In our last post we traced the activities of the first day of the Hampton Court Conference. In this post we overview the events of the second day, on which a new translation was first proposed. In the next we will overview the third day.

Hampton Court Day Two – Monday, 16 January 1604

On Monday, the Puritans finally got their long awaited audience with the king. Archbishop Whitgift and the other bishops had been charged to settle by Wednesday the issues commissioned to them by the king. They thus met in a separate Council Chamber while the king heard Puritan complaints. Whitgift sent two bishops as delegates representing conformity to the Puritan meeting with the king in the Privy Chamber: Richard Bancroft and Thomas Bilson. Both would go on to shape the KJB.

When the Puritan spokesmen were called in sometime between 11:00 and noon they found the men (minus the deans and doctors) already discussing matters among themselves. The deans and doctors joined them. Young prince Henry was sitting on a stool to the side, a month before his tenth birthday, probably quite bored by the events he was supposed to be observing. The king’s special chair was placed centrally as before, and when he entered, the day officially began.

James made a brief speech, determining “not to innovate the government presently established,” which had been blessed by God for forty-five years, so that “no Church upon the face of the earth more flourished” than England’s (Barlow pg. 22). He dictated his three purposes for the conference to the Puritans:

- To settle a uniform order through the whole church

- To plant unity for the suppressing of Papists and enemies to Religion

- To amend abuse

James explained that “many grievous complaints” had come since his accession and he was ready to hear from them “what they could object or say” (Barlow pg. 22-23). The Puritans set the rest of the agenda for the day.

The Puritan Spokesmen and their Complaints

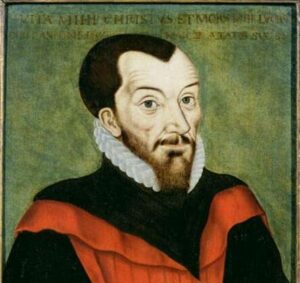

John Rainolds (1549-1607) ©Corpus Christi College, Oxford, UK. Wikimedia Commons.

The four men who had been chosen were Dr. John Rainolds, President of Corpus Christi College, Oxford; Laurance Chadderton, Master of Emmanuel College, Cambridge; John Knewstubs, Rector of Cockfield, Suffolk; and Dr. Thomas Sparke, Rector of Bletchley, Buckinghamshire. James had sent for those who he thought to be “the most…modest of the aggrieved” (pg. 22-23) as opposed to the more radical Puritan spirits. Who precisely chose them, how, and why, remain debated questions. They likely were chosen for being so moderate as to barely represent Puritan interests. They posed no substantive challenge to conformity. “Spokesmen,” we noted before, is a more accurate term than “delegates” or “representatives.” Puritans of the hotter sort (Henry Jacobs most vocally) later claimed they weren’t represented at the conference. In any case, Rainolds served as their voice. He laid out a four point agenda (Barlow pg. 23-24):

- Doctrine

- Ministry

- Church government/discipline

- Subscription

He apparently treated the third heading last in discussion, perhaps seeing #2 as naturally leading to #4. Or perhaps delaying the most contentious. Below are his complaints as he expressed them, following Barlow generally. Remember that his accuracy is solid in broad strokes but not always small details. He may be inaccurate in the order in which complaints were raised. Other accounts have a slightly different order. Links go to the appropriate page in Barlow unless otherwise indicated.

- That the Doctrine of the Church might be preserved in purity (Doctrine)

- The Articles of Religion need explained where obscure and enlarged where defective (Barlow 24-30; Usher 336; Usher 344)

- The catechism too brief (pg. 44)

- Reformation of the Sabbath Day desired (pg. 45)

- A new translation of the Bible desired (pg. 46-48; Usher 345)

- Unlawful and seditious books need banned (pg. 49; Usher 346)

- That good Pastors might be planted in all Churches (ministry, pg. 52-57; Usher 346)

- The ministry to be resident

- The ministry to be learned

- That the book of Common prayer might be fitted to more increase of piety (subscription) Their objections to subscription were as follows:

- Apocrypha (pg. 60-64; Usher 336; Usher 347)

- Incipits – (adding phrases like “Jesus said to the disciples” to introduce scripture readings in the liturgy – pg. 64)

- Interrogatories put to infants in baptism (pg. 64)

- The sign of the cross in baptism (raised by Knewstubs, pg. 67-76; Usher 349-50)

- The surplice (pg. 76-77; Usher 348)

- The word “worship” in the marriage vows (pg. 77)

- The ring in marriage (pg. 78)

- Churching of women (pg. 78)

- The Ex Officio Oath (Usher pg. 351)

- That Church government might be sincerely ministered (discipline)

Richard Bancroft, bishop of London, soon to become Archbishop of Canterbury, was one of two bishops representing conformity on day 2. He became the chief overseer of the KJB. Wikimedia Commons.

Rainolds was constantly interrupted by Bancroft, Bilson, and occasionally the king himself, who at one crucial point where Rainolds had the misfortune to mention “presbytery” took him to mean the Scottish presbytery that had caused such trouble in his homeland, which, “as well agreeth with a Monarchy, as God, and the Devil” (Barlow pg. 81). Jenny Wormald softens the king’s temper, remarking that “in the heat of debate, he was surely seeing not John Rainolds and his associates, moderate men all, but in response to Rainolds’ unlucky use of the word ‘presbytery’, seeing Andrew Melville and his extremist supporters.” Collinson suggests James may have been disingenuous. Whether Rainolds was referring to a Scottish presbytery or James actually thought as much didn’t matter: pretending that he was gave him the opportunity to assert the divine right of his monarchy. A long speech in a rebuking tone followed. “When I mean to live under a presbytery, I will go into Scotland again. But while I am in England, I will have Bishops,” James retorted (Usher pg. 351). At least twice James interjected the aphorism, “no Bishop, no king” (pg. 36, 84), warning that to threaten episcopacy was to threaten his monarchy.

Bancroft and Bilson made regular shows of conformity, bowing before the king or arguing for a “praying” against a “preaching” ministry. In these “fighting words” Lorie Anne Ferrell detects an attempt (pg. 142) to paint the Puritan spokesmen as aligned with treason. Bancroft muttered that these men the night before had “made a semblance” of joining the bishops and fighting for “nothing but unity” in the church yet now strike to “overthrow” it (Barlow pg. 26-27). Kneeling again, he begged his majesty to remember the canon that schismatics should not be heard against bishops. As Harley MS 828 puts it, Bancroft cast them into the extremist’s camp of Cartwright, adding with insult that, “they greatly abused his Majesty’s patience” by approaching him “in their Turkey gowns, more likely to conform themselves to Turks, than to the order of our Church.” The account claims unfoundedly that “Thomas Cartwright had taught them” this, “whose scholars they shewed themselves to be.”

Thomas Bilson, Bishop of Winchester, one of two bishops representing conformity on day 2, would later go on to serve as one of the final editors of the KJB, probably crafting the chapter summaries and possibly the dedication to King James. Wikimedia Commons.

We noted in our last post Carleton’s comment that the two companies differed in opinions as in fashions, one marching “in gowns and rochets and the other in cloaks and nightcaps.” This was the “vestments controversy” of the 1560’s re-enacted, the spicy insult of “turkey gowns” describing simple robes rather than priestly vestments, starkly out of place in the royal court. Rainolds defended them by claiming that in the universities they wore required gowns, “but abroad they might use such fashion of gown” as fit their calling. Bilson and Bancroft grumbled. “They should have worn priests gowns with tippets, and not these trunk gowns,” they retorted, adding that they might be legally punished for their offense. James lightheartedly admonished Bancroft, “My Lord, you are too hot in the beginning, and within a while after, now my Lord, you are more charitable” (Harley MS 828, in Usher Vol. II pg. 344). Of course, Barlow’s second Puritan account suggests that “the bishop of London behaved himself insolently” here (Barlow). “There was much stir about all the ceremonies and every point in it,” Dr. James Montague recorded. “They argued this point very long.”

An Example Discussion – The Apocrypha in Church and Bible

Each of the above points merits explanation, but this would take us afield of our purpose. Since we raised briefly in our treatment of the Millenary Petition the regular Puritan complaint that the Apocrypha was being printed in the Bible and read in the liturgy, we can examine some of the discussion on this point here as an example of how events can be pieced together from diverse accounts. Rainolds took occasion to “leap into” discussion of subscription (pg. 60). The Puritans would conform to a limited subscription, assenting to the 39 Articles and the Supremacy of James over the church, the first and third of Whitgift’s 1583 Articles (Bray 38). But the second article required affirming that the BCP contains “nothing in it contrary to the word of God” and that “he himself will use the form of the said book prescribed, in public prayer and administration of the sacraments, and none other.” This they could not do. Their first objection to subscription was “the books Apocryphal” which the BCP “enjoined to be read in the Church.” In them were “manifest errors, directly repugnant to the scriptures.”

Examples of Errors in the Apocrypha

Rainolds was ready with an example: Ecclesiasticus or Wisdom of Sirach 48:10, which he read as prophesying that Elias himself would come. Malachi 4:5 prophesied a coming of Elias that the NT saw as fulfilled in John the Baptist as forerunner of the Christ (Luke 1:17; Matt. 11:14). The text in Sirach implied that Christ and his coming did not fulfill prophecy. This then “implied a denial of the chief Article of our redemption.” It is strange that this is the example Rainolds chose, perhaps not so much that it was the one Barlow recorded. Rainolds had stronger examples to offer. In his special lectureship at Oxford beginning in 1585 he had delivered 250 lectures against the Catholic Bellarmine’s counting the Apocrypha as part of the canonical OT, Feingold explains, illustrating his arguments here. These were published posthumously in 1611. “After that many lectures,” Gordon Campbell quips, “any listener who was still awake would surely be convinced.”

Bancroft was not. He jumped up in rebuttal: such objection was nothing new, having been made for centuries by the Jewish apologists. These were books of antiquity, long in use by the Church. At this Thomas Bilson, bishop of Winchester, the other conformist representative, piled on. These books had been long accepted, as seen in the distinction allegedly from Jerome that these books weren’t part of the canon read to establish doctrine, but they were read [in the church] for instruction of manners, a distinction essential to reading of church councils (Barlow pg. 62).

James I, in 1604, wearing the famous “Mirror of Great Britain,” by artist John de Critz. Now at Montacute House. Wikimedia Commons.

James interrupted, concluding that he would “take an even order between both.” This was the typical Jacobean stance. He technically didn’t wish even all the canonical books read in the church, unless interpretation were given (which it usually wasn’t in the liturgy), nor any apocryphal book “wherein there was any error.” The distinction encouraged liturgical reading of the other Apocrypha, “which were clear, and correspondent to the Scriptures.” Of these James concluded, “he would have them read [in the liturgy of the church]” or else, James asked, “why were they printed [in the Bible]?” (pg. 62). He provided example of their profit in the church service by reading from the Book of Maccabees, which helps fill in the story of the persecution of the Jews, but isn’t sufficient to establish doctrines like sacrifice for the dead.

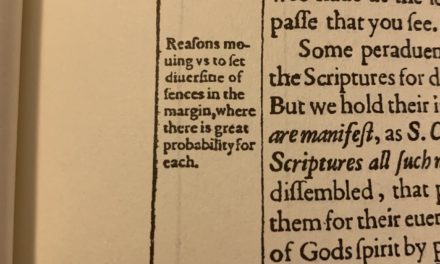

James Montague summarized: it was concluded that “nothing of the Apocrypha to be read that is in any part repugnant to the Scripture; but to be still read, yet as Apocrypha, and not as Scripture.” In the first of Usher’s anonymous accounts (CUL MS M.m.1.45) the summary is given, “For the Apocrypha, he [James] allowed and justified the use thereof” (Usher Vol. II pg. 336). Harley MS 828 gives a slightly different picture. “The King said he saw no reason but that they might be read [for instruction of manners] though not [for the edification of faith], as of ancient time hath been done in the Church.” When Rainolds alleged numerous errors “contrary to the Canonical Scriptures,” giving one or two examples, James “very learnedly argued,” and then conceded that “all such parts as had errors should be taken out, and others of them more sound read, which may best seem for explanation of the Scripture and instruction to good life.” Rainolds was charged to make a full list of these alleged errors. Perhaps 250 lectures should have produced one already.

Whitgift and Sparke

John Whitgift (c. 1530-1604), Archbishop of Canterbury. Oil on Canvas at Lambeth Palace. Artist unknown. Wikimedia Commons.

Rainolds was fortunate that Archbishop Whitgift was not in the Privy Chamber. Walter Travers recorded a conference in the 1580s between himself, Sparke, bishop Cooper, and Archbishop Whitgift, over Puritan complaints to the BCP, possibly caricaturing Whitgift (item 173 in Peel, modernized and lightly summarized below). When Whitgift asked for complaints, Sparke launched into prayer, only to be interrupted impatiently and ordered to spill it. (He squeezed in a short prayer anyway before he could be stopped.) The first complaint was about “the books appointed to be read in the Church for holy Scripture.” He divided “canonical and apocryphal.” The BCP problematically never scheduled readings from some parts of the OT, technically making it illegal to read them in Church. Adding fuel to fire, it regularly required readings from the Apocrypha, intimating that these had greater value than some of the OT.

Whitgift: “The books called Apocrypha are indeed parts of the Holy Scripture and of the Old Testament, they have been used to be read in the Church in ancient time, and they might and ought to be now read amongst us.”

Travers: Holy Scripture is a title reserved for the canon of the OT and NT, only applicable to books inspired by the Holy Spirit.

Whitgift: “The Apocrypha were likewise given by inspiration from God.”

Travers: Surely this could only be true in the general sense in which anyone saying “Christ is Lord” is inspired, not in the sense of producing a writing without error.

Whitgift: “You cannot show any error to be in the Apocrypha. They have bene held for Holy Scriptures by the ancient fathers, and so vouched and cited by them, as namely by Cyprian and by Augustine and divers other from the beginning of Christ’s Church, so always esteemed, and therefore read in the Church unto this day.”

Travers: Jerome distinguished between canonical and ecclesiastical books.

Whitgift, wearily: This “doubting of the Scriptures is a dangerous way for atheism to enter in by among us.”

Sparke Looks Back at Hampton Court

Now, debate continued in the Privy Chamber without Whitgift’s conservative voice. Sparke on this occasion was entirely silent. According to Anthony Wood in 1691, “he spoke not one word.” Whatever fire once burned in Sparke for the subject had since gone out. He was likely already a conformist, or on his way to it. In his 1607 recollection of Hampton Court he argues that he had always conformed (a document we look more closely at in a later post). He recounts the debate on this day in his preamble, referencing Barlow. “His Majesty’s order was, that none of the Apocrypha should be read at all, wherein there was any error. And therefore his highness willed Dr. Rainolds to note those chapters in the Apocrypha books, wherein such errors were, and to bring the note thereof to the Bishops.” He recounts Barlow suggesting that the preface to the second Book of Homilies (a major formulary of the Church of England, which the 39 Articles required assenting to and preaching annually) allows ministers to replace a prescribed OT reading with a NT one. It is doubtful such moderation truly came from Barlow. In any case, ingeniously, he suggests a compromise wherein a scheduled reading from the Apocrypha could be replaced by a NT reading at the minister’s discretion. He takes an entire chapter (chapter 10) to elaborate this compromise solution, arguing that conformity should thus be acceptable to the Puritans. It would never have worked. It required acknowledging the Apocrypha as part of the “Old Testament” which was precisely what the Puritans were unwilling to do. More important is his portrait of James and his view of the complaints, who “most wisely foreseeing” that even if concession was made to each,

it was likely enough that some things in the book, or within the compass of the urged subscription, would still seem unto some so harshly to remain set down, as that they would stick and stay thereat. His Highness most graciously signified unto us, that as it was our duty, so he wished every one of us, to construe and take everything in the best sense that we could, and not in the hardest and worst: for so only his intent and pleasure was, that they should be urged.

In the actual revised version of the BCP published later that year, only four minor changes to apocryphal readings were made (replaced Bel and the Dragon with Prov. 30, Aug. 26; Tobit 5,6 with Exodus 6, Joshua 20, 1 Oct.; Tobit 8 with Joshua 22, 2 Oct.) as detailed in the letter of James to Archbishop Whitgift on 09 Feb., 1604, (printed in Cardwell, pg. 221-22). Not the great victory for Rainolds that some have seen. As Ariel Hessayon points out, about 104 of 172 chapters of the Apocrypha continued to be read publicly in the liturgy of the church, compared with only 592 of 779 chapters of the canonical Old Testament.

Aftermath

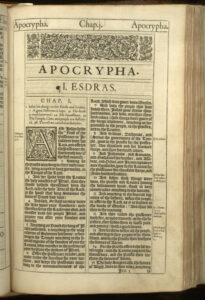

Start of the Apocrypha in the 1611 KJB. Absent is a dedicated title page. Typical running subject headings all say generally “Apocrypha” throughout each of the books. The title page of the KJB omits mention of Apocrypha, and the Table of Contents sandwiches them between canonical books without mention in the heading. Image credit Villanova University.

After James, Bancroft, and Bilson had all ganged up on Rainolds, James got out of his chair and retired briefly into his inner chamber, at which point heated discussion about the text in Ecclesiasticus continued among the lords (pg. 63). Such debates were perennial. Petitions like the Millenary Petition had expressed Puritan discontent with the role of the Apocrypha in the Church of England for some time. Scores of other examples could be listed. The 1611 KJB and its printing of the Apocrypha, we have before explained, comprise a sort of snapshot of this moment in history, when different forces were pulling in opposite directions. This moment is frozen for us in time in the KJB itself, which reaches neither the position of The Council of Trent and their Decrees on the Apocrypha nor the Confession of Faith of The Westminster Assembly. It rests instead somewhere ambiguously between these two bodies and their declarations, with a sort of “quasi-canonical” status that is complex, nuanced, and difficult to capture in simple terms.

The Day Ends

Craig explains the uniqueness of this day. It was “the only part of the conference which seems to have been anything like a disputation between two sides, since the puritans did not take part on Saturday and on Wednesday they were only to be called in to hear and accept what the King had concluded.” Indeed, he concludes, “with a different group of participants, and an opening speech by the King similar to that on Saturday, this session almost seems like a new conference” (Craig. pg. 265).

The day ended around 4:00 pm. “They had a cold pull of it and are utterly foiled,” Usher’s first anonymous account concludes, as the “triumph” they had long fought for. “Dr. Rainolds and his brethren are utterly condemned for silly men” (Usher Vol. II pg. 337). Oliver Ormerod, in his 1605 “The Picture of a Puritan” casts the Puritan spokesmen into the radical reformation borrowing language from the royal proclamation of 5 March 1604. As men “conformable to the state of the Church” gathered to hear “those which dissented,” the conference disappointed in its effects. James found the complaints “supported with so weak and slender proofs” that he and the Privy Council concluded that there was no reason why any changes at all should be made “in that which was most impugned, the Book of Common prayer” (BCP), nor in the doctrines, rites, or forms, of the church. James got out of his chair, and left for his inner chamber. As he did, he was heard muttering: “If this be all that they have to say, I shall make them conform themselves, or I will harry them out of the land, or else do worse.” Robert Cecil thanked God for giving them a king with such an “understanding heart.” Craig summarizes:

… the King conceded almost nothing of importance at the second session. The King and bishops had already dealt with the issue about ministry that Rainolds raised, as well as lay baptism and confirmation. The noxious ceremonies, on which their instructions had laid so much stress, remained, even though they had made the most moderate arguments against them. Aside from the plan for a new translation of the Bible the puritans won some additions to the catechism, an amendment of two sentences in the Sunday gospels, the removal of a few readings from the apocrypha, and the possibility that it might be considered whether a word, the wrong word at that, might be added to Article 16. It never was. The four were to come back on Wednesday and hear what the real conference had decided.

– Craig pg. 235-236

We come in our next post to the third and final day of the conference.

You wrote: “Walter Travers recorded a conference in the 1580s between himself, Sparke, bishop Cooper, and Archbishop Whitgift, over Puritan complaints to the BCP, possibly caricaturing Whitgift (item 173 in Peel, modernized and lightly summarized below).” I am assuming that this a reference to Albert Peel’s “The Seconde parte of a register : being a calendar of manuscripts under that title intended for publication by the Puritans about 1593, and now in Dr. Williams’s Library, London,” vol. 1, pp. 275-83 (1915).

I’m inclined to agree with your comment that Travers’ record may be caricaturing Whitgift (based on a perusal of Whitgift’s collected works), but I wonder whether you have any other reasons that support that conclusion.