (see my sadly unedited, but hopefully still helpful, review of Ouellette’s work here) and a few works by Vance, are both far better than most in presenting a Christian spirit of kindness and respect in their works. I am grateful for their works. These are the only ones I ever refer others to when trying to explain “both sides” of the issue. But this book is distinct from those works in a number of ways, which make me want to share and recommend it in a way that I have never wanted to broadly share or recommend those other works before.

What Makes This Book Unique?

I would suggest that three things make Ward’s book unique among books written about this issue.

Respect For The King James Bible

First, Ward is incredibly respectful of the King James Bible. He does not say a single negative word about the King James Bible in the entire book. He does not one time seek to correct the Translators, their translation work, or the Greek and Hebrew texts they were translating from. Not once. He shows nothing but a deep respect and appreciation for the time-tested and God-honored work of that group of godly men. You will not find here some angry rant about how everyone should throw out their KJV’s. Rather, he encourages it being read regularly. His chapter on, “Five Things We Lose as the Church Stops Using the KJV” is a marvelous call for the Church, and families, to retain the KJV in some ways, and to use it properly. I don’t know another work on the topic that shows such a level-headed position, from such a respectful stance. Perhaps my own life would have been different had I come across such a level-headed case for the KJV back when I was searching in my heart for some reason to hold on to my belief that the KJV was the preserved Word of God for the English-Speaking People.

Respect For People Who Only Use The King James Bible

Second, Ward is incredibly respectful of those who disagree with him. Even when they disagree sharply. He doesn’t think you should “only” use the King James. In fact, he firmly believes that no one should “only” use any one version. To even suggest such a thought is in some circles tantamount to apostasy, and members of such circles are often quick to throw such charges around. I know – I’ve been called an agent of the devil, an apostate, an unbeliever, and told that God should take my life for my “sin” of no longer defending the KJV (and daring to suggest to others that they shouldn’t be KJV Only either). And this was sadly mostly by people who I consider friends and family. Many who find such mud slung at them find it hard to resist the temptation to sling some back. Ward resists such urges and takes a higher and more Christian path. I am humbled (and convicted) by the clear fruit of the Spirit in his tone and demeanor. Love, understanding, respect, and compassion spills off of practically every page for all who only ever use the King James, and even for those who demand angrily that no one ever use anything else. I read most of the works I listed above while I was still KJV Only, and one of my problems with works like those has always been that they didn’t seem to fully understand what it was that we believed, and/or weren’t all that compassionate or irenic in their attempts to correct us. Some handle the issues themselves decently (like White, who’s work mostly responds to the extreme end like Riplinger), but simply aren’t understanding and compassionate in their approach to the very people they are trying to reach.

I no longer hold either a KJV Only or a TR Only position (as I explained here), and today I regularly use a number of good translations (reading most often at the moment from the ESV, but also regularly from the NIV, NLT, and KJV, as I recommended here). But I doubt any of the works I have seen written on this topic would ever by themselves have convinced me, while I did hold those views, to change my mind. (In fact, I was incapable of changing my mind until the Gospel first changed my heart – but that’s another story for another post. I explained the technical details of why I changed by mind at length in an article here.) I think Authorized is unique in this love, respect, and understanding of its audience.

An Easy And Enjoyable Read

Third, Authorized is utterly readable. Ward makes the point throughout that Paul linked together intelligibility and edification. There’s a biblical principle that we must first understand what is being said before it can edify us. “So likewise ye, except ye utter by the tongue words easy to be understood, how shall it be known what is spoken? (1 Cor. 14:9a KJV).” He thus sees no point in discussing Greek and Hebrew manuscripts, or the details of textual criticism, or translation technique. With rare exception, those who hold to any kind of position that demands the sole use of the King James Bible have a minimal knowledge of such issues (and sometimes see such a minimal knowledge as a virtue). Ward feels that discussions about such technical issues will ultimately end up being nothing more than a, “You trust your experts, and I trust mine” type of logistic standoff. So he doesn’t go there at all. No Greek words here. No Hebrew words. No images of impossible-to-read ancient manuscripts. Just plain, simple, enjoyable, easy-to-understand English. I think William Tyndale would be proud of how he has taken the complex and made it very simple. You will not find this book hard to read. You will probably find it quite enjoyable, whether you ultimately agree with the author or not.

So I’m claiming that the book makes its point very well. But what point exactly is it making? To figure that out, you’ll have to read the book. It’s an incredibly easy read. It’s quick. And it’s very inexpensive. I’m almost tempted to stop writing and just tell you to get it and read it! You won’t regret it, I assure you. But we live in a culture where we no longer even consider watching a movie until we’ve seen its preview, so here’s a basic synopsis of its seven brief, easy, and helpful chapters.

A Summary Of The Book

We can summarize the book and its major points as follows;

The KJV Will Always Have An Enduring Value

In the first chapter, the author points out the great enduring value that the KJV has and will have. He points out that if the Church were to abandon the KJV, it would lose much.

Much of English-speaking Christianity has sent the King James Version, too, to that part of the forest where trees fall with no one to hear them. That’s what we do with old translations. But I don’t think many people have carefully considered what will happen if we all decide to let the KJV die and another take its office. There are at least five valuable things we will lose — things that in many places we are losing and have already lost — if we give up the KJV, this common standard English Bible translation that has served us all since before the oldest family ancestor most of us know.

His list of reasons to retain the KJV is marvelous, and far more level-headed than the reasons typically given by those advocating that only the KJV ever be used. The first chapter alone is worth the price of the book for anyone who loves the KJV.

But Can The KJV Speak To The Man On The Street?

Having noted the enduring value of the KJV, he goes on to ask — Can the KJV actually attain its goal today of speaking to the man on the street? The Translators stated their purpose in the preface to the 1611 KJV: “We desire that the Scripture may speak like itself, as in the language of Canaan, that it may be understood even of the very vulgar.” They followed the intentions of William Tyndale to make the Bible understandable by the boy that drives the plough. But the question must be asked – Is the KJV understandable to the man on the street today?

Objections to the readability of the KJV are not beside the point. They are the point. We need to examine KJV English to discover whether its difficulties outweigh all the values of retaining it.

He explains that some words that were used in the KJV have today become archaic and obsolete. One might argue that such words could perhaps be looked up in a dictionary. That’s true, but if one can’t understand a book they are reading without regularly consulting a dictionary, does it really speak the vernacular language? And more to the point, the only dictionary that would fully and accurately describe the archaic moments of the KJV is the 20-volume Oxford English Dictionary, whose price tag is a bit prohibitive for most readers (not to mention that few have a spare U-haul to carry it around in). No, the 1828 Webster’s English Dictionary is not the standard dictionary of the English language, it is not the only dictionary that explains every word in the KJV, and it is not a sufficient tool (by itself) to help one in every instance know what the KJV Translators meant by their use of Elizabethan English. Ward points out, “You can’t use current English dictionaries to reliably study the KJV. You can’t even use Webster’s 1828 dictionary, which has been reprinted in recent years. You need the OED, the Oxford English Dictionary — the preeminently massive, exhaustive, authoritative, (and expensive) resource on the English language.”

False Friends

But a much greater problem than words that are in the KJV that we no longer use today are words that are in the KJV that we do still use today, but that no longer mean what they meant in 1611. Since we do know these words, we don’t know that we don’t know what they mean, and we misread the Bible as a result. “You can teach people to look up unfamiliar words, but the issue here is not words you know you don’t know; it’s words (and phrases and syntax and punctuation) you don’t know you don’t know — features of English that have changed in subtle ways rather than dropping completely out of the language.” Ward calls these words “false friends.” He notes, “The biggest problem in understanding the KJV comes from ‘false friends,’ words that are still in common use but have changed meaning in ways that modern readers are highly unlikely to recognize.” He doesn’t mean that these words themselves are false. He doesn’t think the KJV Translators were mistaken to use them. He points out repeatedly, “I’m not criticizing the brilliant KJV Translators in the least. I am not smarter than they. I presume they knew what they meant, and that their original readers did too.” These words all made perfect sense in 1611. But language changes, and the KJV Translators shouldn’t be faulted for not being prophets.

Let me provide an example (one that I didn’t see in the book, but which I think makes the book’s point well). I have many good friends who hold KJV Only or TR Only beliefs, whom I love dearly. A handful are sometimes willing to talk about the issue. Whenever I point out in such conversations that the English of the KJV is not easy to understand today, I am almost invariably told that we are not supposed to just read the Bible; we are supposed to study it. “After all,” my friends usually claim, “The Bible commands us to ‘Study to shew ourselves approved.’” They are of course invoking II Timothy 2:15, which reads in the KJV, “Study to shew thyself approved unto God, a workman that needeth not to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth (2 Tim. 2:15 KJV).” But they are at the same time demonstrating the very point they contest. Because when the KJV Translators wrote the phrase, “Study to shew thyself approved,” they didn’t mean for it to be a command to study the Bible. We see the word “study,” and think of its modern definition, “To devote time and attention to gaining knowledge of (an academic subject), especially by means of books.” But the KJV Translators didn’t have that in mind at all when they wrote what they did, and Paul didn’t have that in mind when he wrote the passage originally. Rather, the word “study” is one of those “false friends” that Ward writes about. In 1611, the word had its now archaic meaning of, “to endeavor diligently,” “make an effort to achieve,” or, “Try deliberately to do” (Shorter OED 3). The KJV Translators used this word study with its now archaic meaning to translate a Greek word that means, “To be especially conscientious in discharging an obligation, be zealous/eager, take pains, make every effort, be conscientious” (BDAG 3). What the KJV Translators meant for Paul to say in the passage was, “Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved.” Or, “Be diligent to present yourself approved to God.” These are the NIV and NKJV translations of the passage, which are saying the exact same thing that the KJV translation once said to its readers. But today, the KJV says something entirely different to a modern reader. And anyone who has ever referenced or quoted this passage as a command to study the Bible is revealing undeniably how easily the KJV miscommunicates today — through no fault of the Translators.

For example, William Grady in his book “Final Authority” has a whole chapter attacking the NKJV. He seems to suggest at points that it used a different Greek text than the KJV (or at the least, that it is an inferior translation). This is not true of course. One of his examples is this passage. He writes,“We still cannot find [in the NKJV] the command to ‘study’ God’s Word.” (pg. 311).” He seems to be making the accusation that the NKJV is part of some deliberate conspiracy to remove “the command to study God’s Word” from the Bible. In doing so, he is revealing a deep lack of knowledge not only of the Greek of the TR, but also in this case of how to understand the English of the KJV, (which he ironically claims to be easy to understand). The KJV Translators didn’t intend II Tim. 2:15 to be a command to study God’s Word. Even his use of this text as an example proves the point. He is trying to defend the KJV, but the English is archaic enough that he isn’t able even to read and understand what it says, and so he hurls false accusations at the good men who produced the NKJV. Perhaps basic Christian humility should cause us to be hesitant before throwing accusations at good and godly men like the NKJV Translators, especially if we really don’t know what we are talking about. Of course Grady should not be faulted for misunderstanding the KJV. It’s not his fault – and it’s not the KJV translator’s fault. Through no fault of theirs, the English language has changed. The KJV, at some points like this one, simply no longer represents the words “easy to be understood” that Paul so valued. Perhaps you think you are well-versed in the KJV’s language, and would never be impeded by such “false friends.” Take this quiz from Ward using just a handful of examples, and find out if you really do speak KJV.

How Readable Is The KJV?

Perhaps someone thinks, “But I’ve read that computer tests have shown that the English of the KJV is only at the 5th grade reading level?” (or 6th, or 8th, or 3rd). Claims like this occur in almost all literature defending the KJV. I’ve seen some claim that the KJV is easier English than the ESV, or even easier English than the NIV. I don’t know how someone says that kind of thing with a straight face and an honest heart, but I’ve seen them do it. So what about readability tests like the Flesch-Kincaid and others? What can they tell us about the readability of the KJV? Ward devotes a whole chapter to this question. In reading it, you will come to understand the ins-and-outs of what “readability” means, and what these tests are all about. If you have seen statistics that claim the KJV is easy reading for 5th graders, or have shared such stats yourself, this chapter will be in invaluable “inside look” at how these tests work, what they measure, and what they mean. Even if you plan to keep sharing and recommending such statistics, you should have some knowledge of what these tests are, and this chapter will fill you in.

Should The Bible Speak “Words Easy To Be Understood?”

Now, brethren, if I come unto you speaking with tongues, what shall I profit you, except I shall speak to you either by revelation, or by knowledge, or by prophesying, or by doctrine? And even things without life giving sound, whether pipe or harp, except they give a distinction in the sounds, how shall it be known what is piped or harped? For if the trumpet give an uncertain sound, who shall prepare himself to the battle? So likewise ye, except ye utter by the tongue words easy to be understood, how shall it be known what is spoken? for ye shall speak into the air. There are, it may be, so many kinds of voices in the world, and none of them is without signification. Therefore if I know not the meaning of the voice, I shall be unto him that speaketh a barbarian, and he that speaketh shall be a barbarian unto me.

– 1 Cor. 14:6-11 KJV

In the next chapter, the author makes a strong biblical case that translation should be made into the vernacular tongue – the language of the common people. Agreeing with William Tyndale, Miles Coverdale, the KJV Translators, and the authors of the NT, he makes the case that God always intended the Bible to speak the language of the man on the street, that translations of the Bible should do the same, and that the KJV, while it might have accomplished this goal in its own day, simply does not do so today. For those who respect the Bible as the Word of God, and who wish their attitude towards translations to be in line with both what God has done in history in giving His Word, and with what the Bible specifically has to say that impacts translations and their forms, this chapter may be the most important in the book.

If lots of Christians think the KJV is too hard to read, and if contemporary KJV readers can’t be expected to understand Elizabethan English because of ‘false friends’ and other difficulties, and if computers can’t come to the rescue, and if Bible translations — biblically speaking — ought to be made into the vernacular, it is indeed right to ask whether the KJV ought to be allowed to decline in use, despite the valuable things we’ll lose if 55 percent [the number of Christians who currently use the KJV per the author’s given stats] becomes 5 percent. Because the one thing that outweighs all the values of retaining the KJV as a common standard is whether people today can be expected to understand its English. We should ask, along with Glen Scorgie, ‘If a translation is published but fails to communicate, is it really a translation?’ In countless places, the KJV does not fail to communicate God’s words to modern readers; I’m eager to acknowledge this fact, because I grew up on the KJV and it was God’s tool to bring me to new life. But in countless places, it does fail — through no fault of the KJV translators or of us. It’s somewhere between Beowulf and the English of today. I therefore do not think the KJV is sufficiently readable to be relied upon as a person’s only or main translation, or as a church’s or Christian school’s only or main translation.

In the next chapter the author takes up, graciously, compassionately, skillfully, and briefly, ten objections to the claims of his book. If you disagree already (just from this review) you should probably read at least this chapter before you argue. Some will agree with all of his counters to the objections. Others will agree with some of them, but remain unconvinced by some others. But either way, if you disagree at any point, it’s worth the read.

Is There One ‘Best’ Translation?

Finally, Ward asks, “Which translation is Best?” And he ends up pointing out the deeply flawed nature of this question. He explains the dangerous tribalism that has come to surround the issue of Bible translations. Naturally, we can see this in King James Only circles, where, if you don’t use only the King James, you und up cast into outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. But we also see it when some push their one “favorite” or “best” translation, and degrade other translations in the process. Some love the literal NASB and regularly hate on the NIV. Some swear by the ESV and see all others as pretenders. He notes,

But I believe the tribalism — the belief that a group’s chosen translastion is one of many marks of its superiority over other groups — needs to stop. All Bible-loving-and-reading Christians need to learn to see the value in all good Bible translations. People who use the NIV exclusively need to also see the value of the NASB. People who use the ESV exclusively need to discover the help the NLT can provide. People who are KJV-Only need to stop seeing the translation work of godly, careful brothers and sisters in Christ — such as Doug Moo of the NIV, Wayne Grudem of the ESV, and Bill Mounce of both — as threats, and instead as gifts. The existence of multiple English Bible translations is a benefit to us all, not a justification for banner-hoisting and wagon-circling. I hate to see Bibles becoming symbols of division: ‘I am of Crossway!’ ‘I am of Zondervan!’ ‘I am of B&H!’

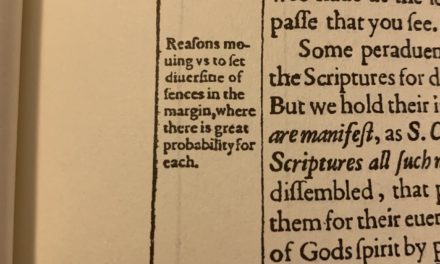

In this, he is following the KJV Translators, who were convinced that even the poorest of Protestant Bible translations should still be seen as the Word of God and respectfully treated as such. They pointed out,

Now to the latter we answer, that we do not deny, nay, we affirm and avow, that the very meanest translation of the Bible in English set forth by men of our profession (for we have seen none of theirs of the whole Bible as yet) containeth the word of God, nay, is the word of God: as the King’s speech which he uttered in Parliament, being translated into French, Dutch, Italian, and Latin, is still the King’s speech, though it be not interpreted by every translator with the like grace, nor peradventure so fitly for phrase, nor so expressly for sense, every where.

They also made the case for including alternate translations in the margins of their work (despite the King’s Rule to the contrary), because they were convinced that if one doesn’t read the original languages, then one must consult multiple translations in order to understand what the Bible is saying. Otherwise you just end up understanding the interpretation of one particular translation. You can read Ward’s excellent modern-English translation of the preface here, and his article explaining the importance of the preface for understanding the KJV translation principles here. They felt that “variety of translations is profitable for the finding out of the sense of the Scriptures.” They noted,

For as it is a fault of incredulity, to doubt of those things that are evident; so to determine of such things as the Spirit of God hath left (even in the judgment of the judicious) questionable, can be no less than presumption. Therefore as S. Augustine saith, that variety of translations is profitable for the finding out of the sense of the Scriptures: so diversity of signification and sense in the margin, where the text is not so clear, must needs do good; yea, is necessary, as we are persuaded.

The Final Word

Ward concludes then by restating his ultimate point:

What do we do with the KJV in the twenty-first century? We don’t have to throw it out; I haven’t. It’s kind of hard to get rid of memorized verses — and why would I want to? No, twenty-first century Christians should use the KJV as one of many tools for understanding God’s message to humanity. Certain famous passages — Psalm 23 and the Lord’s Prayer, perhaps — should still be taught to children. Christians searching out the sometimes thorny translation questions God has given us should check the opinions of the highly gifted KJV translators. The KJV is still useful. But it is a misuse of the KJV to ask it to do today what it did in 1611, namely, to serve as a vernacular English translation. For public preaching ministry, for evangelism, for discipleship materials, indeed for most situations outside individual study, using the KJV violates Paul’s instructions in I Corinthians 14. The value of vernacular translation is so great that we must fight to protect it — even if that means letting that trend line from 100 percent [the amount of the English-speaking population who once used the KJV] to 55 percent [the amount of the English-speaking population who currently use the KJV per the author’s given stats] continue. Even if it means helping that trend line along. We need God’s Word in our language, not in someone else’s.

My Thoughts On The Book

I’m incredibly grateful for Ward’s work. I think everyone who uses the KJV should read it. Especially if they only use the KJV, and even more so if they are of the opinion that everyone should only use the KJV. I think he makes a strong, patently biblical case for why no one should hold such a view. His book is straightforward, biblical, easy-to-read, and avoids the kind of technical discussions that such a conversation can easily evoke. And it especially avoids the kind of unchristian tone that far too often characterizes discussion of this issue.

There are a few points I slightly disagree with. First, the book seems to suggest at points that the KJV Translators produced a vernacular version that spoke to the men on the street of their day. That they intended to do so is clear by their stated intentions. That they succeeded is far from clear, and is a matter of some debate among scholars. For example, Robin Griffeth-Jones, in a collection of essays quoted elsewhere in the book, brought up reservations to such a claim, and pointed out that many see the Translators as having fallen short of their aspirations for an English Bible that spoke the vernacular. He suggests that the plan for a vernacular translation in the KJV arrived stillborn, noting that, “the KJV was oddly archaic even in 1611.” The KJV, in regards to speaking the vulgar tongue,

Had feet of clay from the very start. The translators, heirs to William Tyndale, desired ‘that the Scripture may speak like itself, as in the language of Canaan, that it may be understood even of the very vulgar’; but the archaic, clumsy KJV fell short of its own translator’s ideals even at the time, and those translators would surely be appalled at its continued use today, after four hundred years of linguistic change, as an icon of ancient and true religion. It is the principles of the KJV translators themselves, giants on the shoulders of the giant Tyndale, that speak most clearly against the church’s ongoing use of their own translation.

Others would make a similar objection, like Leland Ryken and Alister McGrath. Ward notes this objection, admits that there is some truth to the point, and responds well in his chapter answering objections. But I would have leaned towared a little more explanation of the complexity at this point. The question is a difficult one, and I’m not sure I have the answers figured out. At one point, after reading the stated aims of the Translators in the preface, and feeling the difference in register between the preface and the text of the KJV, I made the claim regularly that the KJV was written in the vernacular of the day. But a more mature examination makes me less certain, and I now lean towards the position that the opposite is the case, and that the KJV is, quite accidentally, locked into the already archaic language of Anglican liturgy, since it revised an Anglican text, incorporated the Anglican tradition, and was translated by men who were, almost without exception, ordained Anglican priests. While we can clearly affirm that the KJV Translators stated that they meant to produce a vernacular version, I’m less confident that they succeeded, and would have more directly explained the complexity of this question.

The second minor issue involves Ward’s overall approach. I couldn’t be more grateful for his work and what he has done, including the way he has done it. His choice to ignore in his book the issues of textual criticism, manuscript history, and the history of the printed text, will likely cause his work to be far more helpful than it would be otherwise. It’s a bonus for most readers. However, I myself don’t see anything wrong with engaging such issues. It might be true that most defending the KJV are not capable of discussing such issues intelligently. It probably is true in fact. But unfortunately, they are already teaching, with an amazing dogmatism, about such issues. I do wish that his call to be humble in the light of ignorance were heeded, but there are a host of individuals teaching about Greek texts and manuscripts, saying things that are nothing short of nonsense. For myself, I plan to continue to point out when they speak what amounts to nonsense, especially when they raise that nonsense to the level of doctrine, and cause division in the body of Christ over it.

Several years ago I searched out the issue myself. Learning that I had been deeply misinformed about these technical details was essential in my own journey towards leaving those views, and the groups that held them, painful as it was to do so. I had to come to understand that no careful study of the Bible could sustain the claim that it taught what I was taught about the “preservation” of the KJV. And further, I had to learn that any claim that the KJV is both perfect and preserved is ultimately dishonest. Anyone can claim the KJV to be perfect. But it cannot at the same time be both perfect and “preserved” in some unique sense, because the word “preserved” means to keep something the same; not to make it different. But the one thing the KJV did not do is keep the biblical text the same. The English text is a revision of the 1602 Bishop’s Bible. It didn’t keep the Bishop’s Bible the same – it made it different. The Greek text doesn’t translate a Greek text that always existed, evidenced in thousands of manuscripts – it created a new, eclectic Greek text that had never existed anywhere, in any language, before 1611 (and never anywhere in print until 1881). This text disagrees with literally every Greek manuscript in existence. There are not thousands of Greek NT manuscripts that contain the exact text of the KJV NT as I was taught; there’s not one. Not even close. The KJV Translators, by their text-critical decisions (to say nothing of those of Erasmus and Beza who’s work they extended) created a new form of the text that had never existed anywhere until that point. One can claim that they were inspired to create a perfect restoration of the NT, if one so chooses. That is logically consistent at least.

And this is what any position that claims the KJV, or its original language texts, to be perfect ultimately demands, however much those holding such positions may protest that this is not what they believe. No one can claim honestly that the KJV, or its original language texts, are both perfect and preserved. That simply isn’t an honest use of language.

I think such technical details are still worth explaining. I wouldn’t have realized I was wrong without them.

But both of these objections are simply things I might have done a little bit differently had I written the book. And had I written it, it would no doubt be far less helpful and successful. I am quite glad, and deeply grateful, that Ward has written it. I wish I would have read this book 15 years ago.

So I say again, if you love the KJV, if it is the only version that you use, or if you have friends who only use it, then you should read this book.

Postscript – Noah Webster On The Archaic English Of The KJV

Most who defend the KJV in some kind of unique respect hold the Webster’s 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language in very high regard. As Ward notes in his book, this is not a wise approach. The 1828 had great value in its day. But today, the gold standard of English dictionaries is the 20-volume Oxford English Dictionary. While the 1828 is often sold to deceptive claims that it is the “only” dictionary to define every word of the King James Bible, the OED of course makes its treatment look like only a gloss. Nonetheless, Webster certainly did know the English language. I point this out for an important reason. One of the most common reactions to Ward’s book has been to argue against its basic premise; to claim that the English of the KJV is not archaic, and not hard to understand; that “false friends” either don’t exists, or aren’t that big of a deal. But I suspect that every single person making such a claim would acknowledge that Noah Webster, of the 1828 fame, knew English better than they do. So what would he think? What would his opinion of the thesis of Ward’s book be? Fortunately, we do not have to guess and wonder. He actually already affirmed Ward’s basic point, (another case of someone plagiarizing Ward long before he wrote). Webster actually produced his own revision of the KJV. He wasn’t interested in changing, altering, or updating the Greek and Hebrew texts behind the KJV. But he did feel that, even in his day (almost 200 years ago!), the English of the KJV had grown archaic and difficult to understand. So he created a very light revision, which sought only to update the archaic language. In his preface, he makes the same point Ward is making. And none can gainsay his command of the English language. No one today really has the right to tell him, “Well, you don’t know what you’re talking about. You just think the KJV is hard to understand because you don’t know it as well as I do.” Or, “You just think it’s hard to understand because you don’t know English very well, and have been dumbed down by modern society.” Webster simply isn’t open to such charges. And so I quote sections from his preface here at length, which can be read free here; making Ward’s basic point from almost 200 years ago. I have italicized sections were he makes exactly the claims that Ward has made, and against which, oddly, Ward has found pushback in a way that Webster would not. Here is the opinion of Webster on the matter;

Containing the Old and New Testaments, in the Common Version, with Ammendments of the Language by Noah Webster, LL. D.

The English version of the sacred scriptures, now in general use, was first published in the year 1611, in the reign of James I. Although the translators made many alterations in the language of former versions, yet no small part of the language is the same, as that of the versions made in the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

In the present version, the language is, in general, correct and perspicuous; the genuine popular English of Saxon origin; peculiarly adapted to the subjects; and in many passages, uniting sublimity with beautiful simplicity. In my view, the general style of the version ought not to be altered.

But in the lapse of two or three centuries, changes have taken place, which, in particular passages, impair the beauty; in others, obscure the sense, of the original languages. Some words have fallen into disuse; and the signification of others, in current popular use, is not the same now as it was when they were introduced into the version. The effect of these changes, is, that some words are not understood by common readers, who have no access to commentaries, and who will always compose a great proportion of readers; while other words, being now used in a sense different from that which they had when the translation was made, present a wrong signification or false ideas. Whenever words are understood in a sense different from that which they had when introduced, and different from that of the original languages, they do not present to the reader the ‘Word of God’. This circumstance is very important, even in things not the most essential; and in essential points, mistakes may be very injurious.

In my own view of this subject, a version of the scriptures for popular use, should consist of words expressing the sense which is most common, in popular usage, so that the ‘first ideas’ suggested to the reader should be the true meaning of such words, according to the original languages. That many words in the present version, fail to do this, is certain. My principal aim is to remedy this evil…

These considerations, with the approbation of respectable men, the friends of religion and good judges of this subject, have induced me to undertake the task of revising the language of the common version of the scriptures, and of presenting to the public an edition with such amendments, as will better express the true sense of the original languages, and remove objections to particular parts of the phraseology. In performing this task, I have been careful to avoid unnecessary innovations, and to retain the general character of the style. The principal alterations are comprised in three classes [the first of which is the removal of words and phrases that “are wholly obsolete”]…

The language of the Bible has no inconsiderable influence in forming and preserving our national language. On this account, the language of the common version ought to be correct in grammatical construction, and in the use of appropriate words. This is the more important, as men who are accustomed to read the Bible with veneration, are apt to contract a predilection for its phraseology, and thus to become attached to phrases which are quaint or obsolete. This may be a real misfortune; for the use of words and phrases, when they have ceased to be a part of the living language, and appear odd or singular, impairs the purity of the language, and is apt to create a disrelish for it in those who have not, by long practice, contracted a like predilection. It may require some effort to subdue this predilection; but it may be done, and for the sake of the rising generation, it is desirable. The language of the scriptures ought to be pure, chaste, simple and perspicuous, free from any words or phrases which may excite observation by their singularity; and neither debased by vulgarisms, nor tricked out with the ornaments of affected elegance….Alterations in the popular version should not be frequent; but the changes incident to all living languages render it not merely expedient, but necessary at times to introduce such alterations as will express the true sense of the original languages, in the current language of the age…

The Bible is the chief moral cause of all that is ‘good’, and the best corrector of all that is ‘evil’, in human society; the ‘best’ book for regulating the temporal concerns of men, and the ‘only book’ that can serve as an infallible guide to future felicity. With this estimate of its value, I have attempted to render the English version more useful, by correcting a few obvious errors, and removing some obscurities, with objectionable words and phrases; and my earnest prayer is, that my labors may not be wholly unsuccessful.

– N. W., 1833.

This the third of as many pages on your web site that I’ve read, but certainly not the last.

I find your writing balanced, humble, HUMBLING even to an arrogant, condescending, sarcastic souse such as myself, informative, eye opening, and engaging.

I’ve read most, but all the books you suggested including Ward’s. I’ve Price’s book on my shelf but have two others to first finish.

If nothing else I regularly spend more time studying translations of His Word now than 6-7 years ago.

Blessings. Keep ‘em coming.

Tony Keve

We all will be judged for teaching. James 3: King James Version

1 My brethren, be not many masters, knowing that we shall receive the greater condemnation.

Read Isaiah 14:12

But, before you do read the KJV and know that this passage is talking about Lucifer and his fall. In your version, do you have the name Lucifer? And did you know if your version, it will later use Day Star 2 Peter 1:19 or Morning Star Revelation 22:16 to point to Jesus. In most of the modern versions they replace Lucifer with the name Day Star or Morning Star which are names of Jesus.

It is a big deal to change Lucifer with Jesus. The serpent was more subtil than any beast of the field in Genesis 3. Satan’s subtil changes as he says “Hath God said?” get people to question the true word of God in the KJB. Yes, I am a King James onlyist and if you look at the passage below that replaces Lucifer with names of Christ, you hopefully will be too.

Lucifer is the son of the morning, but not the Day Star (Jesus) or Morning Star (Jesus). These subtil changes twist God’s word.

King James Bible

How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning! how art thou cut down to the ground, which didst weaken the nations!

New International Version

How you have fallen from heaven, morning star, son of the dawn! You have been cast down to the earth, you who once laid low the nations!

English Standard Version

“How you are fallen from heaven, O Day Star, son of Dawn! How you are cut down to the ground, you who laid the nations low!

Berean Standard Bible

How you have fallen from heaven, O day star, son of the dawn! You have been cut down to the ground, O destroyer of nations.

New American Standard Bible

“How you have fallen from heaven, You star of the morning, son of the dawn! You have been cut down to the earth, You who defeated the nations!

NASB 1995

“How you have fallen from heaven, O star of the morning, son of the dawn! You have been cut down to the earth, You who have weakened the nations!

NASB 1977

“How you have fallen from heaven, O star of the morning, son of the dawn! You have been cut down to the earth, You who have weakened the nations!

Amplified Bible

“How you have fallen from heaven, O star of the morning [light-bringer], son of the dawn! You have been cut down to the ground, You who have weakened the nations [king of Babylon]!

Christian Standard Bible

Shining morning star, how you have fallen from the heavens! You destroyer of nations, you have been cut down to the ground.

Holman Christian Standard Bible

Shining morning star, how you have fallen from the heavens! You destroyer of nations, you have been cut down to the ground.

American Standard Version

How art thou fallen from heaven, O day-star, son of the morning! how art thou cut down to the ground, that didst lay low the nations!

Regardless what you say. The version that God prepared for the end times as he knew most of the world would be dominated by the English language is the King James. God is able to know what would be happening now.

The King James bible has a built in dictionary for hard words that are usually self-defined in the first passage they are mentioned.

Doyle,

I used to think exactly what you do about this notion. I now completely disagree. I have not yet moved my treatment of this issue from my old site to the new one here. Thanks for reminding me to do so. If you wish to read my thoughts on the matter, I have explained them at two posts at the old site. Part one here – https://bloggingtheword.com/the-blog/do-modern-versions-support-satan and pert two here – https://bloggingtheword.com/the-blog/do-modern-versions-substitute-jesus-for-satan-part-2. Blessings.

I made a post that was deleted off this site. Why? Was it because I disagreed with you and pointed out where the NIV and ESV switch the name Lucifer with the names of Jesus (Morning Star) and (Day Star) in Isaiah Twelve?

Doyle, your comment was not deleted. That’s silly. I just get mostly spam comments and so have my site settings such that I have to personally approve a comment before it appears. I don’t really want these comments full of repetitious or spammy comments. Blessings.