King James Bible History

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut condimentum scelerisque dapibus. Proin eget diam euismod.

The KJV Copyright – A Sordid Tale Of Intrigue And Avarice

- “The KJV is the only Bible that isn’t copyrighted!”

- “Modern Versions are simply a greedy money game!”

- “The KJV is the only Bible that missionaries can make copies of for free!”

- ”The only reason that versions other than the KJV even exists today is because publishers legally have to change a percentage of words in order for a copyright to make money, and modern version publishers only care about money.”

These and similar claims can be found in practically every piece of literature that claims to defend the KJV as the preserved word of God for the English-speaking people. Or just glance around the internet, here, here, here, here, or scores of other places. It seems almost par for the course to claim that the KJV is the “only English Bible not copyrighted” and that all other modern versions are thus inferior to the KJV for this reason. I remember hearing preachers while I was a teen railing about how this was because the KJV represented “God’s words” and all other Bibles were “man’s words.” One cannot copyright “God’s words,” of course. And that’s why the KJV is the only version not copyrighted. In fact, when I’ve taught on the KJV before, lines full of people have assembled, each taking their turn to inform me that I was wrong to suggest that the KJV is not perfect, and the basis for their rebuttal was that clearly I didn’t realize that it is the only English translation not copyrighted. How could I have missed this clear proof that the KJV is perfect? Such a sentiment about copyright is odd both because it would be irrelevant even if it were true, and, more importantly, because it is blatantly false.

An Example From A Trusted Source

R.B. Ouellette wrote what is, in my opinion, one of the best of the books defending the KJV. I respect him, and his work for the gospel, greatly. I quote him here because he’s in a different category than the kind of internet propaganda making such claims that one can find so easily. And I always believe in dealing with the best forms of an argument. That’s why I interacted with his work here, rather than with the scores of “crazies” that would have made easy targets. In fact, we used his book as a required text in Grad School at the Fundamentalist Bible College I attended. Many who defend the KJV are kind, gracious, well-meaning believers who love God. I count many of them my friends. But they often end up repeating the claims of a more radical wing of KJV defenders, without bothering to research whether such claims are true. They typically are not malicious – they simply have neglected their biblical responsibility to “prove all things” (I Thess. 5:19-22). I suspect this is one such example, where otherwise intelligent people are simply repeating absurd claims without bothering to check them out. My guess is that Ouellette is simply repeating here what he has read and assumed true, without really bothering to verify it. Ouellette writes, in a lists of “false statements,” these words about the KJV, “False Statement: The King James Bible is copyrighted,” [Bold original] and then strangely, proceeds to contradict himself and show that his statement is actually not a false one, and that the KJV is in fact copyrighted. He claims that the copyright on the KJV is only to protect the text, and asserts that, “This entire approach is different from the copyrights held today on modern Bible versions. The modern versions are tightly controlled by secular publishing companies for the primary purpose of revenue” (R. B. Ouellette, A More Sure Word, pg. 149). But he is grossly mistaken at almost every point here.

First, as Oullette would construe it at least, Cambridge University Press has a copyright on the KJV (which we will examine below) which produces revenue. His language, intended to be pejorative, sets a double standard. Second, his statement about modern versions being tightly controlled for the primary purpose of revenue is an unforgivable generalization. He cannot see the motives of every publisher. He cannot even see the motives of any publisher. He is not God. Such incredibly sweeping statements are false and unwarranted accusations, being made without multiple evidences provided. Accusations such as this should not be made lightly. Biblically, one should not believe such a statement until documented evidence from every single modern version is produced (see Deut. 19:15). But beyond even these basic problems with his claims, standing behind them lies a serious ignorance of basic facts of history, to which we now turn.

The Greedy Printers Of The KJV

In fact, modern scholars of the KJV, who study the history of the English Bible as a career, generally agree that revenue and profit were major factors in why the KJV became the most widely used version for many years. David Norton and David Daniell have penned some of the most important works on the history of the English Bible to come about in the last several decades (perhaps even the last century). Daniell explains that it was the commercial ability of the KJV to reward its printer that led to its fame;

…contrary to what has been confidently asserted for several centuries, this version [the KJV] was not universally loved from the moment it appeared. Far from it. As a publication in the seventeenth century it was undoubtedly successful: it was heavily used, and it rapidly saw off its chief rival, the three Geneva Bibles, to become the standard British (and American) Bible. But that success was at first for political and commercial reasons, and largely a result of in-fighting between London printers. For its first 150 years, the KJV received a barrage of criticism.

– David Daniell, The Bible In English, hereafter, BIE, pg. 429.

Robert Barker, the King’s printer, held the monopoly on printing Bibles (of any kind). And he incurred some serious money problems. Thus, he needed cash, and cash fast. But the KJV was far easier and cheaper to print than the Geneva Bible that was still the most loved Bible of the people, or the Bishop’s Bible, which was the officially accepted Bible of the clergy. Further, it could be claimed to have been the product of a royal enterprise (whether it was ever officially “authorized” is an open debate among scholars). The revision of the 1602 Bishop’s Bible that had been made in 1611, what we now call the King James Bible, wasn’t really loved more than the Geneva and Bishop’s Bibles. It may not even have been liked by comparison. But it was a great moneymaker, because it was far cheaper to produce and an easier sell. A dirty squabble over who would be able to profit from this cash cow immediately ensued upon its first printing. The details of the first few years are sparse, though Daniell notes, “…the business of the printing of the KJV became almost at once devious, and at times, vicious.” (Daniell, BIE, pg. 451). Serious legal battles, involving preposterous amounts of money, soon ensued. People were jailed, bankrupted, sued, countersued, etc. Daniell pointedly explains,

What was being fought over was the marketing of a new Bible in which interest was high, one that could, in fact, easily be reprinted. The market would be helped by it being said to be a royal enterprise, in a way that no previous English Bible had been. The tight group of spitting enemies, four men and one woman, (Christopher’s wife) were the only people allowed to print the the KJV, and they would be united only in the desire to keep profits as high as they could be…The fighting became total war…

– Daniell, BIE, pg. 455.

When Bookseller Michael Sparke began importing Bibles to avoid paying the high costs, and defeat the monopoly, Robert Barker obtained a warrant to seize these Bibles. Printers who tried to get into the money making scheme had their equipment seized. This ugly “battle for the Bible” continued, but it was, ultimately, a battle for moneymotivated by avarice. Daniell summarizes, noting that the KJV as a new translation, “triumphed because it was commercially manoeuvred to do so, not because it was new. Perhaps enough has been said here to remove the idea of an automatic instant triumph of KJV based entirely on its ‘glorious beauty.'”

[The KJV] triumphed because it was commercially manoeuvred to do so, not because it was new.

– David Daniell

David Norton explains the same reality, sharing further details of the story. He is worth quoting at length here;

David Norton explains the same reality, sharing further details of the story. He is worth quoting at length here;

The last regular edition of the Geneva Bible was published in 1644. Thereafter, to buy a Bible meant to buy a King James Bible. Other versions continued in circulation, but gradually the commercial identity of ‘English Bible’ and ‘King James Bible’ became also a popular identity: with only one major version available, this was inevitable. In spite of the later perception of the KJB’s superiority, this publishing triumph owed nothing to its merits (or Geneva’s demerits) as a scholarly or literary rendering of the originals: economics and politics were the key factors. It was in the very substantial commercial interest of the King’s Printer, who had a monopoly on the text, and the Cambridge University Press, which also claimed the right to print the text, that the KJB should succeed. In the trial of the man principally responsible for suppressing the Geneva Bible, Archbishop Laud, (1573-1645), there is a report that because the KJB, described as ‘the new translation without notes’, was ‘most vendible’, the King’s Printer forbore to print Geneva Bibles for ‘private lucre, not by virtue of any public restraint [and so] they were usually imported from beyond the seas’. ‘Most vendible’ probably means most profitable to the King’s Printer, since Robert Baker had invested substantially in the KJB. The Geneva Bible appeared more marketable, and its continued importation was not just for sectarian reasons but because there was a popular demand.

Norton goes on to cite Laud and his argument that the Geneva was a threat commercially because it was a “better” Bible which could be sold more cheaply, “And would any man buy a worse Bible dearer, that might have a better more cheap?” He picks up the story with Michael Sparke:

The Puritan Michael Sparke, a London bookseller and importer of Bibles in defiance of the monopoly, publisher too of Laud’s opponent William Prynne, gives an identical picture in his attack on printing monopolies… He documents price rises, notes how much cheaper the imported Bibles are, and charges the King’s Printer with commercial exploitation of his monopoly. Like Laud, he writes in several places of the ‘better paper and print’ of the imports. Ironically, then, the KJB’s triumph over its rival came about in part because it was an inferior production: in fair competition it would probably have lost, but its supporters had foul means at their disposal.

– David Norton, A History of the English Bible as Literature, pg. 90-91.

Ironically, then, the KJB’s triumph over its rival came about in part because it was an inferior production: in fair competition it would probably have lost, but its supporters had foul means at their disposal.

– David Norton

One can consult Daniell’s chapter, “Printing the King James Bible,” or Norton’s breathtakingly detailed, “A Textual History Of The King James Bible” for more of the sordid story that makes up this soap opera. Or his two-volume, “History of the Bible as Literature.” Even purchasing his inexpensive condensed volume will give one some of the picture. But for now, it is enough to note that charges that modern publishers of modern versions, with the sole exception of the KJV, are driven by greed and avarice are in fact pointed in exactly the wrong direction. Such accusations are far more true of the printing of the KJV. Scholars of the KJV today agree that the KJV’s ultimate popularity and move from a disliked to a beloved Bible translation was in fact largely due to this greedy profit game.

Are All Modern Versions Really Just The Product Of Greedy Publishers Out For money?

How does the history of the KJV compare to modern versions? Are all modern versions really just a money game? Contrast the story above for example with the NET Bible, which was an endeavor of great cost, but is given “free for all, for all time.” Its intention was to be globally free, something the KJV is not now, and never has been. The editors explain in the preface,

In the second year of bible.org’s ministry (1995) it became clear that a free online Bible would be needed on the bible.org website since copyrighted Bibles can’t be quoted in a huge collection of online studies. The NET Bible project was commissioned to create a faithful Bible translation that could be placed on the Internet, downloaded for free, and used around the world for ministry. The Bible is God’s gift to humanity – it should be free. (Go to www.bible.org and download your free copy.) Permission is available for the NET Bible to be printed royalty-free for organizations like the The Gideon’s International who print and distribute Bibles for charity. The NET Bible (with all the translators’ notes) has also been provided to Wycliffe Bible Translators to assist their field translators. The NET Bible Society is working with other groups and Bible Societies to provide the NET Bible translators’ notes to complement fresh translations in other languages. A Chinese translation team is currently at work on a new translation which incorporates the NET Bible translators’ notes in Chinese, making them available to an additional 1.5 billion people. Parallel projects involving other languages are also in progress.

One can in fact print the entire NET Bible for free, anywhere in the world, and hand it out. One cannot do that in the UK with the KJV (and one could not do that anywhere else in the world, if the British Crown happened to rule the whole world). These godly editors of modern publishing houses (and many others like them) simply do not deserve the accusations of avarice that have been leveled against them by the generalizations of Ouellette and others.

Modern Internet Licenses

But beyond examples like the NET Bible ministry model, and other translations that are intentionally produced for free use, or made freely available, practically every single modern version has provided license to various internet sites to make the entire text of their version entirely free online. The NIV, NKJV, ESV, NET, NASB, HCSB, CSB, RSV, NRSV, GNT, LEB, NLT, The Message, and scores of other modern versions have given away their text digitally for free, despite all the high cost of production, so that the text can be freely accessible to anyone with internet access. Even the German Bible Society’s exorbitantly expensive Nestle-Aland text has been made freely available by the publisher online! Websites like BibleGateway.com, BibleHub.com, BlueletterBible.org, and others, as well as free Apps like YouVersion, make the texts of these versions free to all. In the face of such free access, it is hard to claim, as Ouellette has, that “modern versions are tightly controlled by secular publishing companies for the primary purpose of revenue.”

But besides even that point, as my friend Mark McDonnell has noted, where did anyonone get the idea that a publisher cannot, or should not, charge for their work producing a Bible? That’s not a biblical notion at all. Probably most of us who have a KJV Bible have in fact paid money for it (I’ve spent hundreds on some of my copies!). And Moses, Jesus, and Paul, all explicitly taught that, “The labourer is worthy of his reward,” and has a right to be paid for his work, even those spreading and propagating the very gospel message itself (1 Tim. 5:18, KJV See also Matt. 10:10; Luke 10:7; Lev. 19:13; Deut. 24:15; 1 Cor. 9:4, 7–14).

The KJV And Royal Patents

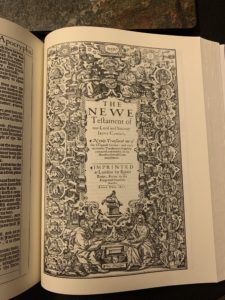

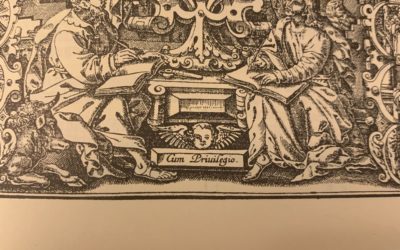

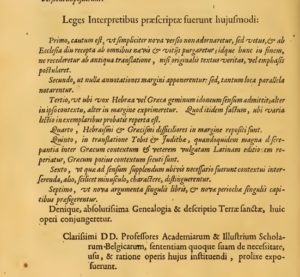

When the KJV was printed, the United States’ Constitution’s “copyright clause” did not yet exist. Copyright Law wasn’t a thing. But that doesn’t mean that pre-cursory rights equivalent to copyright didn’t exist. The first edition of the KJV was printed with the Latin words, “cum privilegio” or “with privilege” at the bottom of its title page for the New Testament (Viewable here, or see the image above). This was the common practice to identify the royal priviligia of printing. The Barkers as royal printers held the printing rights of the Crown or the “Privilege” of printing it, at least initially. And they had a financially beneficial monopoly on printing it. Alister McGrath explains,

The English book trade was regulated by the Stationers’ Company. As printing was permitted only at four centers—London, York, Oxford, and Cambridge—until 1695, regulation of the trade was not especially difficult. The printing of Bibles, however, was seen as a matter of particular importance, and was subject to additional regulations. Since the time of Henry VIII, Bibles printed within England by official sanction—such as Matthew’s Bible, the Great Bible, and the Bishops’ Bible—were subject to a trade monopoly. The monarch granted a “privilege” to favored subjects allowing them a monopoly on the production of certain types of Bible—an honor or favor usually indicated with the words cum privilegio on the title page of the Bible in question. The crown, in turn, received a proportion of the “royalty” paid to the holder of the privilege.

– McGrath, Alister. In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, a Language, and a Culture, pg. 197-198.

He goes on to explain much of the same narrative that Norton and Daniell laid out above, noting that “Barker’s support for biblical translations appears to have been directly proportional to their profitability” (McGrath, p. 198). Ouellette, in his bold attempt to claim the KJV is unique among English Bibles, asserts that, “For the purposes [sic] of protecting the text, the King James Version of the Bible was originally copyrighted and still is in the United Kingdom” (Ouellette, pg. 149). But McGrath rather explains that, “…the use of the King’s Printer for this important new translation did not rest upon any perception that this would ensure a more accurate or reliable printing, but upon the belief that this was potentially a profitable project that would bring financial advantage to Barker and his partners” (McGrath, pg. 199). Costs were cut in every way. Proofreaders were minimized (which led to the numerous, infamous abundance of printing errors, detailed by Norton in the work linked above, like “The Wicked Bible“). And the rights of printing were fought over. Because the KJV was a profitable industry, and printing it was about making money.

The rights of printing it are still today held by the Crown, the same Crown that produced it. It was always, from its first printing in 1611, only allowed to be printed, “with privilege.” The royal patent was extended later to Oxford University Press, and Cambridge University Press. While there has been some vicious back-and-forth over the years, especially in the early years, both of these publishers still hold derived rights to print the KJV. Cambridge explains their royal right of printing (or patent) in what functions as the modern copyright to the KJV, which they have held since the first copy rolled off their presses in 1629. It states;

KING JAMES VERSION

Rights in The Authorized Version of the Bible (King James Bible) in the United Kingdom are vested in the Crown and administered by the Crown’s patentee, Cambridge University Press. The reproduction by any means of the text of the King James Version is permitted to a maximum of five hundred (500) verses for liturgical and non-commercial educational use, provided that the verses quoted neither amount to a complete book of the Bible nor represent 25 per cent or more of the total text of the work in which they are quoted, subject to the following acknowledgement being included:

Scripture quotations from The Authorized (King James) Version. Rights in the Authorized Version in the United Kingdom are vested in the Crown. Reproduced by permission of the Crown’s patentee, Cambridge University Press.

When quotations from the KJV text are used in materials not being made available for sale, such as church bulletins, orders of service, posters, presentation materials, or similar media, a complete copyright notice is not required but the initials KJV must appear at the end of the quotation.

Rights or permission requests (including but not limited to reproduction in commercial publications) that exceed the above guidelines must be directed to the Permissions Department, Cambridge University Press, University Printing House, Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge CB2 8BS, UK (http://www.cambridge.org/about-us/rights permissions/permissions/permissions-requests/) and approved in writing.

(http://www.cambridge.org/bibles/about/rights-and-permissions)

Cambridge Press further explains at their website;

Rights in the Authorized (King James) Version of the Bible and Book of Common Prayer

In the United Kingdom, rights in the Authorized Version of the Bible (AV), also known as the King James Bible or King James Version (KJV), are Crown copyright. Only a small number of publishers have entitlement to reproduce the KJV.

Cambridge University Press is responsible for administering the Crown’s rights in the KJV in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Cambridge first published an edition of the Authorized Version in 1629 and has been publishing it ever since. The Latin term ‘cum privilegio’ is printed on the title pages of Cambridge editions of the KJV and the 1662 Book of Common Prayer (BCP), to denote the charter authority or privilege under which they are published.

There have only ever been at any one time three bodies entitled to print the KJV and BCP in England: the university presses of Cambridge and of Oxford (who similarly have a charter which entitles them to publish and print as a Privileged Press) and the Royal Printer. In addition to its own privilege, Cambridge has also been the owner since 1990 of Royal Letters Patent as The Queen’s Printer: as such, Cambridge is entitled both to print and publish the KJV and the BCP, and also to control or license their publication on behalf of the Crown. The Scottish Bible Board has similar delegated authority in respect of the KJV in Scotland.

The primary function for Cambridge in its role as patent-holder is preserving the integrity of the text, continuing a long-standing tradition and reputation for textual scholarship and accuracy of printing. As a university press, a charitable enterprise devoted to the advancement of learning, Cambridge has no desire to restrict artificially that advancement; commercial restrictiveness through a partial monopoly is no part of our purpose. We grant permission to use the text, and license printing or the importation for sale within the UK, as long as we are assured of acceptable quality and accuracy.

Oxford University Press notes their right, granted by the Crown, to print the KJV;

The University also established its right to print the King James Authorized Version of the Bible in the seventeenth century. This Bible Privilege formed the basis of OUP’s publishing activities throughout the next two centuries.

Copyrights In English Dictionaries

The OED defines “copyright” as “The exclusive right given by law for a certain term of years to an author, composer, designer, etc. (or his assignee), to print, publish, and sell copies of his original work.” For those who strangely prefer it, the Webster’s 1828 English dictionary defines, “Copyright” as,

COPYRIGHT, noun The sole right which an author has in his own original literary compositions; the exclusive right of an author to print, publish and vend his own literary works, for his own benefit; the like right in the hands of an assignee.

The patent or “privilege” that was granted to the KJV on its title page, and is still retained today by Cambridge, fits the definition of a “copyright” as listed in the Webster’s 1828. The KJV is and always has been a copyrighted work.

The KJV – An Un-American Bible?

There is a sense of course in which the KJV can be considered in the “public domain” in the U.S. As noted in legal journals here and here. But it must be noted that this is, historically, simply a function of America at the Revolutionary War choosing to ignore the crown and its laws. As Syn explains (pg. 12 at the above link) “In the United States, after the War of Independence of 1776, English patents were disregarded. This caused the Authorised Version – still protected by royal patents – to enter the public domain outside the United Kingdom.” Cohn likewise explains (pg. 52 at the link above) that, “upon winning the Revolutionary War in 1776, however, the United States disregarded all English patents, and everything under these patents, including the KJV Bible, fell into the public domain. When the Constitution was ratified, all the works in the public domain remained in the public domain.”

Perhaps some have imagined that the KJV was produced in America, and must therefore have an American copyright if that copyright is to mean anything. But it was not produced here, and we didn’t even exists as a nation yet in the age of its production. It is not an American book. Had it been, it would be copyrighted here, and someone would still retain that copyright. The fact that there is no U.S. copyright, and that the copyright is held in the U.K. rather than the U.S. (and is ignored in the U.S.) is a factor of the KJV not being an American production. This does not in any way shape or form make the KJV superior, or point to it alone being the Word of God in English. This doesn’t make the KJV God’s only words in English; it simply makes it un-American in its origins. In fact, its continual stress upon the Divine Right of King’s makes it still today stand in sharp contradiction to the very revolution that birthed America. That is, the KJV is not only not an American Bible in its origins – it could rightly be called an un-American Bible.

A Concluding Comment

Frankly, whether the KJV did or did not have a copyright is a rather irrelevant issue. It has literally nothing to do with the question of whether the KJV is a perfect translation, or a perfect text, or the preserved Word of God for English speaking peoples. But for some reason this issue keeps being brought up by people who think this somehow proves that the KJV alone represents “God’s words.” And this often happens along with slanderous broad-brush accusations being made against modern publishers, many of whom (not all, admittedly) are made up of good and godly men. These good men do not deserve to be so accused and attacked. Slander is sin. Anyone repeating this slanderous accusation should confess and repent of it.

The KJV is, and always has been, held under Copyright.

The KJV is, and always has been, held under copyright. That’s not a bad thing. It just means that the KJV, unlike the NET Bible and a few exceptions noted above, is in this respect like most other English Bibles. It may be a special and unique work. In fact, I think it is, and I often say that I think every English-speaking Christian should own and read a copy of the KJV (though I don’t think anyone should use only a KJV). But it is not unique or special on the basis of some alleged absence of a copyright. Here, it must blend into the crowd of other English versions, and stop pretending to stand head and shoulders above the rest.

The Not-So-Exact King James Bible

Poll a host of English Bible readers, and many of them will assure you that the King James Version is the most literal translation of the Bible into English. It is a more exact translation than every failed contender. The KJV translators, unlike their modern successors, labored assiduously to choose exactly the most accurate word to express in English the words of the original text. In more extreme circles, some even claim that this exactness is such that the translation of the KJV is unassailable, the Translator’s choices for each word guided providentially by the Holy Spirit as he sought to “preserve” His Word into English.

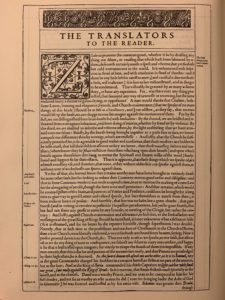

Miles Smith, who served as Translator of the Prophets in the First Oxford Company during Stage 1 of the Creation of the KJV, also drafted the prefatory “The Translators To The Reader” in Stage 3.

But such a passion for exactness on the part of the KJV translators, when history is examined, turns out to be little more than an overblown myth. This is seen both on every page of their translation work, and in their own stated intentions. In their preface, The Translators To The Reader, they defended their work. And they make it plain that carefulness with words was not only not their M.O. – it was a model they eschewed in favor of a much more carefree approach. While Miles Smith was the Translator responsible for penning this work, in what we have referred to as the third stage of the creation of the Translation, he clearly intends to speak with the unified voice of all the Translators here, and we will take his words as such.

The KJV Translators On Why They Rejected Literal Exactness

I have elsewhere examined the overall argument of their preface at great length. We zoom in here on this latter section. I cite here and throughout from the NCPB printing, which is the best I’ve seen. A modern translation of the preface in condensed form is available here.

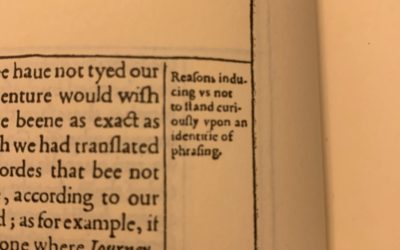

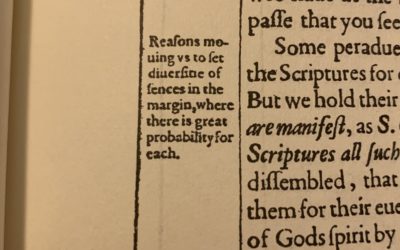

Reasons inducing us not to stand curiously upon an identity of phrasing

Another thing we think good to admonish thee of, gentle reader, that we have not tied ourselves to a uniformity of phrasing, or to an identity of words, as some peradventure would wish that we had done, because they observe that some learned men somewhere have been as exact as they could that way. Truly, that we might not vary from the sense of that which we had translated before, if the word signified the same thing in both places (for there be some words that be not of the same sense everywhere),3 we were especially careful, and made a conscience, according to our duty. But that we should express the same notion in the same particular word, as for example, if we translate the Hebrew or Greek word once by ‘purpose’, never to call it ‘intent’; if one where ‘journeying’, never ‘travelling’; if one where ‘think’, never ‘suppose’; if one where ‘pain’, never ‘ache’; if one where ‘joy’, never ‘gladness’, etc.; thus to mince the matter, we thought to savour more of curiosity than wisdom, and that rather it would breed scorn in the atheist than bring profit to the godly reader. For is the kingdom of God become words or syllables? why should we be in bondage to them if we may be free? use one precisely when we may use another no less fit as commodiously? A godly Father in the primitive time showed himself greatly moved that one of newfangleness called κράββατον, σκίμπους,4 though the difference be little or none; and another reporteth that he was much abused for turning ‘cucurbita’ (to which reading the people had been used) into ‘hedera’.5 Now if this happen in better times, and upon so small occasions, we might justly fear hard censure, if generally we should make verbal and unnecessary changings. We might also be charged (by scoffers) with some unequal dealing towards a great number of good English words. For as it is written of a certain great philosopher, that he should say that those logs were happy that were made images to be worshipped; for their fellows, as good as they, lay for blocks behind the fire: so if we should say, as it were, unto certain words, ‘Stand up higher, have a place in the Bible always’, and to others of like quality, ‘Get ye hence, be banished for ever’, we might be taxed peradventure with St James’s words, namely, ‘To be partial in ourselves and judges of evil thoughts’. Add hereunto that niceness in words6 was always counted the next step to trifling,7 and so was to be curious about names too: also that we cannot follow a better pattern for elocution than God himself; therefore he using divers words in his holy writ, and indifferently for one thing in nature,8 we, if we will not be superstitious, may use the same liberty in our English versions out of Hebrew and Greek, for that copy or store that he hath given us. Lastly, we have on the one side avoided the scrupulosity of the Puritans, who leave the old ecclesiastical words, and betake them to others, as when they put ‘washing’ for ‘baptism’, and ‘Congregation’ in stead of ‘Church’: as also on the other side we have shunned the obscurity of the Papists, in their ‘azymes’, ‘tunic’, ‘rational’, ‘holocausts’, ‘praepuce’, ‘pasche’, and a number of such like whereof their late translation is full, and that of purpose to darken the sense, that since they must needs translate the Bible, yet by the language thereof it may be kept from being understood. But we desire that the Scripture may speak like itself, as in the language of Canaan, that it may be understood even of the very vulgar.

___________

3 Πολύσημα.

4 ‘A bed’. Nicephorus Callistus, Ecclesiastica Historia, 8:42 (PG 146:165).

5 St Jerome, Commentarii in Ionam, 4:6 (CC 76:414; PL 25:1147). See St Augustine, Epistulae, 71:3:5 (PL 33:242).

6 Λεπτολογία.

7 Ἀδολεσχία.

8 Τὸ σπουδάζειν ἐπὶ ὀνόμασι. See Eusebius, Preparation for the Gospel, 12:8:4 (PG 21:968), alluding to Plato, Statesman (Politicus, 261e).

– David Norton, Ed., The New Cambridge Paragraph Bible with the Apocrypha: King James Version, Revised edition, xxxiv–xxxv. Hereafter NCPB.

Under the fifteenth and final heading of their preface, Reasons inducing us not to stand curiously upon an identity of phrasing, the translators explain their second and final specific note about procedure (their first note about procedure related to the use of marginal notes, as we explain here). Two issues are taken up. The first issue here is liberty with words, the bulk of the section. It addresses three aspects of this liberty; lack of consistency in how they render certain words and phrases, then, the partiality they showed to some words, and finally, the diversity of words they did choose. The second issue they take up is their choice to reject both Catholic obscurantism and sectarian (Puritan) innovation.

The First Issue – Shunning Consistency Of Rendering, Or Making, “Verbal And Unnecessary Changings”

To the first issue they note,

Another thing we think good to admonish thee of, gentle reader, that we have not tied ourselves to a uniformity of phrasing, or to an identity of words, as some peradventure would wish that we had done, because they observe that some learned men somewhere have been as exact as they could that way.

– NCPB, xxxiv.

Hugh Broughton And The Theological Case For Literal Translation

They may well have in mind here Hugh Broughton, generally regarded as perhaps the greatest Hebrew scholar of that age. He didn’t end up working on the KJV, (contrary to claims that the KJV companies contained all of the best scholars of the age). He felt that belief in the inspiration and infallibility of Scripture demanded the most literal translation possible. If a Hebrew word or phrase had one meaning, then it should be translated into English only one way, and consistently so throughout the translation. A phrase translated one way in one place should be translated the same way if it occurs in another, unless the intent is different. His concern was deep accuracy to the original text. He set out eight principles of translation in 1597 that he suggested translators should follow, for;

The holy text must be honored, as sound, holy, pure: heed must be taken that the translator neither flow with lies nor have one at all: prophecies spoken in doubtful terms, for sad present occasions, must be cleared by said study and staid safety of ancient warrant: terms of equivocation witty in the speaker for familiar and easy matters, must be looked unto, that a translator draw them not unto foolish & ridiculous senses: Constant memory to translate the same often repeated in the same sort is most needfull.

– Hugh Broughton, An Epistle to the Learned Nobilitie of England...

He was convinced that God had supernaturally preserved every single letter of the Hebrew text in the Masoretic Text (he would later be upset with the KJV translators, presumably partly for how often they emended the Hebrew text with the LXX and Latin Vulgate). The original text must not be trifled with by translators. God cared not only about the sense, and not only about the sentence, but about every single word. God’s text was perfect; “These being matters of Elegancy more than bare necessity, shew that no lesse watchfulness was over the words of sentences. Which thing should move us to hold the text uncorrupt.”

Against those who might maintain (like the KJV translators) that the text had been corrupted and needed restored via textual criticism, Broughton seemed convinced that to say this was to concede to Catholic arguments, “then would the papists earnestly triumph, that we Protestants confess the text to be corrupted: That will I never do, while breath standeth in my breast.” In fact, while the KJV translators would lean most heavily on the 1598 Greek text of Beza, Broughton was convinced Beza and his numerous text-critical notes (which largely shaped the KJV) were an attack on the preservation of the NT text. And to allow the kind of textual criticism that Beza employed was to give in to the Catholics, and to give up the faith altogether;

If the text of the New Testament be corrupt, it can not be from God. But Th. B. [Theodore Beza] spent sixty years to prove that it is most corrupt, & hath full many long speeches to prove that, and triumphet what infinite variety of copies he hath seen, and him you hold your chief…Therefore by this doctrine your New Testament should not be from God: for God would keep that which he gave, as our Hebrew to every yod.”

– Hugh Broughton, A Require of Agreement…1611.

He drew a theological connection between the inspiration and preservation of Scripture, and a literal translation of it. Because of his high views of the perfection of every sentence, word, and even letter of the text, he was passionate that the translator must be exactly literal with the text. He must be consistent in how he renders each word. In his fifth rule for translators, he noted; “The next point that I am to handle, is most pleasant: and the missing in it argueth not want of learning, but of leisure. It containeth constant memory to translate the same often repeated in the same sort: and the differing repetitions likewise with their differences.” Translators who weren’t always literal and consistent in translating the same phrases or words the same way were, for Broughton, traitors to the pure text of Scripture.

The Disagreement Of The KJV Translators

Yet the KJV translators explicitly disagreed. They do note that when their conscience compelled them they would be consistent; “Truly, that we might not vary from the sense of that which we had translated before, if the word signified the same thing in both places (for there be some words that be not of the same sense everywhere), we were especially careful, and made a conscience, according to our duty” (NCPB, xxxiv.). But they simply didn’t feel the need for the kind of literalism with words that Broughton and others were advocating. They felt more liberty than that, and, ” asserted their freedom to use the target language, English, creatively, refusing to be ‘tied’ to any ‘uniformity of phrasing,’” as Wilcox notes.

They provided a few illustrative examples. But they chose as illustrations some of the mildest examples of a class which primarily includes far more extreme instances. Thus, while the heading refers to “phrasing” being varied, and while their practice shows entire sentences rendered differently, their provided examples all relate only to a single wordbeing translated with two different single words. Their actual liberties were much more drastic than this statement might lead us to believe.

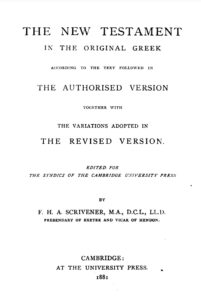

“The Translators To The Reader” serves as the Preface to the KJB.

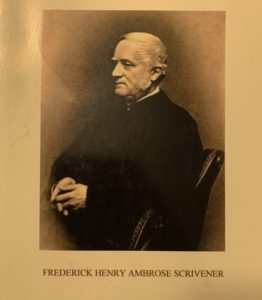

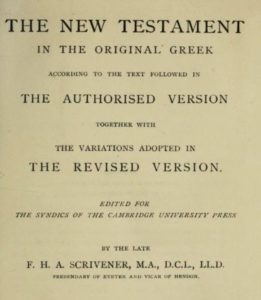

To note one line of evidence, F.H.A. Scrivener counted 8,422 marginal notes in the original 1611 KJV, of which 4,223 provide more literal translations (part of their regular acknowledgement that the text was not as literal as it could be), and 2,738 provide “alternate” translations to those provided in the text. And they are far from noting every such case in the margin. These humble whispers (explained in the prior section of the preface that we don’t cover here, listed out in the full exposition of the preface linked to above) assure us that the translators entertained no notion that the renderings of the KJV were the only accurate ones, or the most exact, or most literal, that could be made.

But that we should express the same notion in the same particular word, as for example, if we translate the Hebrew or Greek word once by ‘purpose’, never to call it ‘intent’; if one where ‘journeying’, never ‘travelling’; if one where ‘think’, never ‘suppose’; if one where ‘pain’, never ‘ache’; if one where ‘joy’, never ‘gladness’, etc.; thus to mince the matter, we thought to savour more of curiosity than wisdom, and that rather it would breed scorn in the atheist than bring profit to the godly reader.

– NCPB, xxxiv.

They believe that to “express the same notion in the same particular word” every time that notion occurs in Scripture would be to “mince the matter.” It would be a scrupulous over-attention to details. In their opinion, this would be to “savor more of curiosity than wisdom,” and such an approach they wholly reject. (The word “curiosity” is an archaic way to refer to scrupulousness.) They are speaking about “pedantry,” or “literalism.” In fact, they feel that to seek such literalism would cause the KJV to be scorned by atheists, and render less help to the Christian reader. They are not tied to uniform phrasing, but rather express the freedom and liberty which they felt with words. They are concerned to communicate the content and ideas of Scripture, not its exact words.

They draw an analogy from Paul’s words about Christian liberty in Romans 14. He argued that the Christian had liberty in issues like Jewish dietary laws. He could keep them or not. Christians shouldn’t fight about them, because we have liberty to do as we please, following only our own consciences. Paul advocated liberty, “for the kingdom of God is not meat and drink; but righteousness, and peace, and joy in the Holy Ghost.” The translators felt a like liberty to render words however they saw fit. No one should argue about precise verbal forms. That’s not the stuff the Kingdom is made of. They defend, “this apparently bold method—potentially tampering with the Word of God—in a series of rhetorical questions” (Wilcox), and so they ask;

For is the kingdom of God become words or syllables? why should we be in bondage to them if we may be free? use one precisely when we may use another no less fit as commodiously?

– NCPB, xxxiv.

Their point of course, as Wilcox explains, is that, “those preparing the new biblical version should not be bound or limited in ways that would reduce the power of the divine word; their text can express spiritual matters and achieve its impact through their exercise of discriminating linguistic taste.” They have and intend to use a greater freedom with language than many would consider appropriate when dealing with the word of God, should precision be the highest goal. But for them, “Mere precision of language is set against the greater value of ‘fit’ words and the choice of ‘commodious’ English vocabulary—that is, those words most likely to profit the reader’s soul.”

Historic Examples When Liberty With Words Caused A Stir

They then provide two examples from church history where liberty with words in translation had caused quite a stir. Their point is to show that the objections against them for not being scrupulously literal are nothing new, and are to be expected. They are well aware that people get somewhat emotionally attached to the Scriptures in a certain verbal form and, as they mentioned earlier, “cannot abide to hear of altering.” They know they will be accused of “meddling with men’s religion” by all the liberties they take with the original text. In the two examples they provide, minor and insignificant verbal changes had caused a stir. The stir about their even greater liberty with words is thus to be expected.

First comes an example from a Bishop Triphyllius in the late IV century, who had substituted a different word in an exposition of Mark 2:9. The phrase “take up thy bed and walk,” using the word krabbaton for bed, had apparently been presented in an exposition using instead the word skimpous for bed. They have a slightly different nuance, but the same basic meaning. However, according to the story as recounted in Nicephorus, St. Spyridon had harshly rebuked the Bishop for not being exact with the words of Scripture. Or, in the words of the translators, “A godly Father in the Primitive time showed himself greatly moved, that one of newfangledness called krabbaton, skimpous, though the difference be little or none…” They regard the rebuke of St. Spyridon as unnecessary.

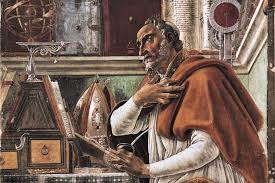

Second comes a more well known example from the Latin Vulgate of Jerome. The translators refer in the margin both to a text in Jerome’s commentary on Jonah that mentions the incident and to Augustine’s epistle to Jerome which recounts it. The Old Latin texts, translated from the Greek LXX, had apparently used the word “cucurbita” or “gourd” for the description of the plant in the text in Jonah 4:6. But when Jerome produced his revision of the Latin, going back to the Hebrew, he had determined that the Hebrew word more properly was hedera or “ivy.” Augustine had described the situation in his letter to Jerome;

St. Augustine, by Sandro Botticelli.

“A certain bishop, one of our brethren, having introduced in the church over which he presides the reading of your version, came upon a word in the book of the prophet Jonah, of which you have given a very different rendering from that which had been of old familiar to the senses and memory of all the worshippers, and had been chanted for so many generations in the church. Thereupon arose such a tumult in the congregation, especially among the Greeks, correcting what had been read, and denouncing the translation as false, that the bishop was compelled to ask the testimony of the Jewish residents (it was in the town of Oea). These, whether from ignorance or from spite, answered that the words in the Hebrew manuscripts were correctly rendered in the Greek version, and in the Latin one taken from it. What further need I say? The man was compelled to correct your version in that passage as if it had been falsely translated, as he desired not to be left without a congregation,—a calamity which he narrowly escaped.”

– Augustine, Epistle 71.3.5

Or, in the translators’ words, “…and another reporteth, that he was much abused for turning Cucurbita (to which reading the people had been used) into Hedera.” They conclude that their own “verbal and unnecessary changings” will of course meet similar opposition, “Now if this happen in better times, and upon so small occasions, we might justly fear hard censure, if generally we should make verbal and unnecessary changings.” This is what they claimed to have done. They have changed the words of the text in places where change was not needed. And they are aware that some will oppose this. David Norton, expert historian of early English Bibles, explains that, “In this the translators were following the example of their predecessors and also reflecting a certain looseness in the spirit of the age. Variety of translation is at one with the tendency to inconsistent phrasing of quotations from the Bible evident in the preface itself and in a number of seventeenth-century writers.” But as he notes, “a large number of scholars came to think, with Broughton, that inconsistency was a mistake. The preface to the RV NT calls it ‘one of the blemishes’ in the KJB, and the RV followed the opposite policy.” He goes on to provide an illuminating example;

An example will help to demonstrate this. One of the KJB’s most famous lines, ‘consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they toil not, neither do they spin’ (Matt. 6:28), is also rendered, ‘consider the lilies how they grow: they toil not, they spin not’ (Luke 12:27). The second version is little known and inferior as English. As translations, they render different Greek verbs with the same English word, ‘consider’. The first variation (‘lilies of the field’, ‘lilies’) exactly reflects a difference in the Greek: the resonant phrase exists because of literal translation. The last part of the sentence is identical in the Greek of both gospels… but the KJB in one instance produces the memorable cadence of ‘they toil not, neither do they spin’ and in the other more accurately reflects the structure of the Greek in the staccato pair of parallel phrases, ‘they toil not, they spin not’. Thus three aspects of the KJB translators’ work can be seen in this one example: failure to distinguish between different words in the original, literal translation happily producing a phrase of memorable quality, and varying translations in one case producing another such phrase. There is no way of knowing if the last variations were produced for literary reasons, or even, if they were, which version the translators actually considered the better: they could have argued for the parallelism of Luke’s version.

The fact that the translators deliberately adopted this policy of inconsistency (even if only because of precedent) is the only evidence that shows a sense of responsibility towards the English language. However, the passage from the preface does not show genuinely literary motives, even if it lays open the way for choice of vocabulary on literary grounds. The concern is still with precision. ‘Fit’, as has been shown, does not carry aesthetic connotations, and ‘commodiously’ is used in the sense of usefully or beneficially for conveying sense. A similar point is made by Ward Allen about the final phrase quoted: ‘by niceness Dr Smith means the domination of thought by words rather than the domination of words by thought, or exactness’ (Translating for King James, p. 12).

– Norton, David, A History Of The English Bible As Literature, pp. 68-69.

Some Examples Of Liberty With Words

It may be instructive to examine a few examples from their work of what they mean by the “verbal and unnecessary changings” which they have made (I am indebted to Bishop Ellicott for many of these examples);

OT Passages Rendered Inconsistently In The NT

Many examples could be provided here. Gen. 15:6 is quoted (probably from the LXX) three different times in the NT (Rom. 4:3; Gal. 3:6; James 2:23), always with identical wording (only the word order differs). But each time, the translators have slightly varied the way they translated it;

– “Abraham believed God, and it was imputed unto him for righteousness.” (Jam 2:23)

– “Abraham believed God, and it was accounted to him for righteousness.” (Gal 3:6)

– “Abraham believed God, and it was counted unto him for righteousness.” (Rom 4:3)

Deut. 32:35 is quoted twice in the NT (Rom. 12:19; Heb. 10:30), probably from the LXX, (the form is different still from the Hebrew MT, and the KJV translation of it), both times in the same words in the Greek text, but rendered differently both times in KJV;

– “For we know him that hath said, Vengeance belongeth unto me, I will recompense, saith the Lord.” (Heb 10:30, KJV)

– “For it is written, Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord.” (Rom 12:19, KJV)

Psalm 95:11 is quoted (from the LXX) by the author of Hebrews twice, and the text is verbally identical both times (3:11 and 4:3). But the translators made the choice to render the same quotation in two different ways.

– “So I sware in my wrath, They shall not enter into my rest.” (Heb 3:11, KJV)

– “As I have sworn in my wrath, if they shall enter into my rest…” (Heb 4:3, KJV)

The English reader who does not understand the liberty they have taken with words might think these quotation to have occurred in two different forms. Yet this is not the case. When KJVO folks challenge me to prove “even one error of translation in the KJV” I usually point them to these two passages. We have here exactly the same Greek text, yet KJV translators translated the exact same text in two totally different ways in two different passages. Nor could one claim that different authors are interpreting the text in two different ways, for the author and context is identical. Since the KJV renders both passages differently, if literal and exact translation is the standard of measure, then they are undeniably mistaken in at least one of these translations.

Intentionally Repetitious Language Rendered Variously

Numerous such passages exists. In Rom. 4, the same Greek lemma for “accounting” occurs 11 times, meaning the same thing in each case. Paul intends the repetition to show that the same “counting” that was given to Abraham is given to all who come to Christ by faith. But the translators chose three different words variously to translate it with here; sometimes as “counted,” other times, “reckoned,” others, “imputed.” Paul’s point is to build the connections between his use of the word – consistency is important to his meaning. Yet the English reader who was unaware of their liberties might think there to be three different Greek words here, and thus miss the connections Paul is making.

In Rom. 7:7-8, the verb for “covet” and its noun form is repeated by Paul to make a point. Yet it is translated variously as “lust,” “covet,” and “concupiscence” by the translators, ignoring the fact that it has the same meaning in each place. They have created variety where Paul intended to create repetition. The reader who was unaware of their liberties with words, or who took the words of their translation too seriously, might easily miss Paul here.

In I Cor. 3:17, Paul uses a play on words when he writes, “If any man destroy the temple of God, him shall God destroy,” using the same word twice. He even arranges the words next to each other in the sentence to highlight his wordplay. But the translators translated the first as “defile” and the second as “destroy.” Inconsistency is created where Paul intended consistency to make a point.

Throughout II Cor. 1 the pair of words for “comfort” and “affliction” are intentionally repeated and paired against each other numerous times by Paul. Yet the translators variously render these same two words as, “comfort,” “affliction,” “tribulation,” and “consolation” in the passage, creating variety where there was none in the original, and losing Paul’s rhetorical impact.

Mark used the adverb “immediately” some 42 times throughout his gospel, connecting the various narratives with a consistently vivid pace. But what Mark in most cases intends as a regular literary device, the KJV’s liberty with words has obliterated. It varies the translation of Mark’s adverb by variously translating with;

– “immediately” (commonly)

– “straightway” (Mk. 1:10, 18, 20-21; 2:2; 3:6; 5:29, 42; 6:25, 45, 54; 7:35; 8:10; 9:15, 20, 24; 11:3; 14:45; 15:1)

– “forthwith” (Mk. 1:29, 43; 5:13)

– “anon” (Mk. 1:30)

– “as soon as” (Mk. 1:42; 5:36; 11:2; 14:45)

The English reader unaware of the liberty with words that the translators took could easily miss Mark’s intentional repetition of the same word for literary effect. They have created a variety that the original text simply did not have.

Identical Gospel Parallels Rendered Inconsistently

One might also note parallel passages that occur in the gospels, where the wording between the Evangelists is identical in Greek, but where the KJV has translated the texts differently. These might give the mistaken impression to the English reader of greater variance between the gospels than actually exists in the Greek text being translated. A few examples (from hundreds) make the point;

– Mt. 4:6/Luke 4:10 – concerning/over

– Mark 1:17/ Matt. 4:19 – follow/ come ye after

– Matt. 10:14/Luke 9:5 – the dust/the very dust

– Matt. 10:22/ Mark 13:13 – he that endureth to the end shall be saved/he that shall endure the same shall be saved

– Matt. 17:19/Mark 9:28 – apart/privately

Various Other Inconsistencies

Consider the one Hebrew word sometimes translated, “face.” Strong’s lexicon lists only two basic definitions for the word with a variety of applications of those definitions;

(1) “The face (as the part that turns); used in a great variety of applications (literally and figuratively)”

(2) “also (with prepositional prefix) as a preposition (before, etc.)”

Modern lexicons like HALOT, with slightly more scholarly nuance, list some 15 basic meanings, with slight distinction among each. Yet this one word was rendered some 83 different ways by the KJV translators. Surely, in so many instances of this word in the Hebrew Bible, it has several different meanings, and good translation respects this. But there are clearly not eighty-three distinctly different meanings of the word. The English reader who wasn’t aware of the translator’s liberty with words might easily think some eighty different words to occur in the original text. But he would be mistaken. This is rather another instance of their taking liberty with words. We could raise a similar point with the example of the Hebrew word for “hand.”

Or, from another direction, there are some 45 distinctly different Hebrew and Aramaic words, (and around 12 different Greek words) that are simply rendered with the single English word “destroy” in the KJV (see a full list here). This failure to be more precise obliterates the various nuances and distinctions that the original language texts employed between these words. Yet in other passages, the translators have used some 80 different English expressions to render these same Hebrew and Aramaic roots, so it is not as if they didn’t have a store of English words to present the distinctions of the original with. They were creating what they called, “verbal and unnecessary changings.” The English reader who didn’t understand the liberty they took with words might think every occurrence of “destroy” in its different forms to have meant the same thing to the original readers. But this would not be the case.

The Greek word elpis occurs fifty-four times in the Greek text of the KJV NT. It is rendered, “hope” fifty-three times. Yet in Heb. 10:23, it is inexplicably (mis)translated, “faith” (against all earlier English translations, and against all lexical sense). This is so absurdly inconsistent that it is usually concluded to be simply a printing mistake never corrected in the KJV (except in Scrivener’s CPB edition). But Norton in the NCPB retains the reading of the 1611 edition (“faith”) noting;

This could be a printer’s error because of ‘faithfull’ later in the verse, but the 1611 reading has been accepted by most editors.

Whether an accidental error that remains uncorrected in the KJV, or another example of their “liberty,” it nonetheless reflects their inexactness, which changes the meaning of the author’s text.

Gerald Hammond demonstrates at length that the KJV was far more consistent in such linguistic issues than the English translations that came before it (though less consistent than those that came after it). In fact he ultimately concludes that the KJV’s consistency of style is “why it kept so powerful a hold over English minds for the next three hundred and fifty years” (Gerald Hammond, The Making Of The English Bible, pg. 233). But even in a work positing such a bold thesis, he qualifies that, “We should not assume that the translators aimed for complete consistency” (pg. 199), noting that, “The Authorized Version makes no special attempt to maintain a complete consistency of rendering where one English word is, wherever contextually possible, used to translate one particular Hebrew word.” (pg. 201-202).

In each of these cases, and thousands more that we could list, it becomes clear that the KJV translators did not feel tied to a particular verbal form for their translation. They did not seek to be verbally exact or verbally consistent in their translation. They explained this from the very start so that no one would take the words of their translation too seriously. As Alister McGrath explains;

The translators also avoided what—at least, to them—seemed a wooden and dogmatic approach to translation, which dictated that precisely the same English words should regularly be used to translate Greek or Hebrew words. The preface sets out clearly the view that the translators saw themselves as free to use a variety of English terms…

This principle suggests that the translators saw variety as a means of enhancing the beauty of the text, by avoiding crude verbal repetitions. Yet it must be pointed out that this principle led to some quite puzzling consequences. The translation of Romans 5:2–11 reveals this concern to ensure variety. According to the King James Bible, Paul and his colleagues “rejoice in hope of the glory of God… we glory in tribulations… we also joy in God.” The same Greek verb—which would normally be translated as “rejoice”—is, in fact, being translated using different words (here italicized) in each of the three cases. There can be no doubt that this flexibility allowed the translators to achieve a judicious verbal balance that enhanced the attractiveness of the resulting work. Yet inevitably a price was paid for this in terms of the accuracy that some had hoped for.

– McGrath, Alister. In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, a Language, and a Culture, pp. 193-194.

Election And Reprobation Of Language – “Unequal Dealings” With Words

Having explained their intention to make “verbal and unnecessary changings” they then take up in the preface the second issue in their liberty with words; the reason they often chose one English word or phrase but rejected another. Using an interesting analogy from a philosopher’s comment, they build a vivid picture. Imagining a forest of trees, the philosopher reflects on the fact that some of these trees will be shaped into idols by pagans to worship. But ironically, some of these very same trees will be turned into firewood to be burned. In a somewhat arbitrary choice, some trees have a destiny as worthless as firewood, and other of the exact same trees have a destiny as an object of worship. The translators draw an analogy to their sometimes arbitrary choice of one word over another. Perhaps from the doctrine of election, the translators suggest that they have been quite partial in “electing” some words to become part of biblical language, and “damning others” to remain only part of the common but not biblical vocabulary. They conclude by quoting James and asserting themselves as judges of words;

We might also be charged (by scoffers) with some unequal dealing towards a great number of good English words. For as it is written of a certain great philosopher, that he should say that those logs were happy that were made images to be worshipped; for their fellows, as good as they, lay for blocks behind the fire: so if we should say, as it were, unto certain words, ‘Stand up higher, have a place in the Bible always’, and to others of like quality, ‘Get ye hence, be banished for ever’, we might be taxed peradventure with St James’s words, namely, ‘To be partial in ourselves and judges of evil thoughts’.

– NCPB, xxxiv.

Freedom In Wording – Rejecting “Niceness In Words”

In the third aspect of the liberty they have taken with words, they point out the abundant store of linguistic vocabulary that has been furnished for them by God in English, and even the pattern He has set by varying in Scripture the language He uses to describe things, with an apparent indifference (they think) to the exact wording. In rejecting a focus on words that they consider, “trifling,” they believe they are actually following God’s example;

Add hereunto that niceness in words was always counted the next step to trifling, and so was to be curious about names too: also that we cannot follow a better pattern for elocution than God himself; therefore he using divers words in his holy writ, and indifferently for one thing in nature, we, if we will not be superstitious, may use the same liberty in our English versions out of Hebrew and Greek, for that copy or store that he hath given us.

– NCPB, xxxiv.

Thus, in this section dealing with their desire to “use the same liberty in our English versions” and to not tie themselves to a “uniformity of phrasing,” they have made it clear that they feel free to make “verbal and unnecessary changings.” They are “admonishing” the reader to be careful not to focus too much on the precise words of their translation; they certainly did not. They are more concerned with the message than the exact verbal form. They are not bound by exactness of words, and they don’t want the reader to be either.

For is the kingdom of God become words or syllables? why should we be in bondage to them if we may be free, use one precisely when we may use another no less fit, as commodiously?

– KJV Translators

The Second Issue – Creating A Vulgar Version, Or, Speaking in “The Language Of Canaan”

After explaining in three parts their liberty with words, they then take up briefly the second issue concerning their handling of words, which is the balance they sought between traditionalism and obscurantism. They sought to stand between tradition and innovation. For the most part, their translation will retain traditional and familiar language, eschewing any innovation, and trodding the already the well-worn verbal paths of prior English versions. But there are other ways in which they will blaze new trails with their work.

This Bible was new and at the same time not new, presented as the sacred word for the future and yet full of deliberate archaisms and links with previous versions. The KJB’s compromise between the given past and the ordained future may be seen in the detail of the revisers’ choices: the voices of Tyndale and Coverdale, the tones of the Roman Catholic Douai Bible, and phrases of the Protestant Geneva Bible are all to be heard within the verbal echo-chamber of the KJB, yet it has its own distinctive cadence and blend of vocabulary, particularly in areas of Jacobean theological controversy such as priesthood and the church. Ironically yet typically, the engraved title-page of the New Testament in the KJB is actually borrowed from the last edition of the old Bishops’ Bible (1602), asserting visually as well as verbally the new Bible’s acknowledged line of inheritance.

– Wilcox, The KJB In Its Cultural Moment

KJV NT title page, repurposing a woodcut from the 1602 Bishops Bible.

We won’t examine this section of the preface in detail here, though it is worth noting. They rightly understood that these are two sides of the same issue, and that wise translation should seek a medium between the two. Translation should be into the vulgar tongue, or the language of the common man. The goal should be to make the Bible understood. But a translator can find a ditch on either side, becoming either too novel or too obscure. All translation seeks to lessen the distance between the modern reader and the original one. Yet in our attempt to speak a contemporary word, we dare not speak a faddish one. They shun both what they consider sectarian (that is, Puritan) novelty, and Catholic obscurantism. They would rather avoid both extremes, and speak instead the language of the common man.

Lastly, we have on the one side avoided the scrupulosity of the Puritans, who leave the old ecclesiastical words, and betake them to others, as when they put ‘washing’ for ‘baptism’, and ‘Congregation’ in stead of ‘Church’: as also on the other side we have shunned the obscurity of the Papists, in their ‘azymes’, ‘tunic’, ‘rational’, ‘holocausts’, ‘praepuce’, ‘pasche’, and a number of such like whereof their late translation is full, and that of purpose to darken the sense, that since they must needs translate the Bible, yet by the language thereof it may be kept from being understood. But we desire that the Scripture may speak like itself, as in the language of Canaan, that it may be understood even of the very vulgar.

– NCPB, pg. xxxiv–xxxv.

As Mark Ward has noted at length in “Authorized,” (and Noah Webster in his own work cited at that link), their translation today, however valuable, can no longer accomplish this, their ultimate stated goal in translation. Indeed, as I note in my review at that link, they probably missed that mark the very first and only time they drew their bow, however carefully they may have aimed for it.

Advocates for Literal Translation, Modern And Ancient

Contrary to what is sometimes alleged, the KJV does not represent a perfectly “literal” translation of the text with unflinching exactness. And this is not some accident, mistake, or failure on the part of the translators. Rather, the inconsistency of rendering was a stated intention of the KJV translators who took great liberty with words. Anyone who wants to insists today that every single word of the KJV represents exactly the way it “should” be rendered in English, or wants to argue about the exact phrasing or wording of the KJV will find the greatest objectors to be the Translators themselves. They would no doubt be saddened by those who have made the kingdom of God into words and syllables, and who have taken their words so seriously.

Contrary to what is sometimes alleged, the KJV does not represent a perfectly ‘literal’ translation of the text with unflinching exactness.

But if someone does oppose translators taking this kind of liberty with the text in translation, it is informative to note that some translations today do not take such license. The ESV, for example, in its passion for what its translation committee refers to as “essentially literal” translation, has rejected the precedent of liberty set by the KJV here. In their preface they explain;

The ESV is an “essentially literal” translation that seeks as far as possible to reproduce the precise wording of the original text and the personal style of each Bible writer….Every translation is at many points a trade-off between literal precision and readability, between “formal equivalence” in expression and “functional equivalence” in communication, and the ESV is no exception. Within this framework we have sought to be “as literal as possible” while maintaining clarity of expression and literary excellence. Therefore, to the extent that plain English permits and the meaning in each case allows, we have sought to use the same English word for important recurring words in the original; and, as far as grammar and syntax allow, we have rendered Old Testament passages cited in the New in ways that show their correspondence. Thus in each of these areas, as well as throughout the Bible as a whole, we have sought to capture all the echoes and overtones of meaning that are so abundantly present in the original texts.

Leland Ryken notes that this is one of the clearest differences between the KJV and the ESV. To be sure, the register of the English style, and the text-critical differences between the Greek text of the KJV and the Greek text of the ESV create the largest amount of what little difference there is between the two versions. But if one sets the text-critical advances behind the ESV to the side, it is the consistency of the ESV that appears as the starkest difference between the KJV and ESV;

The most obvious difference between the KJV and the ESV centers on the issue known today as concordance. Concordance in this case means using the same English word for a given Hebrew or Greek word every time (or nearly every time) it occurs in the Bible. Concordance was a high priority for the ESV translators. This was inevitable because of the commitment to verbal equivalence. The King James translators did their work at a moment in history when the English language was expanding at an unprecedented rate and when excitement about the burgeoning possibilities of language ran high. It was a time of lexical and linguistic exhilaration. This is the context for the famous statement about synonyms that appears in the preface to the KJV: [He then cites the passage we quoted above.] The decision to multiply synonyms reflects Renaissance exuberance over words and is not governed by fidelity to the biblical text. It is my impression that the decision of the King James translators to provide variety rather than consonance for a given Hebrew or English word makes the KJV a less literal translation.

The ESV parts company with the KJV on this issue. The goal of the translators was to maintain as much concordance as possible (only occasionally departing from it). The preface states, ‘We have sought to use the same English word for important recurring words in the original.’

There is a complex additional dimension to concordance, namely, making New Testament quotations from the Old Testament as parallel as the original text allows. The ESV translators strove for concordance on this matter also. In the words of the preface, “As far as grammar and syntax allow, we have rendered Old Testament passages cited in the New in ways that show their correspondence.

– Ryken, Leland. The ESV and the English Bible Legacy, pp. 103-104.

Whether Ryken and his translation philosophy is the best one is not the point here. That is a hotly contested issue in translation today. The point here is that if one believes that the most literal translation is automatically the besttranslation, then the ESV seems to have an upper hand over the KJV. In fact, every single one of the examples of inconsistency I’ve listed above, (and thousands of others I’ve not mentioned) is corrected in the ESV. Claims that the KJV is the “most literal” or “the most exact” are simply not accurate. In fact, this is a moniker that should go to an interlinear text rather than a translation to begin with. Beyond that, it should certainly go to woodenly literal translations like the Young’s Literal Translation of the TR, or at best works like the NASB, before it would go to the KJV. Broughton would be proud.

Personally, I am of the opinion that while literal translation has a distinctly important place in English Bible translation, we lose the value of a different kind of accuracy when we prioritize a literal approach over a more functional approach. We should value both. As NT Wright has well noted,

There are at least two sorts of accuracy. The first sort, which a good Lexicon will assist, is the technical accuracy of making sure that every possible nuance of every word, phrase, sentence and paragraph has been rendered into the new language. But there is a second sort of accuracy, perhaps deeper than this: the accuracy of flavour and feel. It is possible, in translation as in life, to gain the whole world and lose your own soul – to render everything with a wooden, clunky, lifeless ‘accuracy’ from which the one thing that really matters has somehow escaped, producing a gilded cage from which the precious bird has flown. Such translations – the remarkable Revised Version of the 1880s might be one such [he later lists an example from the KJV as another] – are of considerable use to the student who wants to get close to the original words. They are of far less use to the ordinary Bible reader who wants to be grasped by the actual message of the text.

– NT Wright, The Monarchs and the Message.

This is one reason why I don’t think anyone should only use the KJV, or only use any one translation. The wisest Bible readers read from different translations that come from opposing ends of the spectrum. But for those who prioritize literal translation, hopefully this note has shown that the KJV does not automatically hold the position of being most faithful to a literal translation philosophy.

Of course, modern scholars like Ryken are not the only ones who oppose the carefree approach of the KJV. As we noted above, Hugh Broughton had been advocating for a decade before the birth of the KJV that a translator must be literal and consistent. He wrote a letter to the translators during their work to provide them more advice. Norton summarizes;

It was perhaps his last attempt to influence the KJB, if only by opening the way for post-publication criticism… ‘We should’, he continues, ‘by common consent, for near tongues, express this variety, that the holy eloquence should not be transformed into barbarousness. By right dealing herein, great light and delight would be increased. The Hebrew would be in honour among all men when the inimitable style should be known how it expressed Adam’s wit’ (Works, III: 702). At the back of this lies an equation between literal translation and eloquence in translation: the translation would be eloquent not as English but as Hebrew and Greek in English….

Much of Broughton’s work was ignored. But however little the KJB translators responded to its detail, it contributed significantly to the intellectual atmosphere of the time by encouraging a reverence for the eloquence of the original without arguing for an equivalent eloquence in English, but above all by demanding the whole truth and arguing that it could only be revealed through the closest attention to the words and syllables of the perfect originals.

– Norton, David. A History, Page 60.

But the KJV translators shared neither Broughton’s view of the perfection of the original text, nor his conviction that such a view of the Bible required a meticulous consistency in rendering. And so they pressed on in the employment of their more carefree principles.