Our last two posts (here and here) traced activities of the first two days of the Hampton Court conference. This post overviews the final day and reflects on the conference as a whole.

Hampton Court Day Three – Wednesday, 18 January 1604

The final day happened in two parts. The first session was most important, treating and deciding issues not yet settled. The second session essentially publicized these decisions. The Puritan spokesmen were present only at the second.

Session One

John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, from a 1602 painting at Lambeth Palace. Wikimedia Commons.

The first session lasted some two hours. The king conferred with the bishops, deans, some of the doctors and knights of the arches, and some lawyers. Archbishop John Whitgift reported on the issues the bishops had been commissioned to resolve (the three the king himself had raised on Saturday, as well as Rainold’s new point about incipets). The king further raised the issues of the rubric in private baptism, the high commission, and the ex officio oath. Bancroft reiterated Whitgift’s 1583 Articles (Bray #38), to which ministers must conform. James approved of requiring subscription.

As the issues were reviewed, James referred them to special sub-committees. Toby Matthew noted that James listed some initial names “whom he thought fittest to be employed” for these committees (pg. 165). Robert Cecil was charged with keeping the official list of decisions and committees. One copy, titled “A Memorial of some principal matters, to be considered of by the Lords of the Privy Council…” is contained in British Library Manuscript Cotton Cleopatra F II, folio 120r-v. It may be viewed in the British Library Digital viewer here. It summarizes ecclesiastical decisions and lists chosen commissioners.

Notable for this blog is the decision “that care be taken that one uniform translation of the Bible be printed and read in the church. And that without any notes” (orthography modernized). At this stage, just as James proposed, the Privy Council was involved and planned to oversee the production of the KJB. This vision would not be carried through. We look at other copies of these recorded decisions in a later post analyzing the sources recording the decision to produce a new translation.

Record of decision to print a new Bible, British Library Cotton MS Cleopatra F II, folio 120r. Click thumbnail to enter British Library Digital viewer.

Session Two

At the second session, the Puritans were called in: not for their input, but to be given orders about what had been decided without it. Toby Matthew recorded that they were required “to receive such order and direction as [James] should be pleased to give” (pg. 164). He “presently signified, what was done, and caused the alterations, or explications before named, to be read unto them” (Barlow pg. 99).

The issue of the marriage vow in the BCP, “with my body, I thee worship,” reappeared. Rainolds objected on day two to this wording, a long-standing Puritan complaint. Only God should be worshiped; current wording idolized wives. James mocked his singleness, quipping that “many a man speaks of Robin Hood who never shot a bow; if you had a good wife yourself, you would think all the honor and worship you could do to her would be well bestowed.” Now it was suggested that the vow be changed to “worship and honor” to soften its sense, a change never made. James now saw “that the exceptions against the communion book were matters of weakness” (Barlow pg. 100).

James VI and I, in 1604, wearing the famous “Mirror of Great Britain,” by artist John de Critz. Wikimedia Commons.

Laurence Chadderton begged temporary exception in Lancashire to the requirement of clergy wearing the surplice (see some of the context behind this in our posts here and here). Bancroft protested: if letters of exception were granted Chadderton they would “fly over all England” (Barlow pg. 103). Everyone would ask the same. As if on cue, Knewstubs went down on his knee to ask exemption for Suffolk. James agreed with Bancroft: no exceptions.

According to Barlow, the Puritans “all gave their unanimous assent, taking exception against nothing that was said or done, but promised to perform all duty to the Bishops, as their Reverend fathers” (Barlow pg. 101). Bancroft dropped to his knees again in dramatic fashion proclaiming that “his heart melted within him…with joy” (Barlow pg. 96) at the king’s wisdom. Barlow concludes with a fawning picture of James and exaggerated Puritan acquiescence:

Finally, they jointly promised to be quiet and obedient, now they knew it to be the King’s mind to have it so. His Majesty’s gracious conclusion was so piercing…that it fetched tears from some on both sides. My Lord of London [Bancroft] ended all, in the name of the whole company, with a thanksgiving unto God for his Majesty…[who] departed into the inner Chamber, all the Lord’s presently went to the Council Chamber, to appoint Commissioners, for the several matters before referred (Barlow pg. 99-100).

Not all saw things tied with Barlow’s neat bow. Arnold Hunt’s analysis of Chadderton’s annotated copy of Barlow’s Sum and Substance reveals that Chadderton initially agreed that their duty was “to hear and obey his majesty’s pleasure.” Something about it rubbed him wrong. He crossed out “and obey” (pg. 219 here).

The Third Day Evaluated

All the accounts agree that the third day, “saw the most important issues decided by the King with the advice of his bishops and of his Privy Council, and without any reference to the petitions or the petitioners, except to ask them to promise to accept the conclusions reached without their aid.” (Craig pg. 240). At no point did “equal representatives” of two “sides” meet to debate their differences. The bishops were treated as the legitimate ecclesiastical authorities, advising the king, while the Puritan spokesmen were only allowed to present a dissenting case, itself judged by the king and bishops together. “At no point did representatives for two sides meet in the kind of formal conference that the puritans seem to have wanted, and which Henry Jacob was still calling for two years after Hampton Court” (Craig pg. 240).

The Anti-Puritanism of James and Bancroft

James was clear on how he treated the Puritans. Writing after the second day to Lord Henry Howard, member of his Privy Council, he recounted:

MS. BL. Cotton Vespasian F III Fol. 76r at the British Library – James VI and I To Lord Henry Howard, Jan. 16-18, 1604. Click thumbnail image to enter British Library viewer.

We have kept such a revel with the puritans here these two days as was never heard the like, where I have peppered them as soundly as ye have done the papists there….They fled me so from argument to argument, without ever answering me directly [as is their custom] as I was forced at last to say unto them that if any of them had been in a college disputing with their scholars, if any of their disciples had answered them in that sort, they would have fetched him up in place of a reply, & so should the rod have plyed upon the poor boys buttocks. I have such a book of theirs as may well convert infidels, but it shall never convert me except by turning me more earnestly against them (fol. 76r here, transcribed and lightly modernized; c.f. Akrigg, letter #101).

These words are considered by Curtis to be “in word and tone…filled with hyperbole” (Curtis pg. 12). He thought James friendlier to Puritanism than this. Yet stronger distemper appears in letters to Whitgift, his council, and Robert Cecil (Akrigg #98, #102, #118) and in a series of royal proclamations (Larkin/Hughes #35, #30, #41). James excoriated Scottish presbyterianism as “Puritanism” in Basilikon Doron (written for his son Henry) in “sharp and bitter words.” The manuscript, written in his own hand in 1598 in Middle Scotts, kept at the British Library, may be viewed here. He admonished Henry to “take heed” to “such puritans” who were “very pests in the Kirk [church] and common-wealth of Scotland; whom by long experience I have found no deserts can abolish, oaths nor promises bind, breathing nothing but sedition & calumnies, aspiring without measure, railing without reason, and making their own imaginations without any warrant of the word the square of their conscience” (modernized from f. 12r-v here).

Basilikon Doron (The Royal Gift), from British Library Royal MS 18 B XV folio 12v. Click thumbnail image to enter British Library digital viewer.

A revised edition appeared in English in 1603, part of aspirations to the English throne, becoming a bestseller among a nation curious about the king. James backpedaled, claiming his earlier angry words about Puritanism narrowly described an anabaptist sect, “the Family of Love” (see Sommerville pg. 5-7 here), rather than the English movement. Fear of problems English Puritanism might cause his accession birthed the disingenuous claim. James concluded the fear unwarranted after the conference. His son Charles I later found Puritanism a stronger force than either ever anticipated.

James put a fine point on it in a speech to parliament on 19 March 1604. He found on his accesion three groups “lurking within the bowels” of England: 1) conformist protestantism, which he professed, and which was “by the law maintained”; 2) Roman Catholicism, “another sort of Religion”; and, 3) Puritanism, “a private sect”:

The first is the true Religion, which by me is professed, and by the Law is established. The second is the falsely called Catholics, but truly, Papists. The third, which I call a sect rather then Religion, is the Puritans and Novelists, who do not so far differ from us in points of Religion as in their confused form of Policy and Parity, being ever discontented with the present government, and impatient to suffer any superiority, which maketh their sect unable to be suffered in any well-governed Commonwealth. But as for my course toward them, I remit it to my Proclamations made upon that Subject.

(Lightly anglicized and modernized from Sommerville, pg. 138; for the proclamations referred to see Larkin/Hughes #35, #30, #41.)

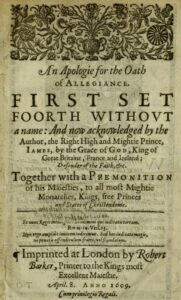

English Puritanism’s identification with Scottish presbyterianism earned international audience in 1609 when James attached a massive Premonition to the European rulers to a copy of his Apology for the Oath, which he now owned authorship of, during the long controversy with Cardinal Bellarmine. (James Montague claimed in 1616 that Lancelot Andrewes wrote the Apology, based on notes from James, pg. 35 in the 1616 Works). James defended his words in Basilikon Doron, spoken “ten times more bitterly of them nor of the Papists; having in my second edition thereof affixed a long Apologetic Preface, only in odium Puritanorumi” (pg. 44-47 here). Alan Cromartie rightly concludes that “the evidence suggests that James was in practice more hostile to puritan dissent than even the most authoritarian bishops” (pg. 62).

Bancroft’s disapproval, known from Anti-Puritan writings and actions before the conference (see Collinson here) reappear in the canons drafted in its wake. Convocation passed these in 1604, turning conference decisions into law. They demanded sharp conformity to the new edition of the BCP, its government, and liturgy, remaining in force until 1969 (Bray #8).

Interpreting the Conference – Embittered Battle or Round Table?

Ken Fincham remarks of the conference that “the event and its wider outcomes continue to be debated by modern historians.” Classic treatments (Cardwell, Strype, Gardiner, Usher, etc.) remain helpful. The claims of Mark Curtis (and advances in historical methodology) sparked modern reassessments from diverse angles. Some major ones include:

- Mark Curtis, influentially and mistakenly reviving a Puritan-friendly picture in 1961,

- S.B. Babbage in a half-hearted appraisal of Bancroft’s Anti-Puritanism in 1962,

- B.W. Quintrell, pressing the vexing question of deprivations after Hampton Court in 1980,

- Frederick Shriver, rightly correcting Curtis, in 1982,

- Peter Lake in his moderation of Puritanism in 1982,

- Collinson, responsively reassessing the treatment in his thesis, in 1983,

- Ken Fincham, from the perspective of diocesan response in 1985,

- Fincham and Lake together, in broader assessment of royal ecclesiastical policy, in 1985,

- Nicholas Tyake, refocusing English dispute on Arminianism, in 1987 (pg. 9ff. here),

- Peter White, with tenuous and almost opposite conclusions, in 1992 (pg. 140-152),

- Arnold Hunt, examining Chadderton’s annotations to Barlow, in 1998 (pg. 207-228 here),

- W.B. Patterson, reimagining James as global peacemaker, in 1997 (pg. 31-74 here),

- Lorie Anne Ferrell through the lens of polemical rhetoric here in 1998,

- Robert Oliver in a paper briefly overviewing the conference in 2004,

- Diana Newton, reevaluating James’ initial English reign based on her Phd work, in 2005,

- Alan Cromartie, painting an essentially Laudian James, in 2006,

- Colin Buchanan, in a helpful edition of the main documents, with analysis, in 2009,

- A. Kenneth Curtis, in a chapter celebrating the KJB’s quatercentenary, in 2009,

- Bernard Bourdin, analyzing the Oath of Allegiance controversy, (pg. 96 ff), in 2010,

- Bracy Hill, analyzing 18th century historiography of Hampton Court and the KJB in 2011,

- Collinson a final time, in a reassessment of Bancroft and Anti-Puritanism, in 2011,

- Ferrell again, splitting private and liturgical Bible reading, in 2015 (pg. 261-271 here).

- Joshua Rodda, along the way in focused reassessment of scholarly disputation, in 2016,

- John Morgan, through the lens of Henry Jacob’s “reason-of-state” language, in 2017,

- Ken Fincham again, for the official ODNB entry on the conference, in 2018,

- John Morgan again, seeing Jacobean policy as an act of fervent anti-popularity, in 2018.

This is to say nothing of the spate of books on the KJB (e.g., Norton, McGrath, Nicolson, Opfell); English Bible history (Daniell, etc.); biographies of James (Stewart, Croft, Wormald, Willson, Lee, etc.); or British histories, which all typically treat the conference. Craig’s PhD work from 2007 remains the most thorough analysis to date and should have completely settled long-standing debates. Instead it has been completely ignored, save a small journal article summarizing a single chapter. Cromartie employed similar methodology on a smaller scale, and his thesis is immensely strengthened by the work of Craig. No one has cared to notice.

The widely influential thesis of Mark Curtis that the reactions of the Puritans to the conference were “on the whole favorable,” that the conference was only looked upon as a “failure” because in its “aftermath” the state didn’t make good, and that “the worsening of factional struggles within the church” resulted not from any disparate treatment of the Puritans at the conference but from a later negligence to carry out Hampton Court’s decisions, need to be finally laid to rest in their grave. Whatever Hampton Court was, it was not an even hearing of two sides, nor any fair battle between them. In his magisterial thesis on Puritanism in 1957, popularized in 1967, Patrick Collinson wisely urged avoiding such romanticizing. Puritan and conformist voices existed on a spectrum without a unified voice. Further,

Such decisions as were made at Hampton Court were more indicative of a round-table conference than of the disputations which changed the faith of other parts of Europe in the years of the Reformation. Some of the matters on which the king agreed to act were not at all controversial in their nature…Others were, in effect, neutralized by royal orders made at or after the conference, notably the authorization of a new English Bible (pg. 459 here).

While the “two-party description of Hampton Court” finds precedent in contemporary accounts (Craig pg. 256), close examination renders it wrongheaded. Even if “the conception of the conference began as a meeting of two sides presided over by the King, it became a brief meeting of one side with a King who was supported by the other side” (Craig pg. 268-269). If James intended to be an impartial moderator, “he did not confine himself to that role very long” (Craig pg. 268). Craig’s thesis strengthens and lightly modifies Collinson’s conclusion that the conference “did the puritan cause positive harm.” It was now crystal clear “that James was as hostile to the very principles of dissent and nonconformity as ever Elizabeth had been” (Collinson, pg. 461).

Debate remains about who chose the Puritan spokesmen and how well they represented Puritan interests (see Morgan here, analyzing the complaints of Henry Jacob). Yet the evidence sweeps away any doubt that the Puritans were snubbed. This was “the king’s own conference” as Craig termed it in the title of his dissertation. It was a “round-table” not in that all parties had equal audience with the king, but in that James was fully in charge and invited members to the table to play roles he dictated. The presence and arguments of the four Puritan spokesman, far from driving the conference as usually thought, made virtually no difference to its decisions in the end. Dissenting clergy weren’t included in any major decisions or even discussions. James “allowed four ministers, who were probably not chosen by the larger body of puritans, to present their case at one session of the conference, but all in all, if the meeting with the four ministers had not taken place, the outcome of the conference at Hampton Court would not have been much different” (Craig pg. 271).

The Request for a New Translation

This brings us to the point at which we can finally look more closely at the request by Rainolds for a new translation with a full historical context for understanding it. Information from the diverse accounts which Craig highlighted has often been ignored in treatments of Hampton Court focusing on the KJB which rely narrowly on Barlow’s account, perhaps with brief notes from one or another additional accounts. An imperfect image of the request for a new translation has resulted. What motivated this request? Was it planned ahead of time or was it a spur of the moment decision? What was Reynolds really seeking? Was the request sincere? Why did James to agree to it? These questions and more we take up in our next post, as we compare all the extant accounts of this motion for a new translation and propose a fresh interpretation of the request.

Comments