[In our last few posts, we have examined the coming of King James I to the English throne, here, the text of the Millenary Petition made to him, here, and the impact which that Petition made, here. We now examine the structure of that Petition and probe into a few of its requests.]

Political maneuvers are an art form. Successfully making requests of a new monarch who had not yet made clear what direction his rule would take was an especially tedious form to master. One had to know what could be asked, and what could not; what was too much, and what too little. Further, one had to know how to go about structuring it all in a way that was palatable to a king whose greatest conviction was his own divine right. The golden rule of the art was, “Know thine own monarch.” The Millenary Petition presented to King James I in 1603 could be seen as an exercise in amateurs trying their hand at such an art.

The Tone Of The Petition

While the requests made in the Petition were moderate when compared with the more radical non-conformist agenda present in that age, it would be a mistake to judge them trivial. Buried within these terse, seemingly innocuous requests lay some of the very fault lines which, unresolved by the Hampton Court Conference in 1604, and worsened under the less skillful rule of James I’s son, would add fuel to the fire that ultimately splintered the nation into two decades of so-called Civil War(s). The petitioners were, as Collinson notes, “guarded in their requests,” but these requests were not unimportant to British unity, nor irrelevant to the history of the King James Bible. Space prevents examining each request, but some of the broader structure can be noted. George summarizes the content of the petition broadly, while McGrath explains at more length.

The Structure Of The Petition

The individual requests are sandwiched between introductory and concluding sections that make all the due posturing to the monarch, which assure the king repeatedly that they, “desire not a disorderly innovation,” and are neither, “factious men affecting a popular parity in the church,” nor, “schismatics aiming at the dissolution of the state ecclesiastical.” The requests then express complaint about “offenses,” all having to do with, “a common burden of human rites and ceremonies,” under four broad heads;

- In the church service

- Concerning church ministers

- For church living and maintenance

- For church discipline

Here, in this “centerpiece of Puritan agitation,” is a virtual laundry list of the religious tensions that separated the “spectrum of the discontented” that we have examined before from the established church prelacy. The Petition functions as a window into the past, through which the careful reader can glimpse the controversies within the church when James took the throne; indeed, it might tell us things about our own age if we listen closely enough. Gerald Bray helpfully enumerates the sections of these petitions into smaller units (read the full text of the Petition in our post here).

Some Example Requests

Start of the Millenary Petition in its first printing in 1603 in its refutation.

A few of the requests are worth looking at in more detail to give a representative sense of the whole.

That The Cross In Baptism May Be Taken Away

German Reformer Philipp Melanchthon administers the sacrament of Baptism to an infant. Attributed to Lucas Cranach the Younger.

Perhaps the most important of the requests relate to baptism (Bray’s 1.1-2). The Petition urged that, “the cross in baptism, interrogatories ministered to infants, confirmation, as superfluous, may be taken away: baptism not to be ministered by women, and so explained.” Baptism of a newborn infant had been an incredibly elaborate affair in the traditional church. In the early steps of English Reformation, much of that ritual had been pared down. The 1549 BCP still provided prescriptions for the form for infant baptism, with rituals for making the sign of the cross on the baby’s forehead, dipping him thrice or pouring water over him if weak, putting the white robe or chrisom on him, anointing him with oil, and blessing the baptismal water. In the 1559 BCP the various ceremonies at baptism had all but disappeared, with the lone exception of the sign of the cross.

Yet this single remaining ritual act became a symbol of much more. Puritans valued simplicity of service and despised what they regarded as empty ceremony, too reminiscent for them of a Catholic past. They were troubled by the practice of allowing it to be administered privately or by midwives, which, separated from the ministry of the word, would seem to grant it superstitious power. To retain even this simple symbol was to leave a signpost pointing to a prior age, and to suggest that the word was subordinate to liturgy.

These questions would be much debated at the Conference. The canons passed by Richard Bancroft after the Conference in 1604, with the authority of King James, declared that, “the Church of England hath retained still the sign,” and demanded that the sign, “may not be omitted,” (canon 30). The canon contained a lengthy and nuanced discussion of how the rite was to be interpreted, against the Puritan view.

Puritans typically refused to make the sign on the infant’s head. They generally used a simple basin or dish rather than the ornate baptismal font, and baptized wearing only a simple black gown instead of the more elaborate required surplice, which represented another of their complaints with the Elizabethan settlement.

That The Cap And Surplice Not Be Urged

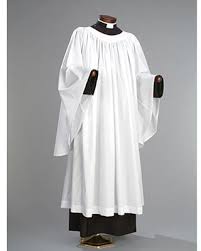

The surplice was a simple, white, typically sleeved, occasionally hooded, vestment that could be worn over a cassock (as here) or by itself for a more simple vesture.

The required use of the cap and surplice (Bray’s 1.3) by the clergy was a decades-old divide, part of the broader (and sometimes quite arcane) controversy over the use of vestments required of the clergy in the Elizabethan Settlement. The issue at hand wasn’t so much about clothing, as about what its continuing use by the clergy, and the monarchy’s claiming of the prerogative to regulate it, could be argued to represent. Clerical dress, MacCulloch explains, “might seem trivial until one realizes the symbolism involved: separate dress for the clergy…implied a continuing doctrine of a separately ordained priestly order within the reformed congregation of God’s people…”

James I of course was not completely unaware of the controversy surrounding these vestments, even if he claimed to be indifferent to it as a Scottish foreigner. At the Conference, after asking the plaintiffs what they thought of the cornered cap and, strangely, finding no resistance, William Barlow reported that he turned to the bishops and remarked, “you may now safely wear your caps, but I shall tell you, if you should walk in one street in Scotland, with such a cap on your head, if I were not with you, you should be stoned to death with your cap.”

He was (mostly) joking.

The famous 1527 portrait of Sir Thomas More by Hans Holbein the Younger shows a slightly earlier form of the square cap.

His famous Basilikon Doron, originally couched as a manual on kingship for his son, but repurposed and printed for the English with a new preface in 1603, became an instant bestseller to a people curious about this man who would likely become their king. He tried in his new preface to backtrack diplomatically and argue that his earlier attacking words about “Puritans” were actually aimed only at anabaptists. He was well aware, he claimed, that there were more moderate men (Puritans) who, “are persuaded that their bishops smell of papal supremacy; that the surplice, the cornered cap, and such like are the outward badges of popish errors.”

The final 1604 canons allowed that, “In the time of divine service and prayers in all cathedral and collegiate churches, where there is no communion, it shall be sufficient to wear surplices…” (canon 25). Canon 24 required, additionally, a cope when administering communion in a cathedral or collegiate church. They further required that, “Every minister saying the public prayers, or ministering the sacraments, or other rites of the church, shall wear a decent and comely surplice with sleeves, to be provided at the charge of the parish” (canon 58. cf. canon 17). “However,” Buchanan notes, “the issue in Elizabeth’s reign, and through until 1662, was not how to restrain Romanizers from wearing full eucharistic vestments, but how to get Puritans to wear even a surplice.”

Thomas Cranmer, with his square cap and beard (image has been touched up for clarity), in a portrait from Lambeth Palace. Artist unknown

The shape and form of the cap itself had evolved throughout the ages, and became a symbol of the present divide. Hargrave explains;

“For those of the church who approved of vestments, the square cap…became indicative of support for the mainstream Church of England and of obedience to episcopal and secular ordinance. For the Puritans the square cap was a dangerous symbol suggesting ongoing allegiance with the European Pope (in spite of the cap’s now explicitly English appearance), and one that denied ‘the priesthood of all believers’. Such an unbiblical adornment could not be justified. Polarized views of the square cap show that the square cap, whilst primarily remaining a piece of clerical attire, became a rallying point for sectarianism.

Puritan William Turner had even, according to legend, been so offended by the square cap that he had trained his dog to jump up and grab the objectionable hats off of the heads of those visiting clergy who had conformed.

One could say that he, at least, had a dog in the fight.

That The Canonical Scripture Only Be Read In The Church

The brief clause about the canonical Scriptures (Bray’s 1.13), requesting that the Apocrypha no longer be used in the liturgy, brings to the surface another tension in the Church of England in that age which is all too often forgotten; the status and right use of the Apocrypha in the church. Henry VIII repeatedly cited them as having biblical authority for example in The King’s Book, holding the near-universal view of that time. The Book Of Common Prayer of Cranmer contained numerous readings and lessons from the Apocrypha, just as it did the OT and NT. The two official books of Homilies, which ministers were required to publicly read or preach in their churches throughout the year, repeatedly cited apocryphal texts authoritatively, alongside OT and NT texts.

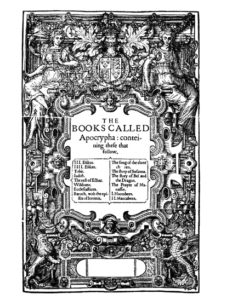

Title page of the Apocrypha in the 1602 Bishops Bible which the KJB revised.

The Articles of Religion (first 42, then 38, then 39) which shaped official church doctrine could be seen as somewhat ambiguous about the issue. On the one hand they upheld the Homilies, declaring in Article XXXV that these homilies, “contain a godly and wholesome doctrine,” and that, “therefore we judge them to be read in churches by the ministers diligently and distinctly, that they many be understanded of the people.” This then vindicated the authoritative use of the Apocrypha in the Homilies. Further, the Elizabethan injunctions of 1559 required the Homilies to be preached quarterly.

Still interwoven then into the weekly worship of the church in all of its basic “formularies” was respect for these books as the word of God.

Yet, on the other hand, Article VI, in the form modified by Archbishop Matthew Parker in 1563, made a firm declaration concerning the Apocrypha against the declaration of the Council of Trent (1545).

Trent, during its fourth session, had entered into some two months of nuanced discussion on the so-called “wide canon” on Feb. 12, 1545. O’Malley explains that Augustin Bonuccio eventually won consent to the plan to affirm the earlier Council of Florence, but, importantly, not to take a stand on the disputed question of the authority of the Apocrypha that had historically divided such great fathers of the church as Jerome and Augustine. In one of the most surprising moves of the Council, the decree itself ended up merely reacting against emerging Protestant views. He points out that the, “absolutely crucial qualification of the decree may have been clear to the prelates at the council, but the text they produced gave no hint of it.” He goes on to sympathetically argue that the Council was misunderstood at this point, but even he must admit that, “In this case at least, the council itself must be held responsible for the misunderstanding.” Bishop Westcott later complained bitterly about how uninformed the Council’s decision was, and how little right they had to make, “this fateful decree,” so out of line with historic Christian consensus.

The modified Article VI then reacted against this over-reaction from Trent, re-asserting Jerome’s position that the apocryphal books were helpful for life and manners, but not authoritative for establishing doctrine;

And the other books as Hierome [Jerome] saith, the Church doth read for example of life and instruction of manners, but yet doth it not apply them to establish any doctrine.

Yet none of the earlier strands exalting the Apocrypha and its use were removed. Further complicating the issue is the foundation on which the authority of the canon was to be recognized. In distinction to the common Protestant theological grounding in the internal witness of the Spirit, Article VI grounded its authority of the canon rather on its reception in the church, asserting dubiously (most would say, flat out unhistorically) of the authority of the sixty-six-book-canon that there, “was never any doubt in the church.”

Thus, within the formularies of the Church of England were both vestigial attitudes still pointing in an old direction, and fresh attitudes pointing in newer ones; an ambiguity that provided grounding for later Anglo-Catholics to assert that Article VI had no authority, and to conclude that the “true” Anglican position was identical to the Tridentine. They surely pressed the ambiguities too far.

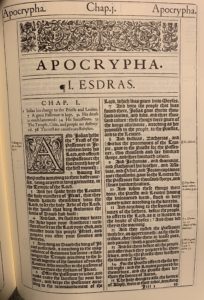

Start of the Apocrypha in the 1611 KJB. Notably absent is a dedicated title page. Also notable is that the typical running subject headings all simply say “Apocrypha” throughout each of the books.

The status of the books in official church doctrine was in the process of moving further away from the Council of Trent’s declaration that they are fully authoritative, on a trajectory towards the later declaration of the Confession of Faith of the Westminster Assembly, in 1647. This confession finally revived the voice of the old Puritan impulse in a statement that the books, “not being of divine inspiration, are no part of the Canon of the Scripture; and therefore are of no authority in the Church of God, nor to be any otherwise approved, or made use of, than other human writings.” Yet official Church of England doctrine never arrived at the point of view of this esteemed later confession. The members of the Assembly, when they insisted that the apocryphal books are, “not to be recommended as anything but ancient human writings,” Van Dixhoorn notes bluntly (pg. 11), were directly, “contradicting the teaching of the Church of England.”

We might note, indeed, an opposite trajectory in James himself, who was, it could be argued, evolving in his own views. At roughly the time of the creation of the KJB, he was moving from the broadly “Scottish” position of sharp denunciation of the Apocrypha which he expressed in some earlier statements (such as those in his Basilkion Doron), to a more “English” position of higher, though nuanced, reverence for them which would characterize his English reign (such as those in his literary war with Bellarmine as the KJB was being worked on, where he asserted agreement with the position of Rufinus).

The 1611 KJB and its printing of the Apocrypha, it turns out, comprise a sort of snapshot of that precise moment in history, when different forces were pulling in opposite directions; a moment frozen for us in time in the KJB itself, which reaches neither The Council of Trent nor The Westminster Confession of Faith, but rests, somewhere, ambiguously, between these two bodies and their declarations. The Apocrypha retains its ecclesiastical usage, and its use for life and manners; it is a regular part of preaching, study, and even memorization, but has no authority to establish doctrine. It is printed as part of the Bible, but is not seen as part of the inspired canon. It is suspended somewhere between Trent and Westminster, both of which it judges to be extremes that alter the historic Christian position, holding a kind of quasi-canonical status. There it must remain frozen, in a very English manner. This despite the fact that the KJB has long since been most commonly printed without these books (which can best be purchased separately in a CUP printing, or within the excellent NCPB KJB edited by David Norton), a complex story which Hill recounts. There is much more of this story that needs to be told, but it is a tale for a later time.

A Concluding Prelude To The Conception Of The King James Bible

We can see then, in examining just three of the requests of the Millenary Petition, that even the most overlooked clauses of this obscure document can disguise to a modern reader the sharp tensions that existed in the Church of England just before the Hampton Court Conference. Some of these tensions would quite literally shape the production of the King James Bible, and indeed, the entire direction of the Church of England moving forward. But they are as yet in our history only requests to a coming monarch. In terms of the King James Bible and its history, the Petition is most important as a prelude to the Conference. To see what discussion it generated, and what impact the final decisions had on the King James Bible itself, we must visit the Conference itself, one of the most famous in the Church of England’s history, and look over the shoulders of the prelates and Puritans there, when the King James Bible was itself conceived

To that Conference we will turn in our next few posts.

Comments