King James Bible History

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut condimentum scelerisque dapibus. Proin eget diam euismod.

Hampton Court – Attendees

The Hampton Court conference in 1604 not only set the direction for the Church of England’s future, it also was the context in which the King James Bible was first conceived. At least, the mature form of it that later came to fruition. In our last post on the conference, we examined the palace itself and the dates on which the conference was held. To fully grasp the import of the conference and its impact on the King James Bible, we must also say what we can about those who attended. Many men would work on the KJB, and we will specifically note which of those men were present at this moment in its prehistory. Yet this requires first saying something briefly about the contemporary sources that are extant.

The Sources – Faithful Accounts?

The two major sources for the Hampton Court conference, sometimes at odds, are, first, the semi-official account which William Barlow was asked to write up, a participant in the conference, and later head of the Second Westminster Company of Translators for the KJB. In his, “The Sum And Substance Of The Conference…” he takes a decidedly more positive view of the bishops, and presents the king as supportive of episcopacy and dismissive of the Puritans. Second is an anonymous account printed in Usher (sometimes called the “Harliean Account”), which presents a more positive account of the Puritans, presents James as largely supportive of them, and takes a quite dim view of the bishops. There are also more than a dozen additional contemporary accounts that contribute to our picture of the conference. Because such data will likely interest only the super-nerds, we have placed it all in a separate post here which most readers can safely ignore. For reasons detailed in that post on sources, and contrary to Nicolson, Curtis, and some others, we take Barlow as a largely faithful account that has been vindicated, and follow his narrative in this and the next few posts, supplementing it where needed with the other sources.

Known Hampton Court Conference Attendees

Ken Fincham suggests some forty-two individuals who might have been at the conference. But he names only eleven accounts he is working with. William Craig, working with sixteen accounts (plus a number of what he calls “post-conference documents) names in his dissertation some sixty-six men that might have been present at the conference. Sometimes it is hard to speak with certainty. For example, King James had nearly doubled the size of Elizabeth’s privy council to twenty-four men. Seventeen of these could conceivably have been present, while thirteen most likely were. Yet only ten of these men are directly mentioned in an extant source. Thus we can only firmly say that ten of them attended. Using such a tight criterion to determine attendees, we can note the following chart of those who we know attended some part of the conference. The Puritan spokesmen are highlighted, while the name of anyone who went on to work on the KJB is underlined.

Chart of the known attendees of the Hampton Court conference. Puritan Speakers are highlighted. KJB creators are underlined.

KJB Creators Present At The Conference

-

- King James I

- Bishop of London Richard Bancroft, (later Archbishop of Canterbury)

- Bishop of Winchester Thomas Bilson

- Dean of Winchester George Abbot (later Archbishop of Canterbury)

- Dean of Westminster Lancelot Andrewes

- Dean of Chester William Barlow

- Dean of Worcester Richard Edes

- Dean of St. Paul’s John Overall

- Dean of Christ Church Thomas Ravis

- Dean of Windsor Giles Tomson

- Laurence Chaderton

- Dr. John Rainolds

Major Players

Some major characters are worth noting in more detail. John Whitgift was the archbishop of Canterbury at the time, the highest ecclesiastical office in England apart from the King himself. He played a major role in some important parts of the conference. But as we will see when we walk through the events of the conference, during the second day, when the KJB was proposed, he sent two representatives in his place. He choose instead to meet with the other bishops in order to comply with the king’s orders to settle certain issues among themselves. First was Richard Bancroft, who we will discuss below, and second was bishop of Winchester Thomas Bilson. He would later work as one of the final editors of the King James Bible, probably crafting the para-textual material.

The four Puritan spokesmen, John Rainolds, Laurance Chaderton, John Knewstubs, and Thomas Sparke, spoke for the group which was the precipitating cause of the conference. Rainolds and Chaderton both went on to work as translators in two of the Hebrew Companies of translators (Chadderton at Cambridge on I Chronicles-Song of Songs and Rainolds at Oxford on the Prophets).

Delegates?

How do we rightly think of these men? They are often refereed to as the Puritan “delegates” or “representatives,” but this can in fact be a bit misleading. As this conference was taking place, somewhere not far away, some thirty of the less moderate Puritans were meeting at the same time, who had not been invited to the conference. In one of his earliest treatments of the conference, the veteran historian of Puritanism, Patrick Collinson, explained, “Not a hundred miles from the Privy Chamber at Hampton Court, ‘at the conference but not in place’, there was a gathering of some thirty ministers representing eleven counties and four towns.” (pg. 37-38). These men included Author Hildersham, who, as we have seen, likely drafted the Millenary Petition, Thomas Wilcox, Stephen Egerton, and Henry Jacobs.

They were the ones pressing upon the king for change. They had drawn up a list of instructions for the spokesmen at Hampton Court to follow. Yet, as Collinson concludes, “This robust statement was not adequately expressed, or represented, by the four spokesmen who appeared for the Puritans” at the conference. These men had not even been allowed to decide who would be at the conference to give voice to their concerns. The king and bishops it seems rather most likely made this choice, quite intentionally picking some of the most moderate voices. These “hotter” Puritans (especially Henry Jacobs) later complained that they had not been represented accurately at the conference. As Jacobs put it, “Most of the persons, appointed to speak for the Ministers, were not of their choosing, nor nomination, nor of their judgment in the matters then and now in question, but of a clean contrary.” Yet this was no mistake or oversight; it was likely by design. The four men who voiced Puritan concerns at the conference are thus better thought of as “spokesmen” than as representatives or delegates.

In any case, the two men who really shone at the conference, especially on the second day most relevant to the KJB, were John Rainolds, the leading Puritan spokesman, and Richard Bancroft, the ultimate Anti-Puritan.

John Rainolds

John Rainolds (1549-1607) seems to have been sent to Oxford at the age of eight (though probably he was sent back home shortly). He returned as a student in 1562, first at Merton College, then at Corpus Christi College. He came to Oxford as a Catholic, like his father and much of his family. But over the course of several years, he gradually converted to Protestantism, becoming in the late 60’s a Puritan in every sense of the word, though a moderate one. This was a status held with enough conviction that he was entrusted with tutoring young Richard Hooker, who would go on to become perhaps the most influential theologian of the Church of England. He graduated MA in 1572 and was elected Greek reader at Corpus. His lectures were immensely popular, but he resigned the position in order to devote more time to the study of theology.

He slowly emerged as the face of the Puritan moment at Oxford, getting caught up in a number of controversies along the way. He agitated Queen Elizabeth I on a few occasions, who saw him as a bit too extreme. He labored to refute both the Catholic Bellarmine, arguing against accepting the Apocrypha as Scripture, and the eccentric controversialist Hugh Broughton, with his precise and detailed chronological reading of Scripture. The latter fight followed him for nearly a decade.

In 1598 he was installed as Dean, and then as president, of Corpus Christi, a post he held until his death, greatly increasing the future of Corpus. By the time of the Hampton Court conference, he had become one of the most widely respected Puritan leaders in England. It was only natural then that he would become a kind of informal spokesman for the Puritan cause at the conference. As Mordechai Feingold notes, “Rainolds’s name appeared on every list of puritan candidates that had been circulated the previous summer and autumn. When the historic occasion arrived, it was he who led the puritan delegation.” Feingold goes on to explain that Rainolds, in the midst of controversy after the conference, proceeded,

in what he clearly regarded as the most important project of his career—and the only tangible result of the Hampton Court conference—the new translation of the Bible. The task was divided among six groups, and Rainolds was part of the one charged with translating both major and minor prophets. Although officially headed by John Harding, the regius professor of Hebrew, the group met at Rainolds’s lodgings at Corpus three times a week, a practice that continued even during the last weeks of the president’s life.

Joseph Hall spoke of the towering genius of Rainolds shortly after his death, saying, “He alone was a well furnished library, full of all faculties, full of all studies, of all learning; the memory, the reading of that man, were near to a miracle.”

Richard Bancroft

Richard Bancroft came to Cambridge as a slightly older man than was common in that day, but graduated BA in 1567, and proceeded MA from Jesus College in 1572. Known for his reputation in boxing, wrestling, and other competitive sports, he developed a firm no-nonsense tone that seemed to cross over into his academic work. He was soon ordained priest in the diocese of Ely at the age of thirty. He was admitted DTh at Cambridge in April 1585. He curried royal favor, becoming treasurer of St. Paul’s Cathedral by royal prerogative in 1586, and becoming a canon of Westminster in 1587.

A Famous Sermon

He increasingly became known as the major spokesman for conformity. He waged a battle throughout his career against Catholics on the one hand, and Puritans on the other. In his famous St. Paul’s Cross sermon in 1589, which drew battle lines talked about for decades, he controversially argued against the Puritans that episcopacy (church structure built on bishops, who rule in an administrative capacity over multiple churches and over other lower ministry positions, grouped together into dioceses, under the king as true head of the church) was not only a biblically acceptable model, it had in fact continued since apostolic times with apostolic authority as the only approved model. In that sermon he reacted sharply against the charges of the anonymous Martin Marprelate;

Bishops have had this authority, which Martin condemeth, ever since the evangelist S. Mark’s time. Besides, in the most flourishing time of the church, that ever happened since the apostles’s days, either in respect of learning, or of zeal, Martin and all his companions opinion hath heerin been condemned for an heresy. Lastly, there is no man living, as I suppose, able to show, where there was any church planted ever since the apostle’s times, but there the Bishops had authority over the rest of the ministry.”

[Spelling/punctuation updated slightly in all citations of Bancroft.]

By a striking association, he connected the Puritans with both modern schismatics and ancient heretics, condemning them all alike as those who, “by schism and heresy divided themselves from the church of God, and rent in sunder by their factions the peace thereof.”

Beyond just Martin, Cranfield explains, “Bancroft’s homily had another intended target: those who exalted the word of God to the point that it became the sole authority that, by preaching and prophesyings, threatened the balance within a church that set greater store by the use of sacraments” (pg. 4). These he denounced as false prophets. While some reformers were proposing the principle of Sola Scriptura, arguing that every man – even those not ordained and trained in the church – had a right to read the Scriptures for himself, Bancroft denounced them as missing the Augustinian principle that, “faithful ignorance is better than rash knowledge.” Indeed, “It falleth not within the compass of every man’s understanding to determine and judge in matters of religion…but of those who are well experienced and exercised in them.” As Cranfield insightfully recognizes, Erasmus and Tyndale had hoped the ploughboy in the field would each have the Scriptures to read for themselves. But for Bancroft, such democratized readers would only become, in his words, “the prattling old woman, the doting old man, the brabling sophister.” They think they are understanding Scripture by reading it, but since they do so without the aid of the ordained bishop, they actually, “tear it in pieces, and take upon them to teach it before they have learned it.” He had little interest in such ploughboys reading Scripture for themselves.

A Legacy Of Anti-Puritanism

Bancroft’s ministry was largely marked by the campaign against Puritanism and a related defense of episcopacy. In 1597 Bancroft assumed the role of the Bishop of London, increasing his reach. While he maintained some personal friendships with several of the more moderate Puritans, he was, as Collinson terms it, “the arch Anti-Puritan.”

Nowhere does this become more clear than in his actions and comments at the Hampton Court Conference. He immediately opposed the suggestion for a new translation, and yet, as we will see, was soon placed by the king as head over the entire project of creating it. Alister McGrath suggests that part of the reason for this reversal must have been because he saw the importance of protecting the interests of the Church of England from both Catholics and Puritans. His position of oversight would further allow him the right of limiting the translators in their freedom.

Bancroft had realized that it was better to create a new official translation that he could influence than to have to contend with the authorization of the Geneva Bible. It was decidedly the lesser of two evils. He was in a position to exercise considerable influence over the new Bible, by laying down rules of translation that would ensure that it would be sympathetic to the position and sensitivities of the established Church of England. And finally, he would be in a position to review the final text of the translation, in case it needed any judicious changes before publication.

A final reason that was “significant to his thinking” likely further motivated this reversal. That is, his own career ambitions. As McGrath goes on to explain;

To support the new translation would be to win the royal favor. Whitgift, the ailing archbishop of Canterbury died in February shortly after the conclusion of the Hampton Court Conference. His successor would be appointed from among the present bench of bishops. Bancroft was the front runner for preferment. Yet promotion lay in the king’s gift, precisely because of the royal supremacy that Bancroft so persuasively espoused. From February onward, Bancroft knew that he had no option if he wanted to secure the see of Canterbury. He would have to make sure the king’s new translation project went ahead smoothly—whatever his personal views on the matter.

Bancroft was politically on the rise, with his eye sharply upon the Archbishop’s chair, a role which he likely assumed unofficially behind the scenes even before Whitgift passed. If his plan was to use the new translation to please the king in order to firmly secure his coveted see, it worked. He was formally confirmed as Archbishop of Canterbury on 10 December 1604. He was then able to more thoroughly, “reconstruct the English Church,” from a place of power, in the phrase that shaped Usher’s classic title.

King James VI And I

King James I himself, was, of course, the most important attendee of the conference. He had appointed himself moderator, everything that happened was ultimately centered around him, and all final decisions were his. It was, as Craig terms it in the title of his dissertation, “The King’s Own Conference.” James was in control, in every way someone could be. Fincham explains that, “All in all, this was a singularly unusual conference, dominated by the king who acted, at different times, as prosecutor, witness, judge, and jury, and used the discussions to demonstrate his theological learning and caustic wit” (pg. 3-4).

James I, in 1604, wearing the famous “Mirror of Great Britain,” by artist John de Critz. Now at Montacute House.

We have examined already some of the details of the life of James and his rise to the English throne. It suffices here to note that while the circumstance that he came from presbyterian Scotland likely gave the Puritans some hope that they would find favor in his eyes, his actual history fighting the presbyterians in his first kingdom made virtually the exact opposite the case, at least at first. He was as committed to episcopacy as anyone else in the English Church, because of how it bolstered his own ideas of the Divine Right of kings. He was thus less interested in moving the Church in a Puritan direction than he was in dealing with what he saw as a pesky problem that needed a preemptive strike to bring a peaceful resolution. While he would come later to have a more balanced perspective on Puritans and at least some of their demands, they had the misfortune of appearing at the conference, in his eyes at least, to be yet another manifestation of the obstacles to his power raised by presbyterians in Scotland like Andrew Melville. As Jenny Wormald explained (pg. 37), the conference “was held too early in the reign” to produce the positive results the Puritan spokesmen wanted.

James was challenging hardline Elizabethan attitudes too soon for success; and he had not yet fully realized how different from his Scottish presbyterians were the English puritans he met at Hampton Court. Hence his furious and famous outburst, ‘no bishop, no king’; in the heat of debate, he was surely seeing not John Rainolds and his associates, moderate men all, but in response to Rainolds’s unlucky use of the word ‘presbytery’, seeing Andrew Melville and his extremist supporters. Hence his lack of opposition to Bancroft’s extensive deprivations of puritan clerics in 1605–6; deprivation was a weapon he had used in Scotland himself. Nevertheless, Hampton Court was a landmark of importance, in the longer if not the immediate term.

The presence of these three men – James, Rainolds, and Bancroft – at the Hampton Court conference would end up profoundly shaping the final product. The KJB ended up being caught in the middle of an ecclesiastical tug-of-war. Rainolds and the Puritans he spoke for pulled the translation in one direction, representing Puritan interests, while Bancroft, with much more power, pulled it in another, directly opposing those interests and supporting episcopacy. James controlled it all, ensuring that Bancroft had final decisions. It would end up being Bancroft’s Bible, far more than it would Rainolds’s. And that, as we will see, made all the difference in the end.

The Events Of The Conference

But what actually happened at the Conference? What was on the agenda, and whose agenda was it? How did the suggestion of a new translation come about? What did it mean? What was decided? What happened in the “aftermath” of the conference, to use one author’s phrase? And more importantly, how did all of this lead to the creation of the King James Bible?

To these questions we will turn in our next few posts.

Posts On The Hampton Court Conference

Hampton Court – Avenue And Dates

The Hampton Court conference in 1604 was described by Frederick Shriver as, “one of the most significant events in the political and religious history of England.” It set the course for the future of the Church of England and determined the role that the Puritans would – or rather, wouldn’t – play in the official Church. Some have perceived the seeds of the English Civil War (now more commonly called “the wars of the three kingdoms”) being planted at this conference. Indeed, given the colonization of the New World by the Puritans as they increasingly found less room for them in the English church, one could even say that this conference shaped the future of religion and politics in North America. In terms of both religion and politics, it is thus an event of historical importance worth exploring.

We have traced already the discontent with the elizabethan settlement that found new life breathed into it at the coming of King James VI of Scotland to the English throne. Some were content with the way religion had settled under Elizabeth. Others, primarily the Puritans, were convinced that the English church, which retained so much ceremony from the traditional church, was, “but halfway reformed.” They were deeply troubled and discontented with this state of affairs. We have looked in depth at the Millenary Petition, which was the prime expression of such discontent, and at some of the specific requests which it made of the new king. The king eventually arranged the Hampton Court conference to deal with the issues these Puritans kept raising and complaining about. Or, more accurately, to deal with the pesky Puritans who were always raising them.

Our primary interest is, of course, more narrowly on the history of the King James Bible itself. Yet it was at this conference that the King James Bible was first conceived, and because the politics of the conference heavily shaped the end product, the conference is worth looking at in some detail in its own right. In this post we will trace broadly the avenue where the conference took place, and the dates on which it took place – the when and where, so to speak. In the next post we will examine the roster of attendees, then look more closely at the events of the conference before finally zooming in on the request for a new translation which ultimately resulted in the creation of the KJB.

The Avenue – Hampton Court Palace

Hampton Court palace itself is an architectural and historical wonder. A full documentary on the palace can be watched in the window above, or a briefer one here. It was built by Cardinal Wolsey in the early 16th century, and, upon his fall from grace, became the palace of King Henry VIII. Henry made numerous expansions of the already extravagant structure, including adding the Bayne tower which extended the lavish state apartments that Wolsey had created. The Anne Boleyn Gateway and the famous Astronomical Clock remain impressive sights for tourists even today.

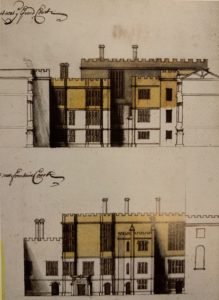

A rare detailed view of the rooms the conference was held in, from East and West sides, prior to the 1732 reconstruction, attributed to Thomas Fort (Souden/Worsley, pg. 113).

The clock, a technological marvel of its age, tells the time, the phases of the moon, the signs of the zodiac, the movement of the sun (plotting the earth as the center of the universe around which it revolves of course) and even the time of high tide at London Bridge. Those attending the conference would have looked out the windows, across Fountain Court, now called Clock Court, and seen this prominent clock telling the time. They would also have seen the marvelous marble fountain in the center of the court which Elizabeth had built just a few decades before, which no longer exists today.

By the time James took the English throne, there were three basic functional zones through which a visitor would pass to approach the king’s presence, each getting progressively closer to the king, and each protected by guards who were instructed to only let someone through if they were approved and met the requisite dress/title requirements to “level up.” The three zones, according to Thurley (pg. 104-105), were;

- The Outer Rooms

- Great Hall

- Watching Chamber

- Chamber of Estate

- Presence Chamber

- The Privy Lodgings

- King’s Dining Chamber

- King’s Privy Chamber

- King’s Bed Chamber

- King’s Study

- Bath

- The Secret Places

Visitors would come from the Great Hall into the Watching Chamber hoping to get a glimpse of the king if he came through. Moving beyond that point access became more restricted. Most of the conference took place in the king’s Presence Chamber and Privy Chamber, with some small parts taking place in a private withdrawing chamber.

The Great Hall (through the doors to the right) leads into the Watching Chamber (photographer’s position). From the Watching Chamber, through the small doors pictured on the left, approved visitors entered the king’s Presence Chamber. Photo Credit – Tudor Travel Guide

Gustavus Paine noted in his classic account of the KJB Translators that, because of reconstruction, “no one can now see the spot where Rainolds stood when he proposed the translation.” And indeed, various parts of the palace have undergone massive reconstruction during the last half millennium. Unfortunately, the state apartments became so broken down and dilapidated by the early eighteenth century that the whole section was significantly rebuilt by William Kent in 1732 under King George II. That section, where the Hampton Court conference took place, would have been roughly around what is now Cumberland Suite, part of which is occupied by an art gallery today, on the second of three stories (the first story in British counting). Some of this section is no longer open to the public, though some adventurous sorts have somehow made it in anyway, and went on to write about it at the Tudor Travel Guide, where a reader can also see some modern day images of the court from that section.

However, we know far more of the history of the architecture now than Paine did in his day. Based on historical accounts of the construction, and vestigial remains of the old structure, historians have reconstructed what that section of the palace looked like at the time. A basic floor plan of the second floor, with a cutout of the rooms where the conference took place highlighted, can be seen below. A Google Maps satellite image of the palace as it stands today can be seen here, while a modern photo of the entrance to the king’s Presence Chamber can be seen above. As we will see in later posts, the shape of the architecture itself and the successive access it provided to the king created a setting to make the Puritans feel even less welcome than they already did, and foreshadowed in some ways the conclusions of the conference.

The second floor of Hampton Court palace under King James I, with the rooms concerning the conference highlighted in a cutout, based on a reconstructed sketch by Daphne Ford, in Thurley, pg. 78.

The Dates – Changed And Hectic

The conference was originally scheduled for 1 November 1603 at Whitehall, but the plague had hit London, eventually killing almost a quarter of the capital’s population, which meant a delay and a change of venue. On 24 October, James issued a proclamation postponing till January and moving to Hampton Court. Even the title of this proclamation, Concerning Such As Seditiously Seek Reformation In Church Matters, bluntly revealed his attitude towards the Puritans. Curtis examines that proclamation, and the changes made between an early draft form of it and its final published form, here.

The move to Hampton Court created a bustle of activity and celebration. Three companies of players were there for the Christmas celebrations and more, including William Shakespeare, who was resident playwright and part owner of the King’s Men. Several of his plays were performed at the court in the Great Hall; A Midsummer Night’s Dream for sure, probably also Twelfth Night, Troilus And Cressida, Henry IV, Parts I and II, Henry V, and Hamlet.

Masques were popular as well. Queen Anne even performed the part of Pallas in Samuel Daniel’s Masque, The Vision Of The Twelve Goddesses, on 8 January 1604, with twelve of her ladies in waiting.

It seems that the conference was first rescheduled for Thursday, 12 January 1604. But given that it was a hectic time of attending to visiting dignitaries, at the last minute the plans were changed again and it was rescheduled to start Saturday, 14 January. While rumors of the latest change spread as late as the night of the 11th, the bishops apparently were not sure how true they were, and so they showed up on the morning of the 12th ready to start the conference as originally planned. This resulted in what we could call an unplanned “pre-conference” meeting between just the king and bishops that Thursday. Then followed, on three non-consecutive days (Saturday, Monday, and Wednesday), the three days of the conference proper.

In fact, because some who write on the conference today don’t always canvass the whole range of sources (more on those sources in our coming posts), confusion about the dating still exists, made worse by the common confusions about the old and new style dating, and when to begin the new year. For example, Thurly, pg. 108, mistakenly dates this first “pre-conference” to 10 January, while Gerald Bray (pg. 820 fn. 1) following only the account of Patrick Galloway (who includes the pre-conference meeting and thus dates the conference 12-18) states mistakenly that the three days of the conference were the 12th, 16th, and 18th. In reality, the dates as they ended up working out were as follows;

-

- Tuesday, 1 November, 1603 – Originally scheduled first day (cancelled)

- Thursday, 12 January, 1604 – Pre-conference meeting (unscheduled) between bishops and king

- Saturday, 14 January, 1604 – First day of the conference

- Monday, 16 January, 1604 – Second day of the conference

- Wednesday, 18 January, 1604 – Third (final) day of the conference, in two parts

But Who Was There?

We have examined the avenue and dates on which the conference took place. But to fully understand the events of the conference and its significance we must also understand who was present for it. To this roster of attendees our next post will turn.

Posts On The Hampton Court Conference

The Structure And Requests Of The Millenary Petition

[In our last few posts, we have examined the coming of King James I to the English throne, here, the text of the Millenary Petition made to him, here, and the impact which that Petition made, here. We now examine the structure of that Petition and probe into a few of its requests.]

Political maneuvers are an art form. Successfully making requests of a new monarch who had not yet made clear what direction his rule would take was an especially tedious form to master. One had to know what could be asked, and what could not; what was too much, and what too little. Further, one had to know how to go about structuring it all in a way that was palatable to a king whose greatest conviction was his own divine right. The golden rule of the art was, “Know thine own monarch.” The Millenary Petition presented to King James I in 1603 could be seen as an exercise in amateurs trying their hand at such an art.

The Tone Of The Petition

While the requests made in the Petition were moderate when compared with the more radical non-conformist agenda present in that age, it would be a mistake to judge them trivial. Buried within these terse, seemingly innocuous requests lay some of the very fault lines which, unresolved by the Hampton Court Conference in 1604, and worsened under the less skillful rule of James I’s son, would add fuel to the fire that ultimately splintered the nation into two decades of so-called Civil War(s). The petitioners were, as Collinson notes, “guarded in their requests,” but these requests were not unimportant to British unity, nor irrelevant to the history of the King James Bible. Space prevents examining each request, but some of the broader structure can be noted. George summarizes the content of the petition broadly, while McGrath explains at more length.

The Structure Of The Petition

The individual requests are sandwiched between introductory and concluding sections that make all the due posturing to the monarch, which assure the king repeatedly that they, “desire not a disorderly innovation,” and are neither, “factious men affecting a popular parity in the church,” nor, “schismatics aiming at the dissolution of the state ecclesiastical.” The requests then express complaint about “offenses,” all having to do with, “a common burden of human rites and ceremonies,” under four broad heads;

- In the church service

- Concerning church ministers

- For church living and maintenance

- For church discipline

Here, in this “centerpiece of Puritan agitation,” is a virtual laundry list of the religious tensions that separated the “spectrum of the discontented” that we have examined before from the established church prelacy. The Petition functions as a window into the past, through which the careful reader can glimpse the controversies within the church when James took the throne; indeed, it might tell us things about our own age if we listen closely enough. Gerald Bray helpfully enumerates the sections of these petitions into smaller units (read the full text of the Petition in our post here).

Some Example Requests

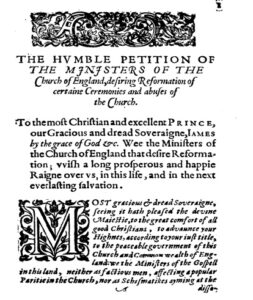

Start of the Millenary Petition in its first printing in 1603 in its refutation.

A few of the requests are worth looking at in more detail to give a representative sense of the whole.

That The Cross In Baptism May Be Taken Away

German Reformer Philipp Melanchthon administers the sacrament of Baptism to an infant. Attributed to Lucas Cranach the Younger.

Perhaps the most important of the requests relate to baptism (Bray’s 1.1-2). The Petition urged that, “the cross in baptism, interrogatories ministered to infants, confirmation, as superfluous, may be taken away: baptism not to be ministered by women, and so explained.” Baptism of a newborn infant had been an incredibly elaborate affair in the traditional church. In the early steps of English Reformation, much of that ritual had been pared down. The 1549 BCP still provided prescriptions for the form for infant baptism, with rituals for making the sign of the cross on the baby’s forehead, dipping him thrice or pouring water over him if weak, putting the white robe or chrisom on him, anointing him with oil, and blessing the baptismal water. In the 1559 BCP the various ceremonies at baptism had all but disappeared, with the lone exception of the sign of the cross.

Yet this single remaining ritual act became a symbol of much more. Puritans valued simplicity of service and despised what they regarded as empty ceremony, too reminiscent for them of a Catholic past. They were troubled by the practice of allowing it to be administered privately or by midwives, which, separated from the ministry of the word, would seem to grant it superstitious power. To retain even this simple symbol was to leave a signpost pointing to a prior age, and to suggest that the word was subordinate to liturgy.

These questions would be much debated at the Conference. The canons passed by Richard Bancroft after the Conference in 1604, with the authority of King James, declared that, “the Church of England hath retained still the sign,” and demanded that the sign, “may not be omitted,” (canon 30). The canon contained a lengthy and nuanced discussion of how the rite was to be interpreted, against the Puritan view.

Puritans typically refused to make the sign on the infant’s head. They generally used a simple basin or dish rather than the ornate baptismal font, and baptized wearing only a simple black gown instead of the more elaborate required surplice, which represented another of their complaints with the Elizabethan settlement.

That The Cap And Surplice Not Be Urged

The surplice was a simple, white, typically sleeved, occasionally hooded, vestment that could be worn over a cassock (as here) or by itself for a more simple vesture.

The required use of the cap and surplice (Bray’s 1.3) by the clergy was a decades-old divide, part of the broader (and sometimes quite arcane) controversy over the use of vestments required of the clergy in the Elizabethan Settlement. The issue at hand wasn’t so much about clothing, as about what its continuing use by the clergy, and the monarchy’s claiming of the prerogative to regulate it, could be argued to represent. Clerical dress, MacCulloch explains, “might seem trivial until one realizes the symbolism involved: separate dress for the clergy…implied a continuing doctrine of a separately ordained priestly order within the reformed congregation of God’s people…”

James I of course was not completely unaware of the controversy surrounding these vestments, even if he claimed to be indifferent to it as a Scottish foreigner. At the Conference, after asking the plaintiffs what they thought of the cornered cap and, strangely, finding no resistance, William Barlow reported that he turned to the bishops and remarked, “you may now safely wear your caps, but I shall tell you, if you should walk in one street in Scotland, with such a cap on your head, if I were not with you, you should be stoned to death with your cap.”

He was (mostly) joking.

The famous 1527 portrait of Sir Thomas More by Hans Holbein the Younger shows a slightly earlier form of the square cap.

His famous Basilikon Doron, originally couched as a manual on kingship for his son, but repurposed and printed for the English with a new preface in 1603, became an instant bestseller to a people curious about this man who would likely become their king. He tried in his new preface to backtrack diplomatically and argue that his earlier attacking words about “Puritans” were actually aimed only at anabaptists. He was well aware, he claimed, that there were more moderate men (Puritans) who, “are persuaded that their bishops smell of papal supremacy; that the surplice, the cornered cap, and such like are the outward badges of popish errors.”

The final 1604 canons allowed that, “In the time of divine service and prayers in all cathedral and collegiate churches, where there is no communion, it shall be sufficient to wear surplices…” (canon 25). Canon 24 required, additionally, a cope when administering communion in a cathedral or collegiate church. They further required that, “Every minister saying the public prayers, or ministering the sacraments, or other rites of the church, shall wear a decent and comely surplice with sleeves, to be provided at the charge of the parish” (canon 58. cf. canon 17). “However,” Buchanan notes, “the issue in Elizabeth’s reign, and through until 1662, was not how to restrain Romanizers from wearing full eucharistic vestments, but how to get Puritans to wear even a surplice.”

Thomas Cranmer, with his square cap and beard (image has been touched up for clarity), in a portrait from Lambeth Palace. Artist unknown

The shape and form of the cap itself had evolved throughout the ages, and became a symbol of the present divide. Hargrave explains;

“For those of the church who approved of vestments, the square cap…became indicative of support for the mainstream Church of England and of obedience to episcopal and secular ordinance. For the Puritans the square cap was a dangerous symbol suggesting ongoing allegiance with the European Pope (in spite of the cap’s now explicitly English appearance), and one that denied ‘the priesthood of all believers’. Such an unbiblical adornment could not be justified. Polarized views of the square cap show that the square cap, whilst primarily remaining a piece of clerical attire, became a rallying point for sectarianism.

Puritan William Turner had even, according to legend, been so offended by the square cap that he had trained his dog to jump up and grab the objectionable hats off of the heads of those visiting clergy who had conformed.

One could say that he, at least, had a dog in the fight.

That The Canonical Scripture Only Be Read In The Church

The brief clause about the canonical Scriptures (Bray’s 1.13), requesting that the Apocrypha no longer be used in the liturgy, brings to the surface another tension in the Church of England in that age which is all too often forgotten; the status and right use of the Apocrypha in the church. Henry VIII repeatedly cited them as having biblical authority for example in The King’s Book, holding the near-universal view of that time. The Book Of Common Prayer of Cranmer contained numerous readings and lessons from the Apocrypha, just as it did the OT and NT. The two official books of Homilies, which ministers were required to publicly read or preach in their churches throughout the year, repeatedly cited apocryphal texts authoritatively, alongside OT and NT texts.

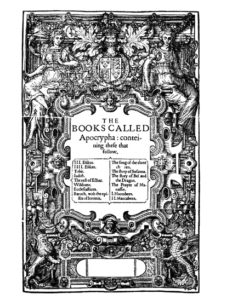

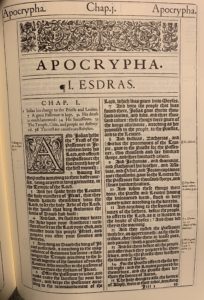

Title page of the Apocrypha in the 1602 Bishops Bible which the KJB revised.

The Articles of Religion (first 42, then 38, then 39) which shaped official church doctrine could be seen as somewhat ambiguous about the issue. On the one hand they upheld the Homilies, declaring in Article XXXV that these homilies, “contain a godly and wholesome doctrine,” and that, “therefore we judge them to be read in churches by the ministers diligently and distinctly, that they many be understanded of the people.” This then vindicated the authoritative use of the Apocrypha in the Homilies. Further, the Elizabethan injunctions of 1559 required the Homilies to be preached quarterly.

Still interwoven then into the weekly worship of the church in all of its basic “formularies” was respect for these books as the word of God.

Yet, on the other hand, Article VI, in the form modified by Archbishop Matthew Parker in 1563, made a firm declaration concerning the Apocrypha against the declaration of the Council of Trent (1545).

Trent, during its fourth session, had entered into some two months of nuanced discussion on the so-called “wide canon” on Feb. 12, 1545. O’Malley explains that Augustin Bonuccio eventually won consent to the plan to affirm the earlier Council of Florence, but, importantly, not to take a stand on the disputed question of the authority of the Apocrypha that had historically divided such great fathers of the church as Jerome and Augustine. In one of the most surprising moves of the Council, the decree itself ended up merely reacting against emerging Protestant views. He points out that the, “absolutely crucial qualification of the decree may have been clear to the prelates at the council, but the text they produced gave no hint of it.” He goes on to sympathetically argue that the Council was misunderstood at this point, but even he must admit that, “In this case at least, the council itself must be held responsible for the misunderstanding.” Bishop Westcott later complained bitterly about how uninformed the Council’s decision was, and how little right they had to make, “this fateful decree,” so out of line with historic Christian consensus.

The modified Article VI then reacted against this over-reaction from Trent, re-asserting Jerome’s position that the apocryphal books were helpful for life and manners, but not authoritative for establishing doctrine;

And the other books as Hierome [Jerome] saith, the Church doth read for example of life and instruction of manners, but yet doth it not apply them to establish any doctrine.

Yet none of the earlier strands exalting the Apocrypha and its use were removed. Further complicating the issue is the foundation on which the authority of the canon was to be recognized. In distinction to the common Protestant theological grounding in the internal witness of the Spirit, Article VI grounded its authority of the canon rather on its reception in the church, asserting dubiously (most would say, flat out unhistorically) of the authority of the sixty-six-book-canon that there, “was never any doubt in the church.”

Thus, within the formularies of the Church of England were both vestigial attitudes still pointing in an old direction, and fresh attitudes pointing in newer ones; an ambiguity that provided grounding for later Anglo-Catholics to assert that Article VI had no authority, and to conclude that the “true” Anglican position was identical to the Tridentine. They surely pressed the ambiguities too far.

Start of the Apocrypha in the 1611 KJB. Notably absent is a dedicated title page. Also notable is that the typical running subject headings all simply say “Apocrypha” throughout each of the books.

The status of the books in official church doctrine was in the process of moving further away from the Council of Trent’s declaration that they are fully authoritative, on a trajectory towards the later declaration of the Confession of Faith of the Westminster Assembly, in 1647. This confession finally revived the voice of the old Puritan impulse in a statement that the books, “not being of divine inspiration, are no part of the Canon of the Scripture; and therefore are of no authority in the Church of God, nor to be any otherwise approved, or made use of, than other human writings.” Yet official Church of England doctrine never arrived at the point of view of this esteemed later confession. The members of the Assembly, when they insisted that the apocryphal books are, “not to be recommended as anything but ancient human writings,” Van Dixhoorn notes bluntly (pg. 11), were directly, “contradicting the teaching of the Church of England.”

We might note, indeed, an opposite trajectory in James himself, who was, it could be argued, evolving in his own views. At roughly the time of the creation of the KJB, he was moving from the broadly “Scottish” position of sharp denunciation of the Apocrypha which he expressed in some earlier statements (such as those in his Basilkion Doron), to a more “English” position of higher, though nuanced, reverence for them which would characterize his English reign (such as those in his literary war with Bellarmine as the KJB was being worked on, where he asserted agreement with the position of Rufinus).

The 1611 KJB and its printing of the Apocrypha, it turns out, comprise a sort of snapshot of that precise moment in history, when different forces were pulling in opposite directions; a moment frozen for us in time in the KJB itself, which reaches neither The Council of Trent nor The Westminster Confession of Faith, but rests, somewhere, ambiguously, between these two bodies and their declarations. The Apocrypha retains its ecclesiastical usage, and its use for life and manners; it is a regular part of preaching, study, and even memorization, but has no authority to establish doctrine. It is printed as part of the Bible, but is not seen as part of the inspired canon. It is suspended somewhere between Trent and Westminster, both of which it judges to be extremes that alter the historic Christian position, holding a kind of quasi-canonical status. There it must remain frozen, in a very English manner. This despite the fact that the KJB has long since been most commonly printed without these books (which can best be purchased separately in a CUP printing, or within the excellent NCPB KJB edited by David Norton), a complex story which Hill recounts. There is much more of this story that needs to be told, but it is a tale for a later time.

A Concluding Prelude To The Conception Of The King James Bible

We can see then, in examining just three of the requests of the Millenary Petition, that even the most overlooked clauses of this obscure document can disguise to a modern reader the sharp tensions that existed in the Church of England just before the Hampton Court Conference. Some of these tensions would quite literally shape the production of the King James Bible, and indeed, the entire direction of the Church of England moving forward. But they are as yet in our history only requests to a coming monarch. In terms of the King James Bible and its history, the Petition is most important as a prelude to the Conference. To see what discussion it generated, and what impact the final decisions had on the King James Bible itself, we must visit the Conference itself, one of the most famous in the Church of England’s history, and look over the shoulders of the prelates and Puritans there, when the King James Bible was itself conceived

To that Conference we will turn in our next few posts.

Posts On The Millenary Petition

The Creation And Impact Of The Millenary Petition

[In our last two posts, we examined the religious and political climate at the time of the coming of King James I to the English throne (here), and presented the full text of the Millenary Petition (here). In this post we will zoom in on the creation of the Petition and ask what impact it had.]

Discontent is a universal human experience throughout time. How it comes to expression has a more complex history. The digital world in which we live has made “complaint” a fairly common and astoundingly easy task. Amazon reviews can be penned in seconds from a smart phone (they even send a link directly soliciting your opinion). All manner of social networking apps allow you to rate people, places, and services, with whatever rank of “stars” you wish, with comments included. That’s to say nothing of now almost antiquated methods of complaint, like writing an actual email to a support address, or, if anyone remembers how, penning an actual snail-mail letter. (I’ve read that it involved some kind of barbaric murder of trees, then stuffing their dead carcasses with lead, which were then used to bruise and leave marks on other parts of their dead family members’ mutilated carcasses. Somewhere there was some savage-like licking with the tongue involved.) Of course, all such methods are only effective if someone is willing to listen, and the methods quite frustrate themselves and their users when the one being complained to simply turns a deaf ear.

The Creation Of The Millenary Petition

In reality, new technology has only facilitated formal complaint; it did not invent it. Forums in which to express discontent existed in late Elizabethan England as well. We are not so different from them as we might like to suppose. As we have explained, there was a wide spectrum of discontent hiding under the surface of the Church when James VI rode south to accede to the English throne; some of it far more weighty than what you wrote in your last Amazon review.

The so-called Millenary Petition, technically titled, The Humble Petition Of Ministers Of The Church Of England, Desiring Reformation Of Certain Ceremonies And Abuses Of The Church, was one of about a half dozen petitions reportedly made to James while he was on his way to London from Edinburgh for his coronation between 4 April and 7 May 1603. It was most likely devised and drafted by Author Hildersham, probably under the influence of Stephen Egerton, a kind of “party leader” of the moderate non-conformists at the time (Fuller connected both names to it, though he also confusedly thought it was finished after the Hampton Court Conference rather than before it). Hildersham may even have been among those who presented the Petition to the king, though the circumstances of the presentation are shrouded in uncertainty.

But what was the result of their Petition?

The Impact Of The Millenary Petition – New Proposals

Most writers have taken it as common knowledge that the Petition (which, contrary to its own claims and its later ill-adopted nickname, was not signed by anything like 1,000 ministers) was the cause of the calling of the Hampton Court Conference in 1604 at which the King James Bible was ultimately conceived.

Connections Commonly Stated

Derek Wilson in his popular history is one of a dozen modern examples stating the common view that, “they asked the king to summon a conference at which all the abuses in the religious life of the nation could be discussed,” and even claiming an emotive impact of the Petition on the king;

The king welcomed the Millenary Petition. He was flattered to be invited to sort out the religious differences within his new kingdom. He would, he decided, begin his reign with a gracious irenical initiative to bring peace and unity to his subjects. He pondered the petition during his leisurely southward progress during the summer and it was while he was staying with the earl of Pembroke in his Wiltshire home, Wilton House, on 29–30 August 1603 that he gave orders for a meeting [the Hampton Court Conference], “for the hearing, and for the determining, things pretended to be amiss in the church”.

– Wilson, Derek. The People’s Bible. Lion Hudson. Kindle Edition.

Connections Challenged

Yet William Craig has recently argued (in a lecture here and a more academic article here), quite the contrary. He suggests that James actually called the Conference of his own accord, that is was not a response to the Millenary Petition, and that it was not so much an attempt to hear Puritan complaints as it was an attempt to ensure that Puritans would stay under his thumb.

It is all very well to say that “It is well known” that “the Hampton Court conference resulted from King James’s favorable response” to the Millenary Petition’s request for a conference, but if this knowledge has no contemporary evidence to support it, then historians must read the evidence again…. Although we cannot know it beyond doubt, it seems likely that the conference was the king’s own idea.

– William Craig, Hampton Court Again, pg. 48.

He raises a number of factors to support his claims. Some of the most important can be highlighted here (citing from his journal article). First, the king already had a well-established track record in Scotland of calling such conferences when he saw issues that needed handling with a royal touch. This was his regular M.O., and he needed no outside impetus to prompt such an action. Indeed, he called three of them in 1604 alone.

Second, the language of the Petition that has been cited as requesting the Conference (“…if it shall please your Highness further to hear us, or more at large by writing to be informed, or by conference among the learned to be resolved…”) is exceptionally vague. “Conference” is only one of three different proposals, and in any case, “In the early seventeenth century, ‘conference’ could mean anything from a simple conversation to a formal meeting between representatives of the two Houses of Parliament” (pg. 55).

Third, the surviving invitation of participants to the Conference makes no mention of being a response to any Petition. It seems to assert rather that the Conference was at the king’s own wish. “It does not refer to the Millenary Petition, but says that the king wished ‘to confer and advise with some of the bishops and others of the clergy of this realm, of some matters of importance concerning ecclesiastical causes'” (pg. 63).

Fourth, and perhaps more important, as Craig demonstrates, no contemporary accounts link the Petition and the Conference, a connection only made by later historians. No mention is made of the Petition in the official archives, nor even in contemporary histories as related to the Conference. No mention is made of it in the official account of the accession, despite its narrating some five petitions made during the journey of James to London. In fact, even in later accounts, the given date and location of the presentation of the Petition is amazingly inconsistent and unsettled; not what one would expect from a Petition so impactful as to have moved to the king to call a major royal Conference to resolve it.

Fifth, the Conference itself doesn’t appear at all by its format to have been intended as a means to hear Puritan complaints. Almost twenty some odd “avant-grade conformists” (to use another historian’s term) were present while only four Puritan delegates were present, and these four were only allowed at one day of the Conference, the king hearing from the bishops and making decisions entirely without them the rest of the Conference. As has been noted before, “The conference…made it perfectly clear that James was on the side of the Establishment and expected all others to conform, crying out that if they failed to do so ‘I will harry them out of the land, or else do worse.’”

Craig concludes that, “The simplest reading of the evidence is that James called the conference at Hampton Court because that was his usual method of dealing with difficult questions in church and state, and not because he was asked to do it” (pg. 69-70). He may be slightly over-pressing his point in his attempt to re-evaluate the Hampton Court Conference itself, but he at the very least raises concerns about connecting the Conference and the Petition too strongly, and gives clear reason to question the role of the Petition as the solitary cause of the Conference.

The Continuing Relevance Of The Petition

Craig’s proposals do not seem to have yet made much impact in scholarship on the English Reformation or early Stuart politics, if one judges by how often the connection he argues against still gets asserted or assumed. However, even if the casual connection between the Hampton Court Conference and the Millenary Petition is in some doubt (or even severed), it still seems clear that William Barlow alludes to the Petition at several points in his “Sum and Substance,” the semi-official account of the Conference. He describes the four Puritan representatives (Reynolds, Sparkes, Knewstubs, and Chadderton) for example as, “Agents for the Millene Plaintiffs” (Barlow, pg. 2). He also describes how, while Reynolds was making his case to the king, Richard Bancroft, Bishop of London and the arch Anti-Puritan (and shortly thereafter, Archbishop of Canterbury and the major architect of the King James Bible), rudely interrupted him, and knelt down before the king dramatically, begging that no more should be heard from these schismatics. He presented three reasons why. His second reason was;

…that if any of these parties were in the number of the 1,000 Ministers, who had once subscribed to the [Book of Common Prayer], and yet had lately exhibited a Petition to his Majesty against it, they might be removed and not heard, according to the Decree of a very ancient Council, providing, “that no man should be admitted to speak against that, whereunto he had formerly subscribed.”

– Barlow, pg. 26.

This argues that the impact of the Petition was clearly felt at the Conference. Yet it also further supports Craig’s claims. If the Conference had been called to hear the complaints of the Petition, it would hardly make sense to ban anyone from speaking who had signed it! As Craig notes, “These references, which seem to refer to the Humble Petition, show that Barlow and Bancroft considered it the centerpiece of puritan agitation, but not that they thought the conference had been called as a response to it” (Craig, pg. 51). Craig’s argument does not so much sever the connection between the Petition and the Conference as weaken it. Or more specifically, remove its casual elements, urging us to speak in more nuanced ways of the connections. The Petition was still, “the centerpiece of puritan agitation,” which was put on dramatic display at the Conference.

It remains an important window into the exploding controversy between non-conformists and avant-grade conformists that was first publicly showcased at the Conference which conceived the King James Bible, partly as an ultimately failed attempt at bringing uniformity to that controversy. Though it is important to remember that the Petition itself makes no mention of a new translation, which was probably at that point only desired by the King himself, being little more than a gleam in the Puritan eye. It is worthy then of investigation as a source that reveals something about the soon-coming birth of the KJB, and is worthy perhaps of yet one more post (if I try not the reader’s patience) to examine its structure and content.

Posts On The Millenary Petition

The Text Of The Millenary Petition

The Millenary Petition – Its Extant Sources

In our last post, we surveyed the political and religious climate at the coming of King James I to the English throne, and the discontent that led to the presentation to him of the Millenary Petition, properly titled, The Humble Petition of Ministers of the Church of England, Desiring Reformation of Certain Ceremonies and Abuses of the Church. It remains to examine the text of the Petition itself, which we present briefly here, and to explain the requests it made and their impact, which we may do in later posts.

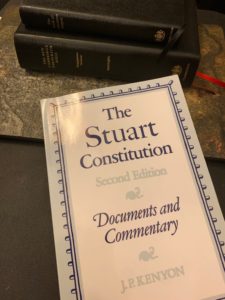

I first came across a copy of the Petition in the source-book of Kenyon (after having ceased looking for it when one misinformed author I read claimed that no extant copy remained). Kenyon cites Thomas Fuller’s The Church History Of Britain, 1648, (reprint of 1837, Vol. III, pg. 193-195) as his source. Roland Greene Usher, in his, The Reconstruction of the English Church, 1910, Vol. I (pg. 290, note 1) noted three different manuscripts of the Petition extant today, variously dated; Add. MSS. 8978 (fol. 107), Add. MSS. 28571 (fol. 175), and, MSS Stowe 180, (fol. 7). None of these is likely to be the original, which no longer remains. (The Wikipedia article on the Petition mistakenly links to an unrelated later petition to Bishop Laud as the original). The form found in Fuller is the most commonly printed. A selectively abbreviated form can also be found in Strype’s, The Life and Acts of John Whitgift. Fuller notes that it likely first occurred in print (as opposed to its manuscript form) when it was printed with the Answer given to it by the Universities in 1603.

I first came across a copy of the Petition in the source-book of Kenyon (after having ceased looking for it when one misinformed author I read claimed that no extant copy remained). Kenyon cites Thomas Fuller’s The Church History Of Britain, 1648, (reprint of 1837, Vol. III, pg. 193-195) as his source. Roland Greene Usher, in his, The Reconstruction of the English Church, 1910, Vol. I (pg. 290, note 1) noted three different manuscripts of the Petition extant today, variously dated; Add. MSS. 8978 (fol. 107), Add. MSS. 28571 (fol. 175), and, MSS Stowe 180, (fol. 7). None of these is likely to be the original, which no longer remains. (The Wikipedia article on the Petition mistakenly links to an unrelated later petition to Bishop Laud as the original). The form found in Fuller is the most commonly printed. A selectively abbreviated form can also be found in Strype’s, The Life and Acts of John Whitgift. Fuller notes that it likely first occurred in print (as opposed to its manuscript form) when it was printed with the Answer given to it by the Universities in 1603.

The standard academic printing is probably now the form in the volume of canons edited by Gerald Bray (pg. 817-819). It is divided by him into smaller enumerated sections which makes it easier to cite each individual petition. The volume is expensive. I reproduce below for later reference the form in Kenyon, whatever differences it may bear from the extant manuscripts or other printings. It is not a critical edition, but is probably the most easily accessible source. (Read the section free at Google Books here).

The Millenary Petition – Its Text

______________________

The humble petition of ministers of the Church of England, desiring reformation of certain ceremonies and abuses of the Church.

To the most Christian and excellent prince, our gracious and dread sovereign, James, by the grace of God, [etc.], We, the ministers of the Church of England that desire reformation, wish a long, prosperous and happy reign over us in this life, and in the next everlasting salvation.

Most gracious and dread sovereign, seeing it hath pleased the Divine Majesty, to the great comfort of all good Christians, to advance your Highness according to your just title, to the peaceable government of this Church and Commonwealth of England; we the ministers of the gospel in this land, neither as factious men affecting a popular parity in the Church, nor as schismatics aiming at the dissolution of the state ecclesiastical; but as the faithful servants of Christ, and loyal subjects of your Majesty, desiring and longing for the redress of divers abuses of the Church, could do no less, in our obedience to God, service to your Majesty, love to his Church, than acquaint your princely Majesty with our particular griefs. For, as your princely pen writeth: ‘The king, as a good physician, must first know what peccant humours his patient naturally is most subject unto, before he can begin his cure.’ And, although divers of us that sue for reformation have formerly, in respect of the times, subscribed to the [Prayer] Book, some upon protestation, some upon exposition given them, some with condition[s], rather than the Church should have been deprived of their labour and ministry; yet now we, to the number of more than a thousand, of your Majesty’s subjects and ministers, all groaning as under a common burden of human rites and ceremonies, do with one joint consent, humble ourselves at your Majesty’s feet to be eased and relieved in this behalf. Our humble suit, then, unto your Majesty is, that [of] these offences following, some may be removed, some amended, some qualified:

I. In the church service. That the cross in baptism, interrogatories ministered to infants, confirmation, as superfluous, may be taken away: baptism not to be ministered by women, and so explained: the cap and surplice not urged: that examination may go before the communion: that it be ministered with a sermon; that divers terms of priests and absolution, and some other used, with the ring in marriage, and other such like in the Book, may be corrected: the longsomeness of service abridged: church-songs and music moderated to better edification: that the Lord’s day be not profaned, the rest upon holy-days not so strictly urged: that there may be a uniformity of doctrine prescribed: no popish opinion to be any more taught or defended: no ministers charged to teach their people to bow at the name of Jesus: that the canonical scripture only be read in the church.

II. Concerning church ministers. That none hereafter be admitted into the ministry but able and sufficient men; and those to preach diligently, and especially upon Lord’s day: that such as be already entered, and cannot preach, may either be removed, and some charitable course taken with them for their relief; or else be forced, according to the value of their livings, to maintain preachers: that non-residency be not permitted: that King Edward’s statute for the lawfulness of ministers’ marriage be revived: that ministers be not urged to subscribe but according to the law to the Articles of Religion, and the King’s Supremacy only.

III. For church-livings and maintenance. That bishops leave their commendams; some holding prebends, some parsonages, some vicarages with their bishoprics: that double-beneficed men be not suffered to hold some two, some three, benefices with cure, and some two, three, or four dignities besides: that impropriations annexed to bishoprics and colleges be demised only to the preachers-incumbents, for the old rent: that the impropriations of layman’s fees may be charged with a sixth or seventh part of the worth, to the maintenance of the preaching minister.

IV. For church-discipline. That the discipline and excommunication may be administered according to Christ’s own institution; or, at the least, that enormities may be redressed: as, namely, that excommunication come not forth under the name of lay persons, chancellors, officials, &c.: that men be not excommunicated for trifIes, and twelve-penny matters: that none be excommunicated without consent of his pastor: that the officers be not suffered to extort unreasonable fees: that none having jurisdiction, or registers’ places, put out the same to farm: that divers popish canons (as for restraint of marriage at certain times) be reversed: that the longsomenes of suits in ecclesiastical courts, which hang sometimes two, three, four, five, six, or seven years, may be restrained: that the oath ex officio, whereby men are forced to accuse themselves, be more sparingly used: that licences for marriage, without banns asked, be more cautiously granted.

These, with such other abuses yet remaining, and practised in the Church of England, we are able to show not to be agreeable to the scriptures, if it shall please your Highness further to hear us, or more at large by writing to be informed, or by conference among the learned to be resolved. And yet we doubt not but that, without any farther process, your Majesty, of whose Christian judgment we have received so good a taste already, is able of yourself to judge the equity of this cause. God, we trust, hath appointed your Highness our physician to heal these diseases. And we say with Mordecai to Esther, ‘Who knoweth, whether you are come to the kingdom for such a time ?’ Thus your Majesty shall do that which, we are persuaded, shall be acceptable to God; honourable to your Majesty in all succeeding ages; profitable to his Church, which shall be thereby increased; comfortable to your ministers, who shall be no more suspended, silenced, disgraced, imprisoned, for men`s traditions; and prejudicial to none, but to those that seek their own quiet, credit and profit in the world. Thus, with all dutiful submission, referring ourselves to your Majesty’s pleasure for your gracious answer, as God shall direct you; we most humbly recommend your Highness to the Divine Majesty; whom we beseech for Christ’s sake to dispose your royal heart to do herein what shall be to his glory, the good of his Church, and your endless comfort.

Your Majesty`s most humble subjects, the ministers of the gospel, that desire not a disorderly innovation, but a due and godly reformation.

– J. P. Kenyon, The Stuart Constitution, 1603-1688: Documents and Commentary, 2nd ed., (Cambridge University Press, 1986), 117–19.

_____________

The Millenary Petition – Its Impact

The various requests made in the Petition provide a window into the past; a snapshot, frozen in time, of the tensions and uncertainties, hopes and fears, that were present when James I took the throne in 1603. They thus form essential background to the Hampton Court Conference where these hopes would rise to their highest point, before being largely dashed. That Conference in turn provides essential background to the King James Bible and its birth.

But how closely connected is the Petition to the Conference? Did the Conference flow out of the Petition as its result? The common answer has always been, “Yes, of course.” Strype for example concluded (or affirmed the consensus) that, “Hence it is evident that this petition gave the occasion to the King to appoint the conference…” One scholar, taking a quite contrary line, has recently answered, “No, not that we can tell.” Thus, in our next post we will examine the impact of the Petition and its connection to the Hampton Court Conference, and ask whether the consensus about their close connection should be challenged.

Posts On The Millenary Petition

The Coming Of King James And The Millenary Petition

James VI of Scotland, who would be forever remembered for the King James Bible, never knew anything but the life of a king, having been crowned shortly after his first birthday in 1567. But Scotland was a kingdom with little power and even less money. When Elizabeth I of England and Ireland died around 3:00 am, Thursday, 24 March 1603, his long and nervous wait for more was finally over.

While official word would not reach him till almost a week later, the secret mission of Robert Carey to inform him brought him assurance of his succession by Saturday. As Teems explains, they had long before worked out a code by which Carey would return to James a blue sapphire ring he had given to Carey’s sister if and when he was to become king. Carey brought the ring with him, and James upon seeing it knew his dreams had come true. He had been proclaimed, “James I, King of England, France, and Ireland, Defender of the Faith.”

Soon preparation began for the procession to London for his coronation; but not too soon of course. It would be bad form and quite tacky to arrive before Elizabeth’s funeral. He didn’t want to appear eager. Or rather, he didn’t want his eagerness to show. Robert Cecil had after all been coaching him via secret correspondence on how to successfully succeed Elizabeth for several years now.

On 25 July 1603, he was crowned King of England at Westminster Abbey, uniting the long-warring kingdoms of Scotland and England for the first time in their history. You can read his acceptance oath in full here. Thomas Tomkins wrote his Be Strong and of a Good Courage to be sung for the coronation, offering a prayer for the monarch derived from Deuteronomy and Joshua. You can listen here. The union of the crowns in a single monarch was a momentous event, even if attendance was curtailed because of the spread of the plague. “It is an historical irony” Jenny Wormald noted (pg. 208-209):

that the two kingdoms were brought together under a Scottish king. It is an even bigger irony that the Scottishness which created so many difficulties should also have had so much to offer the English; for by trying to transmit his Scottish style of kingship to the English throne he defused problems within the church and the state, and thereby presided over a kingdom probably more stable than his predecessor had left, and certainly than his successor was to rule.

Inheriting An England Of Contested Identity

As Diarmaid MacCulloch noted, “When James finally inherited the English throne with remarkably little trouble in 1603, he also inherited a Church of England which had… undergone a contest for its identity.” Of course, outside the official Church but still part of the package deal he inherited in the country, Catholics had long suffered severe persecution in England. Whatever hopes they had of favor from James (and he had likely made them many promises), they were sadly disappointed. Extremist discontent from the fringes soon came to the fore in the famous Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

Within the official Church we might broadly speak of the “Protestants” (a more historically accurate term would be “evangelicals”) that then made up the Church of England. But this was not quite a monolithic group, and factions within it had different attitudes towards what we now refer to as the Elizabethan Settlement. To chart out these factions, and to understand the dreams in the air at the coming of James I, we need first to understand that Settlement and the history that led to it, which means stepping back in time a little further, to the official beginnings of Reformation in England.

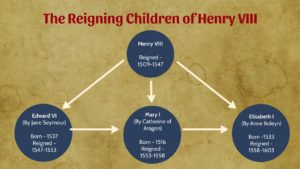

English Reformation?

Technically speaking, Reformation in England began when Henry VIII failed to obtain papal right to divorce (annul his marriage to) Catherine of Aragon (his brother’s widow), whose only living child had been little Mary. She had given the King no male heir to take the throne. Henry had become convinced this was God’s judgment upon an illegal marriage, and it probably helped fuel his ambition that he was in love with and wished to marry the younger Anne Boleyn (who was soon enough pregnant with his daughter Elizabeth). Through a long and complex series of legal maneuvers and Acts of Parliament, Henry rejected papal authority and, essentially, replaced the Pope in England when he was then declared the Supreme Head of the Church of England.

Reformation on the Continent was born out of theology, with a burning conviction about the authority of Scripture and justification by faith at its center. Reformation in England was born, initially at least, out of politics, with a King’s ambitions and burning desire to take a new wife at its center. At that time, in most (not all) other ways, Henry was still a Catholic at heart, who had well earned his title from Pope Leo as, “Defender of the Faith,” for his firm writing against Martin Luther.

The ambiguities and complications stemming from this halting first step meant that more than anywhere else in the world, Reformation in England moved slowly, uncertainly, and by fits and starts. Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell were main drivers along this path of Reformation (as was Anne Boleyn, until Henry tired of her after their brief three year marriage, and had her beheaded for adultery), along which Henry made vacillating progress . But when his nine-year-old son Edward VI was thrust upon the throne upon his death, movement accelerated. One way to observe the progress is to trace the history of a very important book.

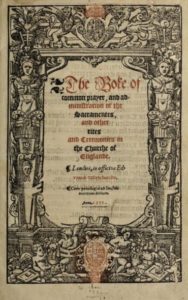

The Book Of Common Prayer

The subtle changes to (and brief revocation of) the Book Of Common Prayer serve as a window into the highly technical religious changes of the roller-coaster of English Reformation. The First English Book Of Common Prayer created by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, who had freedom under Edward VI to implement more of his program of reform, had been designed to replace the highly complex Latin liturgy (patterns of public worship service) of the medieval Western Church, and to severely strip down its ritual. The old liturgy required a number of different books to help the clergy know who was to do what, when. Cranmer’s vision was to reform these patterns into a form more consistent with Protestant principles, in the vernacular tongue. An early step in this program was the 1549 Book Of Common Prayer.

Makeup Of The Book Of Common Prayer