James VI of Scotland, who would be forever remembered for the King James Bible, never knew anything but the life of a king, having been crowned shortly after his first birthday in 1567. But Scotland was a kingdom with little power and even less money. When Elizabeth I of England and Ireland died around 3:00 am, Thursday, 24 March 1603, his long and nervous wait for more was finally over.

While official word would not reach him till almost a week later, the secret mission of Robert Carey to inform him brought him assurance of his succession by Saturday. As Teems explains, they had long before worked out a code by which Carey would return to James a blue sapphire ring he had given to Carey’s sister if and when he was to become king. Carey brought the ring with him, and James upon seeing it knew his dreams had come true. He had been proclaimed, “James I, King of England, France, and Ireland, Defender of the Faith.”

Soon preparation began for the procession to London for his coronation; but not too soon of course. It would be bad form and quite tacky to arrive before Elizabeth’s funeral. He didn’t want to appear eager. Or rather, he didn’t want his eagerness to show. Robert Cecil had after all been coaching him via secret correspondence on how to successfully succeed Elizabeth for several years now.

On 25 July 1603, he was crowned King of England at Westminster Abbey, uniting the long-warring kingdoms of Scotland and England for the first time in their history. You can read his acceptance oath in full here. Thomas Tomkins wrote his Be Strong and of a Good Courage to be sung for the coronation, offering a prayer for the monarch derived from Deuteronomy and Joshua. You can listen here. The union of the crowns in a single monarch was a momentous event, even if attendance was curtailed because of the spread of the plague. “It is an historical irony” Jenny Wormald noted (pg. 208-209):

that the two kingdoms were brought together under a Scottish king. It is an even bigger irony that the Scottishness which created so many difficulties should also have had so much to offer the English; for by trying to transmit his Scottish style of kingship to the English throne he defused problems within the church and the state, and thereby presided over a kingdom probably more stable than his predecessor had left, and certainly than his successor was to rule.

Inheriting An England Of Contested Identity

As Diarmaid MacCulloch noted, “When James finally inherited the English throne with remarkably little trouble in 1603, he also inherited a Church of England which had… undergone a contest for its identity.” Of course, outside the official Church but still part of the package deal he inherited in the country, Catholics had long suffered severe persecution in England. Whatever hopes they had of favor from James (and he had likely made them many promises), they were sadly disappointed. Extremist discontent from the fringes soon came to the fore in the famous Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

Within the official Church we might broadly speak of the “Protestants” (a more historically accurate term would be “evangelicals”) that then made up the Church of England. But this was not quite a monolithic group, and factions within it had different attitudes towards what we now refer to as the Elizabethan Settlement. To chart out these factions, and to understand the dreams in the air at the coming of James I, we need first to understand that Settlement and the history that led to it, which means stepping back in time a little further, to the official beginnings of Reformation in England.

English Reformation?

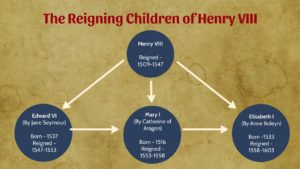

Technically speaking, Reformation in England began when Henry VIII failed to obtain papal right to divorce (annul his marriage to) Catherine of Aragon (his brother’s widow), whose only living child had been little Mary. She had given the King no male heir to take the throne. Henry had become convinced this was God’s judgment upon an illegal marriage, and it probably helped fuel his ambition that he was in love with and wished to marry the younger Anne Boleyn (who was soon enough pregnant with his daughter Elizabeth). Through a long and complex series of legal maneuvers and Acts of Parliament, Henry rejected papal authority and, essentially, replaced the Pope in England when he was then declared the Supreme Head of the Church of England.

Reformation on the Continent was born out of theology, with a burning conviction about the authority of Scripture and justification by faith at its center. Reformation in England was born, initially at least, out of politics, with a King’s ambitions and burning desire to take a new wife at its center. At that time, in most (not all) other ways, Henry was still a Catholic at heart, who had well earned his title from Pope Leo as, “Defender of the Faith,” for his firm writing against Martin Luther.

The ambiguities and complications stemming from this halting first step meant that more than anywhere else in the world, Reformation in England moved slowly, uncertainly, and by fits and starts. Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell were main drivers along this path of Reformation (as was Anne Boleyn, until Henry tired of her after their brief three year marriage, and had her beheaded for adultery), along which Henry made vacillating progress . But when his nine-year-old son Edward VI was thrust upon the throne upon his death, movement accelerated. One way to observe the progress is to trace the history of a very important book.

The Book Of Common Prayer

The subtle changes to (and brief revocation of) the Book Of Common Prayer serve as a window into the highly technical religious changes of the roller-coaster of English Reformation. The First English Book Of Common Prayer created by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, who had freedom under Edward VI to implement more of his program of reform, had been designed to replace the highly complex Latin liturgy (patterns of public worship service) of the medieval Western Church, and to severely strip down its ritual. The old liturgy required a number of different books to help the clergy know who was to do what, when. Cranmer’s vision was to reform these patterns into a form more consistent with Protestant principles, in the vernacular tongue. An early step in this program was the 1549 Book Of Common Prayer.

Makeup Of The Book Of Common Prayer

But what was a book of “Common Prayer?” To the uninitiated, a “Prayer Book” might sound like a sort of private devotional guide; a precursor to works like Charles Spurgeon’s “Morning and Evening.” (I imagined as much before I purchased my first copy.) The reality is almost precisely the opposite. The Prayer Book was a prescription for the very public liturgy of the Church, and specifically for the clergy, to help them perform various rituals according to its patterns (it was not really intended for the layman to read, though it would pervasively shape everything they would do in worship). It was, “a corpus of gestures, practices, and performances.” It could more profitably be compared to a script for a screenplay, directing what everyone was to do, and when, during the drama that was public worship.

This “script” was shaped seasonally around the liturgical calendar, one part of which celebrated the lives of the Saints with various holidays and feast, the other part of which celebrated the life and passion of Christ (with feasts like Lent to observe his 40-day fast in the wilderness). Its prescriptions shaped the forms of worship under two broad types. First were those that shaped the daily worship in the Church, giving the priest the exact words to say and gestures to make for services like the all-important eucharist. Or scripting out the exact prayers to use (known as “collects“), and the Scripture passages to be read publicly, for each Sunday and for the daily office (now reduced from the nine “hours” of the medieval divine office to just two; Morning and Evening Prayer, or Matins and Evensong), which became the very staple of daily English worship.

Second were prescriptions for occasional services, like the form for infant baptism (with the rituals for making the sign of the cross on the baby’s forehead, dipping him thrice or pouring water over him if weak, putting the white robe or chrisom on him, anointing him with oil, and blessing the baptismal water, along with exorcism), confirmation, weddings, funerals, and the like. It thus scripted the whole of life as worship of God, from brith to death. “More than a book of devotion, then, this is a book to live, love, and die to” (Cummings, pg. xii). The impact of the Book in its various editions was so profound that MacCulloch can write that from its birth to 1800, “It was the literary text most thoroughly known by most people in [England], and one should include the Bible among its lesser rivals.”

Reception Of The Book Of Common Prayer

How was it received? The first 1549 edition under Edward VI, clearly Protestant, pleased no one. Traditionalists were aghast at the newfangled changes to centuries-old patterns of worship. They rose up in various violent “prayer book rebellions,” and were slaughtered by an administration under Edward who would have nothing but its new faith allowed. Thousands were put down, “slain like beasts,” for refusing to conform to the new patterns of religion, an action which was tantamount to treason against the King (Marshall, pg. 328-355). On the other hand, those who shared the passion for reform were disturbed that the liturgy still retained so much of its Catholic ceremony and left a great many controversial points of contention ambiguous. Cranmer himself wasn’t pleased; the first 1549 edition that some perceived as a giant leap in the wrong direction was likely intended by its author as only a first step towards a much more thorough-going reform.

“For all this, the new liturgy did not look, or feel, like the services of worship that replaced the mass in Strassburg, Zürich or Geneva. The priest still wore traditional vestments (though for communion, the cloak-like cope was recommended, rather than the poncho-like chasuble), candles were placed upon the altar, and there was a hint at least of prayer for the dead in the communion service’s petition to grant mercy to ‘thy servants which are departed’, and – an echo of the requiem mass – in provision for ‘celebration of the holy communion when there is a burial of the dead’.

– Marshall, Peter. Heretics and Believers: A History of the English Reformation. Yale University Press, pg. 325.

The Second Edwardian Prayer Book of 1552 – Internet Archive.

Further movement began to take shape in Cranmer’s second, 1552 edition. Here was a much more radically Protestant book, a “total revamp,” which came much closer to reflecting Cranmer’s envisioned end-point (though probably not all the way – Cranmer still saw it as just one more step, several more of which would have been yet to come). The communion service was drastically rewritten. One no longer needed to bow to the host – the consecrated bread – at Communion, and the new “Black Rubric” now made it crystal clear that the host could not be seen as being worshipped, under any interpretation, a point whose ambiguity in the 1559 Book was variously exploited to different ends. The various ceremonies at baptism were all but gone (with the exception of the sign of the cross, which, controversially, remained). The lingering ghost of prayers for the dead had been finally sent on its way. “It was this second Book Of Common Prayer, even more than the first, which attempted to eradicate Catholic England for good” (Cummings, pg. xxxii). The effect was as though someone had slammed their foot on the gas pedal in a vehicle already rolling slowly down the hill of reform. One would expect to reach the bottom of the hill rather quickly. Instead, quite cataclysmically, it hit a brick wall and ended in a violent wreck.

Edward VI (then only 15) died after just a 6 year reign, and the reformers who were moving their program forward with his blessing suddenly found themselves ruled by his staunchly Catholic older sister (after a failed attempt to prevent it by installing Lady Jane Grey, who reigned just nine days). Her convictions against the new faith were probably strengthened by the reality that Protestant faith had declared her mother’s marriage void, and her a bastard, raising serious questions about her own royal rights. Catholic faith rendered her the rightful heir and her two younger siblings something, well, lesser. The Prayer Book was immediately revoked, the traditional Latin rite returned, and England was Catholic again, (though various Catholic “reforms” were underway, operated within a traditional framework, see Ryrie, pg. 1-15).

The Elizabethan Settlement

1590 Portrait of Elizabeth I of England, Nicholas Hilliard, located now at the Dining Hall of Jesus College, Oxford.

After decades of jolting back and forth, under Henry VIII’s changing whims, Edward VI’s passionate and speedy program of reform, and Mary I’s violent reversal of it, the only constant in English religion for the last three decades had been change. When Mary died and her sister Elizabeth I took the throne in 1558, Protestant reform began again, but of a quite different nature. Elizabeth at the start of her reign froze all the movement with what has come to be called the Elizabethan Settlement.

Acts Of Parliament

The Settlement essentially consisted of two Acts of Parliament. First was the Act of Supremacy which established the Queen as “the only supreme governor of this realm, and of all her highness’s dominions and countries, as well in all spiritual and ecclesiastical things or causes as temporal.” This granted the monarch absolute power over the Church, restoring the Edwardian system that had been revoked under Mary, though Elizabeth wisely styled herself “Governor” rather than “Head” as her father had done (perhaps sensitive to hesitation about a monarch as “Head” of the Church, and a woman at that; a title reserved for Christ in the Bible).

Second was the Act of Uniformity, which established a newly amended 1559 Book Of Common Prayer as the required liturgy of rites and ceremonies in the Church of England; a drastic change from the Catholic reign of her sister, “Bloody Mary” (1553-1558), but not quite the rapidly reforming reign of her brother, Edward VI (1547-1553). Coming with all this was the establishment of the new Articles Of Religion (amending the older Articles), the closest thing that the Church of England would ever have to a consistent doctrinal statement.

A New Prayer Book

What was so radical (or confusing) about the new Prayer Book was, first, that it was decidedly Protestant, starkly reversing Mary’s Catholic Church, but second, that it was frozen in place. Rather than simply reinstate the 1552 Book that had finally been moving reform forward at a faster pace, or take the opportunity of the new liberty to press forward with further reform, Elizabeth’s Book took the 1552 as a base, and froze it in time. Indeed, it even sent a glance backwards towards the 1549 Prayer Book that had only been intended as a stop-gap. The crystal-clear “Black Rubric” was removed, and a reference to the real presence was restored. There was still a heavy dose of the ceremonialism that reformers had been intending to abolish as “popish.”

A New Battleground

Ceremony, and how much of it (if any) there should be, became the new battleground of controversy in the Church. The Elizabethan Church was the only reformed Church in the world to still have an elaborate episcopacy of bishops over priests and deacons, retaining the medieval three-fold order. These bishops still each held a throne in their massive and elaborate cathedrals. There was still a sharply ceremonial liturgical year, and there was still heavy ritual surrounding the daily life and occasional services of the Church. Its minsters still wore (reduced, but still present) clerical vestments (special clothing for officiants at liturgical services) of sorts, a stark reminder of the medieval Church.

The Act of Uniformity imposed severe penalties for ministers failing to subscribe to the Book Of Common Prayer and the Articles of Faith, and required the clergy to wear the vestments of the second year of Edward’s reign (whatever that might have meant). Clerical vestments were a sore point among Puritans for some time in the Church, especially in the Vestiarian Controversy. Questions of what should be worn, when, and by whom, reasserted themselves controversially for years to come. The issue at hand wasn’t so much about clothing, as about what its continuing use, and the Monarchy’s claiming of the prerogative to regulate it, could be argued to represent. Clerical dress, MacCulloch explains, “might seem trivial until one realizes the symbolism involved: separate dress for the clergy in both worship and everyday life implied a continuing doctrine of a separately ordained priestly order within the reformed congregation of God’s people, a notion which cast uncomfortable spotlights over the other, more profound imperfections of Elizabethan Reformation.”

The Settlement thus granted a uniform structure to the Church of England’s worship; a uniformity that remained highly controversial throughout Elizabeth’s reign, and that effectively stalled the violent roller-coaster of change that had afflicted England for three decades. But for many, it was halting what should have kept moving. The 1552 Prayer Book was only meant to be one more step, and the new Prayer Book should have been a further step, with yet more steps to come. “Reformation” Peter Marshall notes, “was a journey; a continual striving after elusive perfection, in the world and in oneself.” Thus, for some, “The latest measures of 1559 were a staging-post, not a final destination.” But, “the Reformation, Queen Elizabeth believed, was over.” In some minds, Reform had stalled out, just as it was free to reach the bottom of the hill, and those who could see their goal through the windshield were frustrated that Elizabeth seemed to have hit the brakes. Indeed, she could be said to have thrown the car into park, and to have demanded that no one get out to walk anywhere.

In the last decade before James took the throne, discontent quieted down. Not because it had gone away, but because it was clear that Elizabeth would allow no further change in her Church, which some complained was still, “but half-way reformed,” and which it must be acknowledged still, “remained haunted by its Catholic past.”

The Factions At The Coming Of James

Division in the Church Of England was thus, when James I took the throne, expressed in a variety of attitudes towards the Settlement. Giving appropriate names or identifiers to these groups, let alone a full taxonomy, proves almost impossible. But the tensions need to be described to understand the uncertainty in the air at the accession of James; a King who hailed from Scotland no less, the long-time enemy of England (a divide just beginning to be healed), where presbyterianism had made such inroads. Would James bring the same to England? Would episcopacy itself be abolished?

Conformists

On one side of the divide were various levels of what we might broadly call “conformists,” who were pleased with the Settlement and the status of Reformation in England, and demanded that all “conform” to it. Those who would soon take the Church in its later “Anglican” direction, which some have termed “avant-grade conformists,” like Lancelot Andrewes (who would head the First Westminster Company that translated Genesis-II Kings in the KJB), stood to lose everything if the Settlement was questioned, while others simply preferred the current status quo by default. Richard Bancroft, (later to be the ultimate architect of the King James Bible) Bishop of London, whom Collinson calls “the arch Anti-Puritan,” was the doyen among the anti-Puritan conformists.

A Spectrum Of The Discontented

On the other side were diverse groups that have all-too-uniformly been classified as “Puritan,” perhaps better termed, “a spectrum of the discontented.” They had become a bit settled by 1600, but the accession of a new King stirred up tensions and revived hopes of change. These “non-conformists” (not wanting to “conform” to the current Settlement) were of diverse shades. Some were moderate, still loyal to the monarchy, but convinced that the Settlement had stopped short of the further reformation that was needed. England, to them, must recognize its King, but its King must recognize that the Church was still too close to Rome.

Others were less moderate. Some were presbyterian in persuasion. Like the exiles to Geneva, they were convinced of the wrongs of episcopacy and that the only true “biblical” model was a church structure that would abolish the bishops, (and thus severely strip the monarchy of its power over the Church). They had their hopes that England would go as Scotland had. After all, a Scottish King was taking the throne. They would be sorely disappointed to realize that James had no affinities for presbyterianism (or anything else that threatened his power and Divine Right). “No bishop, no King,” he declared on more than one occasion. Other groups, more radical still, were separatists, who would just as soon abolish the monarchy’s place altogether, and start over with a new church from the ground up. These would later become the Pilgrims to whom North America owes so much.

All of these diverse attitudes towards the Elizabethan Settlement were present when James acceded to the throne. The coming of a new King meant the reigniting of old hopes.

Dreams Of Change

Everyone was hoping that the new King would be favorable to their particular vision for the Church. The forty-five year status quo of the Elizabethan reign now appeared to be finally up for grabs. Everyone wanted to be the first to catch the new King’s ear and gain his approval for their vision. As Trevelyan put it in his vivid prose, “In the grey hours of morning, [at the death of the Queen], watch and ward was kept in London streets; and in all the neighboring counties men who had much at stake in time of crisis dreamed uncertainly of the thousand changes that day might bring.” Our non-conformists in the Church of England were no different, and a group of representatives sought the King’s attention immediately, with what has come to be called the Millenary Petition.

To the text, impact, and specific requests of this Millenary Petition, our next few posts will turn.

Posts On The Millenary Petition

- The Coming Of King James And The Millenary Petition

- The Text Of The Millenary Petition

- The Creation And Impact Of The Millenary Petition

- The Structure And Requests Of The Millenary Petition

Comments