On Monday, 16 Jan. 1604, the King James Bible was commissioned by the royal authority of King James VI and I. Before examining that commission, I decided to explore potential precursors. In 1601 James called the Scottish General Assembly to meet in Burntisland where it commissioned a new Bible. The masterful and greatly missed historian Jenny Wormald concluded that the “origin of the Authorized Version of the Bible lay in [James’] proposal” to the Assembly (pg. 11). Numerous scholars make similar claims (e.g., David Norton, pg. 82-83; David Wright, pg. 208; William Craig, pg. 220ff). Land of birth may determine citizenship, but place of conception is not unimportant to heritage and identity. Was the KJB first conceived in Scotland or England?

Essential Background

Background against which the decision appeared is essential. On 13 March 1543, as the Reformation made its way into Scotland, Parliament allowed liberty to read the English Bible “till the prelates and kirkmen [churchmen] set forth a translation more correct.” By parliamentary act liberty was granted “to every man or woman to read the Scriptures in their own, or the English tongue,” and all contrary acts abolished (Calderwood, pg. 157). The First Book of Discipline, a reform program of the 1560 Parliament, concluded “that every Kirk [church] have the Bible in English” (pg. 184). In 1564 the Genevan Metrical Psalter appended to the Book of Common Order (STC 16577) was authorized by the Kirk, the text that formed “the structure and substance of Scottish worship until the 1640s,” as Alisdair Raffe terms it in a major Oxford Handbook (pg. 321). The Geneva Bible soon became, Ian Torrence argues in an Oxford treatment, “the distinctive biblical artifact of the Scottish Reformation” (pg. 160).

A Geneva text printed by Thomas Bassandyne in Edinburgh in 1579 carried a long dedication to James VI and his Royal Arms on the title page (STC 2125). The General Assembly funded this semi-official Bible by ordering every parish church to pay subscriptions (approved by the Scottish Privy Counsel). Parliament required every wealthy home to have a Bible and Psalm Book (Torrence, pg. 169). The dedication in the Bassandyne Bible by the General Assembly, dated 10 July 1579, connected royal authority to the work, likening James’ wisdom to that of Solomon (a sure path to his favor). I anglicize and modernize: the “setting forth and authorizing of this book chiefly pertains to your charge,” they argued (probably in Robert Pont’s voice: see below). Connecting Scottish and continental Reformation, Marian exiles who landed in Geneva “banished from their country for the Gospel’s cause,” who had “faithfully and learnedly translated this book” out of the original languages, deserved praise in “the commonwealth of them that speak our language.” James was the key player to them (though only 13 at the time and probably lacking any mature opinion as yet) for,

one great part of the honor of advancing this work pertains to you: by whose authority it was of a certain time past ordained that this holy book of God should be set forth and imprinted anew within your own realm, to the end that in every parish Kirk there should be at least one thereof kept: to be called the common book of the Kirk, as a meet ornament for such a place and and a perpetual register of the word of God, the fountain of all true doctrine….we have great occasion both to glorify the goodness of God towards this country and also highly to extol and commend your Highness’ most godly purpose and enterprise.

Printing the Bible in Scotland was difficult and expensive, but Scotland now had an approved English Bible, Psalter, common liturgy, and a king who it was hoped would back each. Not everyone was content. Scottish Reformation had not achieved “the Protestant objective of making the Bible available in the vernacular languages of the people” (Raffe, pg. 319) which marked out continental and English Reformation: a problem even worse among the Highlands, where it remained difficult, even a century after Scotland adopted the Reformation, “for ministers in Gaelic areas to communicate the contents of the Bible” (Raffe, pg. 320) due to even greater linguistic divides. We should not over-press linguistic differences (some linguists considered these different dialects). Still, most identify a distinctly Scottish language (hear beautiful examples here) important to national heritage. The Geneva Bible “was intelligible to Scots speakers” (Raffe, pg. 319) partly because preachers often adapted its language to Middle or Lowland Scots (Raffe, pg. 319; Torrence, pg. 168). The 1543 Parliament may have allowed liberty to read the Bible “in their own, or the English tongue” (Calderwood, pg. 157), but in 1601 half a century had passed, and one of those options remained unavailable.

The General Assembly and its Extant Accounts

Burntisland Parish Church, sometimes called The Kirk of the Bible, chartered 1587, site of the 1601 General Assembly, Wikimedia Commons

The General Assembly, started in 1560, initially met annually. James disliked it, understandably; it authorized his kidnapping and regularly challenged monarchy. His 1584 Black Acts determined it could meet only when called, eventually going two decades without meeting. James called the Assembly to meet in 1601 at Burntisland parish church (see images here, including the ornate pulpit, magistrate’s pew, and stalls from which Assembly members were addressed) which he had ordered built there in 1587 (see the charter at 6:51 here), sometimes known as The Kirk of the Bible. On 16 May 1601, complaint was brought to that Assembly by “sundry of the brethren” about the translation, Psalter, and prayers in the Common Order. Moderated by Robert Wilkie, this Assembly moved to revise the biblical text and Psalter but not the prayers. Plans were never carried through. Four accounts of the motion remain. Two are official records, and two contemporary Scott’s histories:

- Official Records – The Book Of The Universal Kirk (approved 1638)

- David Calderwood’s History of the Kirk (autograph 1627)

- Official Records – Acts and Proceedings of the General Assembly (approved 1838)

- John Spottiswoode’s History of Scotland (first edition 1655)

Book of the Universal Kirk

The earliest official manuscript records, The Book Of The Universal Kirk, were physically seen and approved by the General Assembly in 1638. Alexander Peterkin edited the manuscripts in 1839. I anglicize and modernize from pg. 497-98:

It being intended by sundry of the brethren that there were sundry errors that merit correction in the vulgar translation of the Bible, of the Psalms in meter, as also that there were sundry prayers in the Psalm book which would be altered, in respect they are not convenient for the meantime. In the which heads the Assembly has concluded as follows: first, concerning the translation of the Bible, that every one of the brethren who have the best knowledge in the languages employ their travails in sundry parts of the vulgar translation of the Bible that needs mended, and to confer the same together at the next Assembly. It is not thought good that the prayers already contained in the Psalm Book be altered, but if any brother would have any other prayers added which are meet for the time, ordains the same first to be tried and allowed by the Assembly.

Calderwood’s History of the Kirk

David Calderwood (1575-1650) was an opponent of episcopacy throughout his career. James disapproved and after a confrontation between them in 1617 banished him to Holland where he remained till 1625. His lasting impact was as an unparalleled historian, working for decades on a massive History of the Kirk. The General Assembly authorized an annual pension for him to finish it. The seminal form of this work is a massive cache of disorganized notes, some of which remain at the British Library here.

Out of these he prepared two versions. First is a short digest, later published in 1678 as The True History of the Church of Scotland… (Wing C279; ESTC R16833). Second is three large volumes which he considered his definitive work, completed in 1627 (the autograph remains in the British Library here), posthumously published in eight volumes by the Wodrow Society in the mid-19th century as The History of the Kirk of Scotland. The 1842 edition (pg. 124 here) differs only slightly from the 1678 (pg. 456 here), modernized here:

In the last Session, it was meaned [intended] by sundry of the Brethren, that there were sundry errors in the vulgar translation of the Bible, and of the Psalms in meter, which required correcting; as also that there were sundry prayers in the Psalm Book, that were not convenient for the time. It was therefore concluded, that for the translation of the Bible, every one of the brethren, who had greatest skill in the languages, employ their travails, in sundry parts of the vulgar translation of the Bible, which need to be amended, and to confer the same together at the next Assembly. As for the translation of the Psalms in meter, it was ordained, that the same be revised by Mr. Robert Pont, and that his travails be revised at the next Assembly. It was thought good, that the Prayers already contained in the Psalm Book be not altered nor deleted; but if any brother would have any other prayers, meet for the time, added, let the same be first tried and allowed by the Assembly.

For the Metrical Psalms it was decided “that the same be revised” by Robert Pont (1524-1606) and that “his travails be revised at the next Assembly,” a historically likely element not mentioned in The Book Of The Universal Kirk. Pont was a central figure of the Assembly and occasionally a commissioner (as the following year) or moderator. He worked on a collection of Psalms (published 1565), helped craft the Assembly’s Second Book of Discipline, translated for it the Helvetic Confession, protested the Black Acts, and crafted preliminary material (probably the calendar and preface) for the very 1579 Bassandyne Bible under critique.

The Assembly “decided to begin a correction of the Geneva bible that had been traditionally used in Scotland,” but these plans, Jacobean scholar James Doelman argues, “were diverted by James’ accession in 1603” (pg. 14-15 here). In fact, the accession may not have been the initial cause of neglect. The next Assembly in Nov. 1602 had been charged to reassess the commission and examine revisions by Robert Pont. They passed both in silence, busy responding to Cardinal Bellarmine and establishing visitation articles for local kirks. Pont asked at that meeting to be relieved of his more pressing teaching duties, and the Assembly consented on account of “his great age, and long travails in the Kirk of God” (pg. 1001). If the revision plan was closely tied to Pont, then his disengagement likely halted efforts. The plan breathed its final breath with his in 1606.

Acts and Proceedings of the General Assembly of the Kirk of Scotland

A second official record of the Assembly, the Acts and Proceedings of the General Assembly of the Kirk of Scotland, supplemented the The Book of the Universal Kirk with history specific to General Assembly meetings. Edited by president Thomas Thompson and approved in 1838, the third volume records the meeting, combining elements of the earlier official record and Calderwood’s History (see pg. 970-71 here). Numerous forms of these Acts and Proceedings exist, all containing the same account. As it adds nothing material to the two above, I refer readers to the hyperlink.

Spottiswoode’s History of the Church

John Spottiswoode (1565–1639), made minister of Calder in 1583, was initially sympathetic to Scottish presbyterianism but became a fawning supporter of James VI and prelacy, following him to England for his accession in 1603. James supplied him a Scottish Privy Council seat (1605) and the influential Archbishopric of St. Andrewes (1615). A popular historian, he wrote a history of Scotland’s Kirk, published posthumously in 1655 as The History of the Church of Scotland… (ESTC R17108). I lightly update the 1655 edition (pg. 465 here; an 1847 edition is on pg. 98ff here):

After this a proposition was made for a new translation of the Bible, and the correcting of the Psalms in meter. His Majesty did urge it earnestly, and with many reasons did persuade the undertaking of the work, showing the necessity and the profit of it, and what a glory the performing thereof should bring to this Church. Speaking of the necessity, he did mention sundry escapes [blunders or printing errors] in the common Translation, and made it seen that he was no less conversant in the Scriptures, than they whose profession it was; and when he came to speak of the Psalms, did recite whole verses of the same, showing both the faults of the meter and the discrepance from the text. It was the joy of all that were present to hear it, and bred not little admiration in the whole Assembly, who approving the motion did recommend the translation to such of the brethren as were most skilled in the languages, and revising of the Psalms particularly to Mr. Robert Pont. But nothing was done in the one or the other. Yet did not the King let this his intention fall to the ground, but after his happy coming to the crown of England set the most learned Divines of that Church a-work for the translation of the Bible, which, with great pains and the singular profit of the Church they perfected. The revising of the Psalms he made his own labor, and at such hours as he might spare from the public cares went through a number of them, commending the rest to a faithful and learned servant, who hath therein answered his Majesty’s expectation.

Spottiswoode skims through the request and motion in a single sentence. He then paints a king astounding all present by his scriptural knowledge, equaling professional clergy (that tracks: James loved to impress), and urging this project “earnestly” and offering “many reasons” why it was necessary, profitable, and glorious. James enumerates errors in “the common translation” and recites whole verses of the Psalter, demonstrating complex errors of meter and text extemporaneously. This Solomonic figure elicits “joy” and “admiration” from the whole assembly, then burns the night oil, personally working on the Psalms “at such hours as he might spare from the public cares.” His intention doesn’t “fall to the ground” (language intentionally evoking OT prophetic certainty; 1 Samuel 3:19, etc.), but he steadfastly persists until the KJB is produced, which, to “the singular profit of the church,” his scholars perfect.

The flattery is thick enough to cut with a knife, raising suspicions about the account. Spottiswoode was mostly in France, not Scotland, from 1601-1603, serving as chaplain to the Duke of Lennox, and likely not present for these events. Only his account paints such a fawning picture of James at the meeting. Indeed, only Spottiswoode mentions any involvement by James at all. Only he connects the decision to the KJB, making his account contradictory. If “nothing was done” with either complaint, he is wrong to connect them to the KJB or the work of James on the Psalter; if he is right in these connections, he is wrong that “nothing was done.” The contradiction likely stems from a poor copy-paste; Spottiswoode has not built from scratch. If he held in his hands a 1611 KJB, knowledge that James worked on a Psalter or a copy of the 1631 Psalms of David (STC 2732), record of the meeting, and his own penchant for Jacobean flattery – such inventory would provide all the building blocks needed to conjecture precisely this account. The specific involvement of James could be accurate, though mentioned nowhere else; the details border on hagiography.

The Scottish Psalter of James VI and I

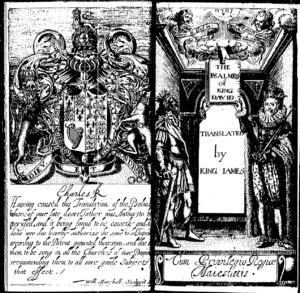

The 1631/6 Psalms of David, Translated by King James (STC 2732) became a flash point of controversy in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Doelman traces their reception history (pg. 454-475 here; pg. 135-157 here). Charles I always maintained they were the work of James VI and I, promoting them as such. Contemporaries accepted this; scholars today doubt it. Most think them largely the work of Sir William Alexander (pg. 454). Whatever authorship is determined, James had interest in the Psalter before and after 1601. In 1584 he versified Psalm 104, probably his earliest translation work (STC 14373; pg. 70ff here).

James noted in 1591 (STC 14379) that good reception would hasten production of his paraphrase of Revelation and “such number of the Psalms as I have perfected: and encourage me to the ending out of the rest.” MS Bodl. 165, fol. 58b contains a translation by James of Psalm 101 written before 1603, transcribed by Rait (pg. 53ff), who notes that its “language is Scots” while the 1631 edition “is written in English.” BL Old Royal MS 18B. XVI contains Scottish translations of Psalms 1-7, 9-21, 29, 47, 100, 125, 128, 133, 148 and 150 with the signature J[acobus] D[ominus] R[ex] S[cotia], many in the hand of James. Joseph Mead noted in a 23 April 1625 letter that James had completed fifty (pg. 11-2). Doelman concludes James completed at least 28 Psalms in Scotland which are “completely different” from those published under his name in 1631/6 (pg. 136).

McMillan’s unsurpassed study of the Psalms of James (Vol. 1; Vol. 2) reveals that in the manuscripts from James “the Scottish dialect is plainly marked” (pg. 114), while in the published Psalter, Scots words “have been carefully excluded.” James’ nicht, richt, delicht, upricht, glaid, caffe, lowe (flame), syne (then), and indwellaris all disappear. He concludes the contemporary Psalter “might have had more of a Scottish savor if the British Solomon’s part in it had been greater” (pg. 120). An appendix below provides examples of James’ work. In his eulogy for James, the bishop of Lincoln claimed the project consumed him to his dying breath.

This translation he was in hand with, when God called him to sing Psalms with the angels. He intended to have finished and dedicated it to the only saint of his devotion – the Church of Great Britain and that of Ireland. This work was stayed in the one and thirty Psalm, Blessed is he whose unrighteousness is forgiven, and whose sin is covered.

Spottiswoode crowned Charles I at Holyrood in 1633. Charles elevated him to the position of Lord Chancellor in 1635, part of his ill-fated campaign to force episcopacy and English liturgy, including its Psalter, onto Scotland. His attribution of the 1631 Psalms to his father played a large role in that campaign. Doelman concludes that the “idea of them, rather than their substance, had the larger effect,” and that ironically, “in the 1630s they became the most public and controversial of his works, at a time when his other works faded into the background” (pg. 147).

It is hard to escape the suspicion that Spottiswoode exaggerates James’ involvement in the proposed Burntisland Bible as a piece of Stewart propaganda for Charles I. He was sometimes accused of rewriting history to favor royalism and episcopacy (pg. 107 here). The General Assembly in Glasgow on 4 Dec. 1638 deposed and excommunicated him as a “pretended archbishop” (pg. 14 here). Notably, the General Assembly never added his anecdotes about James and the Burntisland Bible to any of the official records. Perhaps they too were suspicious. We should not ignore the possibility that redaction went the other way: Spottiswoode could present genuine history which a Presbyterian and then parliamentarian impulse decided to remove James from in official sources, just as it might have cut the monarchy out of Scotland altogether. Spottiswoode and Calderwood did occasionally go toe to toe. Though remotely possible, this is unlikely. Norton cites only Spottiswoode when presenting the decision (which he mistakenly dates to 1602) as a direct precursor to the KJB (pg. 82-83), as does Wormald (pg. 11), revealing how easily reliance on a single, later, biased source might mislead even the best of scholars.

Connecting Burntisland to the KJB

The Bible envisioned by the 1601 General Assembly of Burntisland was a Scottish revision of the Geneva Bible; the KJB was an English revision of the 1602 Bishops’ Bible, as Rule 1 demanded (see BL MS Harley 750, fol. 1v, pg. 88 here). The Burntisland Bible would have been in Lowland Scots, like the work of James on the Psalter (the complaint may even have been spurred by lack of a Scottish Bible); the KJB was in the liturgical language of England. Nothing like the “& uith á bouddenit brest dois seame to bold” (see appendix below) of James could have entered the KJB or English liturgy. The Burntisland Bible was commissioned by the General Assembly for approval in the Scottish Kirk; the KJB was commissioned by royal authority as the Bible for public liturgical service in England. The Burntisland Bible disappeared into oblivion; the KJB was carried through an elaborate process to completion. Indeed, the defining feature of Burntisland’s Bible – appropriation of Geneva into Scottish Reformation – was precisely the element James rejected at Hampton Court, declaring the Geneva “the worst of all” Bibles (Barlow pg. 47). Rejection of its copious notes, in turn, was ordered to be the defining feature of the KJB “without any notes.”

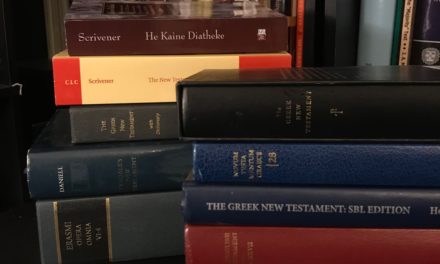

Record of Hampton Court decision to print a new Bible, “and that without any notes,” British Library Cotton MS Cleopatra F II, folio 120r. Click thumbnail to enter British Library Digital viewer.

Burntisland’s Bible was not a direct precursor to Hampton Court. Virtually nothing but the presence of James himself connects the two. Jacobean biographer Pauline Croft wisely concludes, in a lecture that first got me thinking about this question, “although many historians have emphasized Burntisland as the origins of the KJV, I think it’s a bit more complicated than that. There is no straight lineal descent” (5:07 here). Ken Fincham, relying on Spottiswoode, cautiously sees Burntisland revealing a James “much invested in biblical translation” (pg. 79 here), explaining his eagerness to assent at Hampton Court, the same cautious connection made by Mordechai Feingold (pg. 1). However, this interest in translation was evidenced long before, after, and apart from Burntisland, in the neglected work of James on the Psalms, his paraphrase of Revelation, and other biblical writings. Burtisland might in fact be evidence of precisely the opposite of such a connection. Raffe suggests (pg. 321 here) that the 1601 Assembly left a bad taste in the mouth of James, which could explain why he “was reluctant simply to impose the [KJB] on the Scottish Church.” Later, “the canons promoted by his more authoritarian son, Charles I, were swept away in the Covenanting revolution.” The result was that the

King James Bible was ‘authorised’ in the Church of Scotland for less than three years. In the 1640s, Dutch-printed Geneva Bibles, which in contrast to English editions lacked the Apocrypha, continued to be imported to Scotland. This did not prevent the King James Bible from gradually superseding its predecessor. But some evidence suggests that Presbyterians were critical of the King James translation. As late as 1695, a minister censured the approach of the translators, ‘alledging that they were a company of men set to please King James’. Unsurprisingly, one of his objections was to the frequent use of the word ‘bishop’, which the minister saw as a deliberate strategy ‘to countenance Episcopacy’.

If Burntisland’s Bible is not a direct precursor to the 1611 KJB, what of other potential precursors? In our next post I take up a second alleged precursor: an undated parliamentary bill calling for a new translation.

Appendix – Psalms from James VI and I

Psalm 133

Taken from BL Old Royal MS 18B. XVI, transcribed by McMillan, pg. 118:

How goode and pleasant thing lo doth appeare,

Accorde amongst thaimeselfis of brethren deare,

Quho dwell together in a godlie love;

It is most like that precious unguent deare,

poured on the heade, syne trikling like a teare,

upon the beard down flowing from above.

At last doun Aaron’s clothis doth softlie move,

quhill to his garments borders low it veare,

and round about thaime runne for his behove

like crystall dew, distilled on Hermon tall,

or balmy drops that does on Sion fall:

for on those men God sends his blessing sure,

the which is life forever to endure.Finis.

Psalm 101

Taken from MS Bodl. 165, fol. 58b, transcribed by Rait, pg. 54-55:

Thy mercy uill I sing & iustice eik,

uith musik uill I prayse Iehoua great,

I uill tak head the richteous path to seik

quhill tyme Thou call me to Thy mercie seat.

still shall I ualke in uprichtnes of soule

uithin my house quhich halloued is to The,

myne eyes upon no uikkid thing shall roule,

for all suche deides I hate & shall thaime flee.All godles men (thay shall) from me depairt,

I uill not knou no euill nor uikked thing,

the toung bakbytes the nichbour in quyet pairt

I uill cutt out & lett it for to spring,

the man that lookis to hie throuch suelling pride,

& uith á bouddenit brest dois seame to bold,

him can I no uayes suffer nor abyde,

sith that myne eies true men on earth beholde.Thay shall sitt doun uith me, as also thay

shall be my seruandis that do ualk aricht,

no craftie man shall duell uith me I say

nor liers shall be stablisht in my sicht,

I uill rut out ilk morning one & all

of uikkid men that on the earth do duell,

and by that meanes lehouas cittie shall

be uoyde of uikked uorkers fals & fell.

Well-written, informative. Thank you.