Poll a host of English Bible readers, and many of them will assure you that the King James Version is the most literal translation of the Bible into English. It is a more exact translation than every failed contender. The KJV translators, unlike their modern successors, labored assiduously to choose exactly the most accurate word to express in English the words of the original text. In more extreme circles, some even claim that this exactness is such that the translation of the KJV is unassailable, the Translator’s choices for each word guided providentially by the Holy Spirit as he sought to “preserve” His Word into English.

Miles Smith, who served as Translator of the Prophets in the First Oxford Company during Stage 1 of the Creation of the KJV, also drafted the prefatory “The Translators To The Reader” in Stage 3.

But such a passion for exactness on the part of the KJV translators, when history is examined, turns out to be little more than an overblown myth. This is seen both on every page of their translation work, and in their own stated intentions. In their preface, The Translators To The Reader, they defended their work. And they make it plain that carefulness with words was not only not their M.O. – it was a model they eschewed in favor of a much more carefree approach. While Miles Smith was the Translator responsible for penning this work, in what we have referred to as the third stage of the creation of the Translation, he clearly intends to speak with the unified voice of all the Translators here, and we will take his words as such.

The KJV Translators On Why They Rejected Literal Exactness

I have elsewhere examined the overall argument of their preface at great length. We zoom in here on this latter section. I cite here and throughout from the NCPB printing, which is the best I’ve seen. A modern translation of the preface in condensed form is available here.

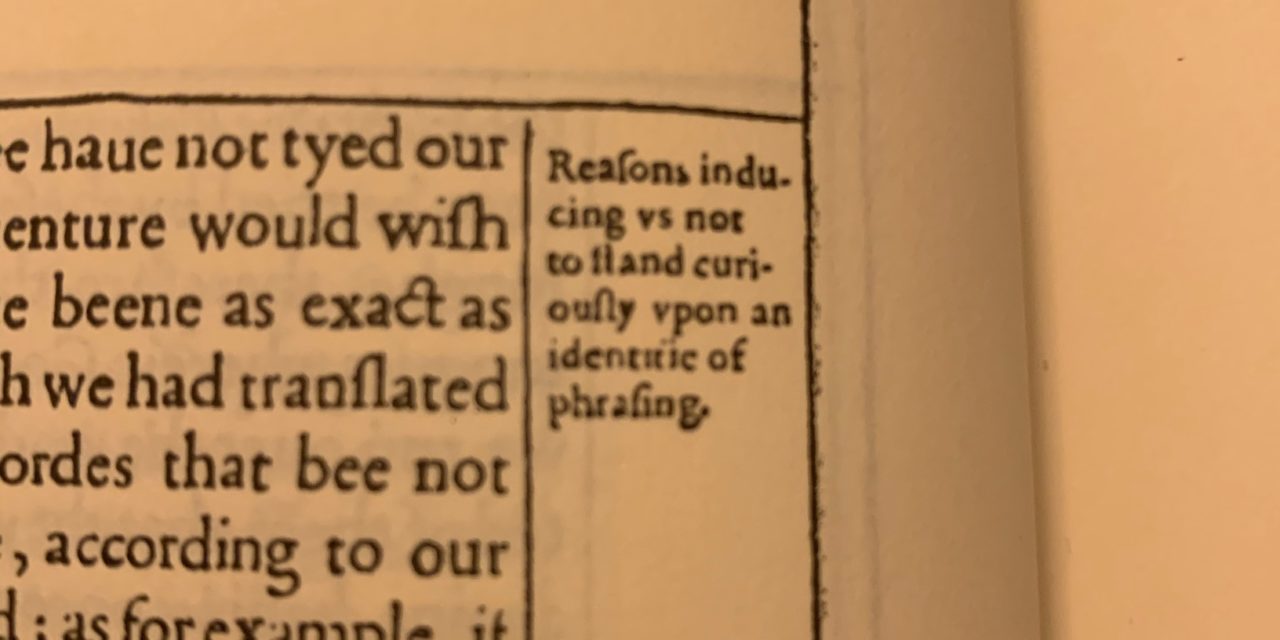

Reasons inducing us not to stand curiously upon an identity of phrasing

Another thing we think good to admonish thee of, gentle reader, that we have not tied ourselves to a uniformity of phrasing, or to an identity of words, as some peradventure would wish that we had done, because they observe that some learned men somewhere have been as exact as they could that way. Truly, that we might not vary from the sense of that which we had translated before, if the word signified the same thing in both places (for there be some words that be not of the same sense everywhere),3 we were especially careful, and made a conscience, according to our duty. But that we should express the same notion in the same particular word, as for example, if we translate the Hebrew or Greek word once by ‘purpose’, never to call it ‘intent’; if one where ‘journeying’, never ‘travelling’; if one where ‘think’, never ‘suppose’; if one where ‘pain’, never ‘ache’; if one where ‘joy’, never ‘gladness’, etc.; thus to mince the matter, we thought to savour more of curiosity than wisdom, and that rather it would breed scorn in the atheist than bring profit to the godly reader. For is the kingdom of God become words or syllables? why should we be in bondage to them if we may be free? use one precisely when we may use another no less fit as commodiously? A godly Father in the primitive time showed himself greatly moved that one of newfangleness called κράββατον, σκίμπους,4 though the difference be little or none; and another reporteth that he was much abused for turning ‘cucurbita’ (to which reading the people had been used) into ‘hedera’.5 Now if this happen in better times, and upon so small occasions, we might justly fear hard censure, if generally we should make verbal and unnecessary changings. We might also be charged (by scoffers) with some unequal dealing towards a great number of good English words. For as it is written of a certain great philosopher, that he should say that those logs were happy that were made images to be worshipped; for their fellows, as good as they, lay for blocks behind the fire: so if we should say, as it were, unto certain words, ‘Stand up higher, have a place in the Bible always’, and to others of like quality, ‘Get ye hence, be banished for ever’, we might be taxed peradventure with St James’s words, namely, ‘To be partial in ourselves and judges of evil thoughts’. Add hereunto that niceness in words6 was always counted the next step to trifling,7 and so was to be curious about names too: also that we cannot follow a better pattern for elocution than God himself; therefore he using divers words in his holy writ, and indifferently for one thing in nature,8 we, if we will not be superstitious, may use the same liberty in our English versions out of Hebrew and Greek, for that copy or store that he hath given us. Lastly, we have on the one side avoided the scrupulosity of the Puritans, who leave the old ecclesiastical words, and betake them to others, as when they put ‘washing’ for ‘baptism’, and ‘Congregation’ in stead of ‘Church’: as also on the other side we have shunned the obscurity of the Papists, in their ‘azymes’, ‘tunic’, ‘rational’, ‘holocausts’, ‘praepuce’, ‘pasche’, and a number of such like whereof their late translation is full, and that of purpose to darken the sense, that since they must needs translate the Bible, yet by the language thereof it may be kept from being understood. But we desire that the Scripture may speak like itself, as in the language of Canaan, that it may be understood even of the very vulgar.

___________

3 Πολύσημα.

4 ‘A bed’. Nicephorus Callistus, Ecclesiastica Historia, 8:42 (PG 146:165).

5 St Jerome, Commentarii in Ionam, 4:6 (CC 76:414; PL 25:1147). See St Augustine, Epistulae, 71:3:5 (PL 33:242).

6 Λεπτολογία.

7 Ἀδολεσχία.

8 Τὸ σπουδάζειν ἐπὶ ὀνόμασι. See Eusebius, Preparation for the Gospel, 12:8:4 (PG 21:968), alluding to Plato, Statesman (Politicus, 261e).

– David Norton, Ed., The New Cambridge Paragraph Bible with the Apocrypha: King James Version, Revised edition, xxxiv–xxxv. Hereafter NCPB.

Under the fifteenth and final heading of their preface, Reasons inducing us not to stand curiously upon an identity of phrasing, the translators explain their second and final specific note about procedure (their first note about procedure related to the use of marginal notes, as we explain here). Two issues are taken up. The first issue here is liberty with words, the bulk of the section. It addresses three aspects of this liberty; lack of consistency in how they render certain words and phrases, then, the partiality they showed to some words, and finally, the diversity of words they did choose. The second issue they take up is their choice to reject both Catholic obscurantism and sectarian (Puritan) innovation.

The First Issue – Shunning Consistency Of Rendering, Or Making, “Verbal And Unnecessary Changings”

To the first issue they note,

Another thing we think good to admonish thee of, gentle reader, that we have not tied ourselves to a uniformity of phrasing, or to an identity of words, as some peradventure would wish that we had done, because they observe that some learned men somewhere have been as exact as they could that way.

– NCPB, xxxiv.

Hugh Broughton And The Theological Case For Literal Translation

They may well have in mind here Hugh Broughton, generally regarded as perhaps the greatest Hebrew scholar of that age. He didn’t end up working on the KJV, (contrary to claims that the KJV companies contained all of the best scholars of the age). He felt that belief in the inspiration and infallibility of Scripture demanded the most literal translation possible. If a Hebrew word or phrase had one meaning, then it should be translated into English only one way, and consistently so throughout the translation. A phrase translated one way in one place should be translated the same way if it occurs in another, unless the intent is different. His concern was deep accuracy to the original text. He set out eight principles of translation in 1597 that he suggested translators should follow, for;

The holy text must be honored, as sound, holy, pure: heed must be taken that the translator neither flow with lies nor have one at all: prophecies spoken in doubtful terms, for sad present occasions, must be cleared by said study and staid safety of ancient warrant: terms of equivocation witty in the speaker for familiar and easy matters, must be looked unto, that a translator draw them not unto foolish & ridiculous senses: Constant memory to translate the same often repeated in the same sort is most needfull.

– Hugh Broughton, An Epistle to the Learned Nobilitie of England...

He was convinced that God had supernaturally preserved every single letter of the Hebrew text in the Masoretic Text (he would later be upset with the KJV translators, presumably partly for how often they emended the Hebrew text with the LXX and Latin Vulgate). The original text must not be trifled with by translators. God cared not only about the sense, and not only about the sentence, but about every single word. God’s text was perfect; “These being matters of Elegancy more than bare necessity, shew that no lesse watchfulness was over the words of sentences. Which thing should move us to hold the text uncorrupt.”

Against those who might maintain (like the KJV translators) that the text had been corrupted and needed restored via textual criticism, Broughton seemed convinced that to say this was to concede to Catholic arguments, “then would the papists earnestly triumph, that we Protestants confess the text to be corrupted: That will I never do, while breath standeth in my breast.” In fact, while the KJV translators would lean most heavily on the 1598 Greek text of Beza, Broughton was convinced Beza and his numerous text-critical notes (which largely shaped the KJV) were an attack on the preservation of the NT text. And to allow the kind of textual criticism that Beza employed was to give in to the Catholics, and to give up the faith altogether;

If the text of the New Testament be corrupt, it can not be from God. But Th. B. [Theodore Beza] spent sixty years to prove that it is most corrupt, & hath full many long speeches to prove that, and triumphet what infinite variety of copies he hath seen, and him you hold your chief…Therefore by this doctrine your New Testament should not be from God: for God would keep that which he gave, as our Hebrew to every yod.”

– Hugh Broughton, A Require of Agreement…1611.

He drew a theological connection between the inspiration and preservation of Scripture, and a literal translation of it. Because of his high views of the perfection of every sentence, word, and even letter of the text, he was passionate that the translator must be exactly literal with the text. He must be consistent in how he renders each word. In his fifth rule for translators, he noted; “The next point that I am to handle, is most pleasant: and the missing in it argueth not want of learning, but of leisure. It containeth constant memory to translate the same often repeated in the same sort: and the differing repetitions likewise with their differences.” Translators who weren’t always literal and consistent in translating the same phrases or words the same way were, for Broughton, traitors to the pure text of Scripture.

The Disagreement Of The KJV Translators

Yet the KJV translators explicitly disagreed. They do note that when their conscience compelled them they would be consistent; “Truly, that we might not vary from the sense of that which we had translated before, if the word signified the same thing in both places (for there be some words that be not of the same sense everywhere), we were especially careful, and made a conscience, according to our duty” (NCPB, xxxiv.). But they simply didn’t feel the need for the kind of literalism with words that Broughton and others were advocating. They felt more liberty than that, and, ” asserted their freedom to use the target language, English, creatively, refusing to be ‘tied’ to any ‘uniformity of phrasing,’” as Wilcox notes.

They provided a few illustrative examples. But they chose as illustrations some of the mildest examples of a class which primarily includes far more extreme instances. Thus, while the heading refers to “phrasing” being varied, and while their practice shows entire sentences rendered differently, their provided examples all relate only to a single wordbeing translated with two different single words. Their actual liberties were much more drastic than this statement might lead us to believe.

“The Translators To The Reader” serves as the Preface to the KJB.

To note one line of evidence, F.H.A. Scrivener counted 8,422 marginal notes in the original 1611 KJV, of which 4,223 provide more literal translations (part of their regular acknowledgement that the text was not as literal as it could be), and 2,738 provide “alternate” translations to those provided in the text. And they are far from noting every such case in the margin. These humble whispers (explained in the prior section of the preface that we don’t cover here, listed out in the full exposition of the preface linked to above) assure us that the translators entertained no notion that the renderings of the KJV were the only accurate ones, or the most exact, or most literal, that could be made.

But that we should express the same notion in the same particular word, as for example, if we translate the Hebrew or Greek word once by ‘purpose’, never to call it ‘intent’; if one where ‘journeying’, never ‘travelling’; if one where ‘think’, never ‘suppose’; if one where ‘pain’, never ‘ache’; if one where ‘joy’, never ‘gladness’, etc.; thus to mince the matter, we thought to savour more of curiosity than wisdom, and that rather it would breed scorn in the atheist than bring profit to the godly reader.

– NCPB, xxxiv.

They believe that to “express the same notion in the same particular word” every time that notion occurs in Scripture would be to “mince the matter.” It would be a scrupulous over-attention to details. In their opinion, this would be to “savor more of curiosity than wisdom,” and such an approach they wholly reject. (The word “curiosity” is an archaic way to refer to scrupulousness.) They are speaking about “pedantry,” or “literalism.” In fact, they feel that to seek such literalism would cause the KJV to be scorned by atheists, and render less help to the Christian reader. They are not tied to uniform phrasing, but rather express the freedom and liberty which they felt with words. They are concerned to communicate the content and ideas of Scripture, not its exact words.

They draw an analogy from Paul’s words about Christian liberty in Romans 14. He argued that the Christian had liberty in issues like Jewish dietary laws. He could keep them or not. Christians shouldn’t fight about them, because we have liberty to do as we please, following only our own consciences. Paul advocated liberty, “for the kingdom of God is not meat and drink; but righteousness, and peace, and joy in the Holy Ghost.” The translators felt a like liberty to render words however they saw fit. No one should argue about precise verbal forms. That’s not the stuff the Kingdom is made of. They defend, “this apparently bold method—potentially tampering with the Word of God—in a series of rhetorical questions” (Wilcox), and so they ask;

For is the kingdom of God become words or syllables? why should we be in bondage to them if we may be free? use one precisely when we may use another no less fit as commodiously?

– NCPB, xxxiv.

Their point of course, as Wilcox explains, is that, “those preparing the new biblical version should not be bound or limited in ways that would reduce the power of the divine word; their text can express spiritual matters and achieve its impact through their exercise of discriminating linguistic taste.” They have and intend to use a greater freedom with language than many would consider appropriate when dealing with the word of God, should precision be the highest goal. But for them, “Mere precision of language is set against the greater value of ‘fit’ words and the choice of ‘commodious’ English vocabulary—that is, those words most likely to profit the reader’s soul.”

Historic Examples When Liberty With Words Caused A Stir

They then provide two examples from church history where liberty with words in translation had caused quite a stir. Their point is to show that the objections against them for not being scrupulously literal are nothing new, and are to be expected. They are well aware that people get somewhat emotionally attached to the Scriptures in a certain verbal form and, as they mentioned earlier, “cannot abide to hear of altering.” They know they will be accused of “meddling with men’s religion” by all the liberties they take with the original text. In the two examples they provide, minor and insignificant verbal changes had caused a stir. The stir about their even greater liberty with words is thus to be expected.

First comes an example from a Bishop Triphyllius in the late IV century, who had substituted a different word in an exposition of Mark 2:9. The phrase “take up thy bed and walk,” using the word krabbaton for bed, had apparently been presented in an exposition using instead the word skimpous for bed. They have a slightly different nuance, but the same basic meaning. However, according to the story as recounted in Nicephorus, St. Spyridon had harshly rebuked the Bishop for not being exact with the words of Scripture. Or, in the words of the translators, “A godly Father in the Primitive time showed himself greatly moved, that one of newfangledness called krabbaton, skimpous, though the difference be little or none…” They regard the rebuke of St. Spyridon as unnecessary.

Second comes a more well known example from the Latin Vulgate of Jerome. The translators refer in the margin both to a text in Jerome’s commentary on Jonah that mentions the incident and to Augustine’s epistle to Jerome which recounts it. The Old Latin texts, translated from the Greek LXX, had apparently used the word “cucurbita” or “gourd” for the description of the plant in the text in Jonah 4:6. But when Jerome produced his revision of the Latin, going back to the Hebrew, he had determined that the Hebrew word more properly was hedera or “ivy.” Augustine had described the situation in his letter to Jerome;

St. Augustine, by Sandro Botticelli.

“A certain bishop, one of our brethren, having introduced in the church over which he presides the reading of your version, came upon a word in the book of the prophet Jonah, of which you have given a very different rendering from that which had been of old familiar to the senses and memory of all the worshippers, and had been chanted for so many generations in the church. Thereupon arose such a tumult in the congregation, especially among the Greeks, correcting what had been read, and denouncing the translation as false, that the bishop was compelled to ask the testimony of the Jewish residents (it was in the town of Oea). These, whether from ignorance or from spite, answered that the words in the Hebrew manuscripts were correctly rendered in the Greek version, and in the Latin one taken from it. What further need I say? The man was compelled to correct your version in that passage as if it had been falsely translated, as he desired not to be left without a congregation,—a calamity which he narrowly escaped.”

– Augustine, Epistle 71.3.5

Or, in the translators’ words, “…and another reporteth, that he was much abused for turning Cucurbita (to which reading the people had been used) into Hedera.” They conclude that their own “verbal and unnecessary changings” will of course meet similar opposition, “Now if this happen in better times, and upon so small occasions, we might justly fear hard censure, if generally we should make verbal and unnecessary changings.” This is what they claimed to have done. They have changed the words of the text in places where change was not needed. And they are aware that some will oppose this. David Norton, expert historian of early English Bibles, explains that, “In this the translators were following the example of their predecessors and also reflecting a certain looseness in the spirit of the age. Variety of translation is at one with the tendency to inconsistent phrasing of quotations from the Bible evident in the preface itself and in a number of seventeenth-century writers.” But as he notes, “a large number of scholars came to think, with Broughton, that inconsistency was a mistake. The preface to the RV NT calls it ‘one of the blemishes’ in the KJB, and the RV followed the opposite policy.” He goes on to provide an illuminating example;

An example will help to demonstrate this. One of the KJB’s most famous lines, ‘consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they toil not, neither do they spin’ (Matt. 6:28), is also rendered, ‘consider the lilies how they grow: they toil not, they spin not’ (Luke 12:27). The second version is little known and inferior as English. As translations, they render different Greek verbs with the same English word, ‘consider’. The first variation (‘lilies of the field’, ‘lilies’) exactly reflects a difference in the Greek: the resonant phrase exists because of literal translation. The last part of the sentence is identical in the Greek of both gospels… but the KJB in one instance produces the memorable cadence of ‘they toil not, neither do they spin’ and in the other more accurately reflects the structure of the Greek in the staccato pair of parallel phrases, ‘they toil not, they spin not’. Thus three aspects of the KJB translators’ work can be seen in this one example: failure to distinguish between different words in the original, literal translation happily producing a phrase of memorable quality, and varying translations in one case producing another such phrase. There is no way of knowing if the last variations were produced for literary reasons, or even, if they were, which version the translators actually considered the better: they could have argued for the parallelism of Luke’s version.

The fact that the translators deliberately adopted this policy of inconsistency (even if only because of precedent) is the only evidence that shows a sense of responsibility towards the English language. However, the passage from the preface does not show genuinely literary motives, even if it lays open the way for choice of vocabulary on literary grounds. The concern is still with precision. ‘Fit’, as has been shown, does not carry aesthetic connotations, and ‘commodiously’ is used in the sense of usefully or beneficially for conveying sense. A similar point is made by Ward Allen about the final phrase quoted: ‘by niceness Dr Smith means the domination of thought by words rather than the domination of words by thought, or exactness’ (Translating for King James, p. 12).

– Norton, David, A History Of The English Bible As Literature, pp. 68-69.

Some Examples Of Liberty With Words

It may be instructive to examine a few examples from their work of what they mean by the “verbal and unnecessary changings” which they have made (I am indebted to Bishop Ellicott for many of these examples);

OT Passages Rendered Inconsistently In The NT

Many examples could be provided here. Gen. 15:6 is quoted (probably from the LXX) three different times in the NT (Rom. 4:3; Gal. 3:6; James 2:23), always with identical wording (only the word order differs). But each time, the translators have slightly varied the way they translated it;

– “Abraham believed God, and it was imputed unto him for righteousness.” (Jam 2:23)

– “Abraham believed God, and it was accounted to him for righteousness.” (Gal 3:6)

– “Abraham believed God, and it was counted unto him for righteousness.” (Rom 4:3)

Deut. 32:35 is quoted twice in the NT (Rom. 12:19; Heb. 10:30), probably from the LXX, (the form is different still from the Hebrew MT, and the KJV translation of it), both times in the same words in the Greek text, but rendered differently both times in KJV;

– “For we know him that hath said, Vengeance belongeth unto me, I will recompense, saith the Lord.” (Heb 10:30, KJV)

– “For it is written, Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord.” (Rom 12:19, KJV)

Psalm 95:11 is quoted (from the LXX) by the author of Hebrews twice, and the text is verbally identical both times (3:11 and 4:3). But the translators made the choice to render the same quotation in two different ways.

– “So I sware in my wrath, They shall not enter into my rest.” (Heb 3:11, KJV)

– “As I have sworn in my wrath, if they shall enter into my rest…” (Heb 4:3, KJV)

The English reader who does not understand the liberty they have taken with words might think these quotation to have occurred in two different forms. Yet this is not the case. When KJVO folks challenge me to prove “even one error of translation in the KJV” I usually point them to these two passages. We have here exactly the same Greek text, yet KJV translators translated the exact same text in two totally different ways in two different passages. Nor could one claim that different authors are interpreting the text in two different ways, for the author and context is identical. Since the KJV renders both passages differently, if literal and exact translation is the standard of measure, then they are undeniably mistaken in at least one of these translations.

Intentionally Repetitious Language Rendered Variously

Numerous such passages exists. In Rom. 4, the same Greek lemma for “accounting” occurs 11 times, meaning the same thing in each case. Paul intends the repetition to show that the same “counting” that was given to Abraham is given to all who come to Christ by faith. But the translators chose three different words variously to translate it with here; sometimes as “counted,” other times, “reckoned,” others, “imputed.” Paul’s point is to build the connections between his use of the word – consistency is important to his meaning. Yet the English reader who was unaware of their liberties might think there to be three different Greek words here, and thus miss the connections Paul is making.

In Rom. 7:7-8, the verb for “covet” and its noun form is repeated by Paul to make a point. Yet it is translated variously as “lust,” “covet,” and “concupiscence” by the translators, ignoring the fact that it has the same meaning in each place. They have created variety where Paul intended to create repetition. The reader who was unaware of their liberties with words, or who took the words of their translation too seriously, might easily miss Paul here.

In I Cor. 3:17, Paul uses a play on words when he writes, “If any man destroy the temple of God, him shall God destroy,” using the same word twice. He even arranges the words next to each other in the sentence to highlight his wordplay. But the translators translated the first as “defile” and the second as “destroy.” Inconsistency is created where Paul intended consistency to make a point.

Throughout II Cor. 1 the pair of words for “comfort” and “affliction” are intentionally repeated and paired against each other numerous times by Paul. Yet the translators variously render these same two words as, “comfort,” “affliction,” “tribulation,” and “consolation” in the passage, creating variety where there was none in the original, and losing Paul’s rhetorical impact.

Mark used the adverb “immediately” some 42 times throughout his gospel, connecting the various narratives with a consistently vivid pace. But what Mark in most cases intends as a regular literary device, the KJV’s liberty with words has obliterated. It varies the translation of Mark’s adverb by variously translating with;

– “immediately” (commonly)

– “straightway” (Mk. 1:10, 18, 20-21; 2:2; 3:6; 5:29, 42; 6:25, 45, 54; 7:35; 8:10; 9:15, 20, 24; 11:3; 14:45; 15:1)

– “forthwith” (Mk. 1:29, 43; 5:13)

– “anon” (Mk. 1:30)

– “as soon as” (Mk. 1:42; 5:36; 11:2; 14:45)

The English reader unaware of the liberty with words that the translators took could easily miss Mark’s intentional repetition of the same word for literary effect. They have created a variety that the original text simply did not have.

Identical Gospel Parallels Rendered Inconsistently

One might also note parallel passages that occur in the gospels, where the wording between the Evangelists is identical in Greek, but where the KJV has translated the texts differently. These might give the mistaken impression to the English reader of greater variance between the gospels than actually exists in the Greek text being translated. A few examples (from hundreds) make the point;

– Mt. 4:6/Luke 4:10 – concerning/over

– Mark 1:17/ Matt. 4:19 – follow/ come ye after

– Matt. 10:14/Luke 9:5 – the dust/the very dust

– Matt. 10:22/ Mark 13:13 – he that endureth to the end shall be saved/he that shall endure the same shall be saved

– Matt. 17:19/Mark 9:28 – apart/privately

Various Other Inconsistencies

Consider the one Hebrew word sometimes translated, “face.” Strong’s lexicon lists only two basic definitions for the word with a variety of applications of those definitions;

(1) “The face (as the part that turns); used in a great variety of applications (literally and figuratively)”

(2) “also (with prepositional prefix) as a preposition (before, etc.)”

Modern lexicons like HALOT, with slightly more scholarly nuance, list some 15 basic meanings, with slight distinction among each. Yet this one word was rendered some 83 different ways by the KJV translators. Surely, in so many instances of this word in the Hebrew Bible, it has several different meanings, and good translation respects this. But there are clearly not eighty-three distinctly different meanings of the word. The English reader who wasn’t aware of the translator’s liberty with words might easily think some eighty different words to occur in the original text. But he would be mistaken. This is rather another instance of their taking liberty with words. We could raise a similar point with the example of the Hebrew word for “hand.”

Or, from another direction, there are some 45 distinctly different Hebrew and Aramaic words, (and around 12 different Greek words) that are simply rendered with the single English word “destroy” in the KJV (see a full list here). This failure to be more precise obliterates the various nuances and distinctions that the original language texts employed between these words. Yet in other passages, the translators have used some 80 different English expressions to render these same Hebrew and Aramaic roots, so it is not as if they didn’t have a store of English words to present the distinctions of the original with. They were creating what they called, “verbal and unnecessary changings.” The English reader who didn’t understand the liberty they took with words might think every occurrence of “destroy” in its different forms to have meant the same thing to the original readers. But this would not be the case.

The Greek word elpis occurs fifty-four times in the Greek text of the KJV NT. It is rendered, “hope” fifty-three times. Yet in Heb. 10:23, it is inexplicably (mis)translated, “faith” (against all earlier English translations, and against all lexical sense). This is so absurdly inconsistent that it is usually concluded to be simply a printing mistake never corrected in the KJV (except in Scrivener’s CPB edition). But Norton in the NCPB retains the reading of the 1611 edition (“faith”) noting;

This could be a printer’s error because of ‘faithfull’ later in the verse, but the 1611 reading has been accepted by most editors.

Whether an accidental error that remains uncorrected in the KJV, or another example of their “liberty,” it nonetheless reflects their inexactness, which changes the meaning of the author’s text.

Gerald Hammond demonstrates at length that the KJV was far more consistent in such linguistic issues than the English translations that came before it (though less consistent than those that came after it). In fact he ultimately concludes that the KJV’s consistency of style is “why it kept so powerful a hold over English minds for the next three hundred and fifty years” (Gerald Hammond, The Making Of The English Bible, pg. 233). But even in a work positing such a bold thesis, he qualifies that, “We should not assume that the translators aimed for complete consistency” (pg. 199), noting that, “The Authorized Version makes no special attempt to maintain a complete consistency of rendering where one English word is, wherever contextually possible, used to translate one particular Hebrew word.” (pg. 201-202).

In each of these cases, and thousands more that we could list, it becomes clear that the KJV translators did not feel tied to a particular verbal form for their translation. They did not seek to be verbally exact or verbally consistent in their translation. They explained this from the very start so that no one would take the words of their translation too seriously. As Alister McGrath explains;

The translators also avoided what—at least, to them—seemed a wooden and dogmatic approach to translation, which dictated that precisely the same English words should regularly be used to translate Greek or Hebrew words. The preface sets out clearly the view that the translators saw themselves as free to use a variety of English terms…

This principle suggests that the translators saw variety as a means of enhancing the beauty of the text, by avoiding crude verbal repetitions. Yet it must be pointed out that this principle led to some quite puzzling consequences. The translation of Romans 5:2–11 reveals this concern to ensure variety. According to the King James Bible, Paul and his colleagues “rejoice in hope of the glory of God… we glory in tribulations… we also joy in God.” The same Greek verb—which would normally be translated as “rejoice”—is, in fact, being translated using different words (here italicized) in each of the three cases. There can be no doubt that this flexibility allowed the translators to achieve a judicious verbal balance that enhanced the attractiveness of the resulting work. Yet inevitably a price was paid for this in terms of the accuracy that some had hoped for.

– McGrath, Alister. In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, a Language, and a Culture, pp. 193-194.

Election And Reprobation Of Language – “Unequal Dealings” With Words

Having explained their intention to make “verbal and unnecessary changings” they then take up in the preface the second issue in their liberty with words; the reason they often chose one English word or phrase but rejected another. Using an interesting analogy from a philosopher’s comment, they build a vivid picture. Imagining a forest of trees, the philosopher reflects on the fact that some of these trees will be shaped into idols by pagans to worship. But ironically, some of these very same trees will be turned into firewood to be burned. In a somewhat arbitrary choice, some trees have a destiny as worthless as firewood, and other of the exact same trees have a destiny as an object of worship. The translators draw an analogy to their sometimes arbitrary choice of one word over another. Perhaps from the doctrine of election, the translators suggest that they have been quite partial in “electing” some words to become part of biblical language, and “damning others” to remain only part of the common but not biblical vocabulary. They conclude by quoting James and asserting themselves as judges of words;

We might also be charged (by scoffers) with some unequal dealing towards a great number of good English words. For as it is written of a certain great philosopher, that he should say that those logs were happy that were made images to be worshipped; for their fellows, as good as they, lay for blocks behind the fire: so if we should say, as it were, unto certain words, ‘Stand up higher, have a place in the Bible always’, and to others of like quality, ‘Get ye hence, be banished for ever’, we might be taxed peradventure with St James’s words, namely, ‘To be partial in ourselves and judges of evil thoughts’.

– NCPB, xxxiv.

Freedom In Wording – Rejecting “Niceness In Words”

In the third aspect of the liberty they have taken with words, they point out the abundant store of linguistic vocabulary that has been furnished for them by God in English, and even the pattern He has set by varying in Scripture the language He uses to describe things, with an apparent indifference (they think) to the exact wording. In rejecting a focus on words that they consider, “trifling,” they believe they are actually following God’s example;

Add hereunto that niceness in words was always counted the next step to trifling, and so was to be curious about names too: also that we cannot follow a better pattern for elocution than God himself; therefore he using divers words in his holy writ, and indifferently for one thing in nature, we, if we will not be superstitious, may use the same liberty in our English versions out of Hebrew and Greek, for that copy or store that he hath given us.

– NCPB, xxxiv.

Thus, in this section dealing with their desire to “use the same liberty in our English versions” and to not tie themselves to a “uniformity of phrasing,” they have made it clear that they feel free to make “verbal and unnecessary changings.” They are “admonishing” the reader to be careful not to focus too much on the precise words of their translation; they certainly did not. They are more concerned with the message than the exact verbal form. They are not bound by exactness of words, and they don’t want the reader to be either.

For is the kingdom of God become words or syllables? why should we be in bondage to them if we may be free, use one precisely when we may use another no less fit, as commodiously?

– KJV Translators

The Second Issue – Creating A Vulgar Version, Or, Speaking in “The Language Of Canaan”

After explaining in three parts their liberty with words, they then take up briefly the second issue concerning their handling of words, which is the balance they sought between traditionalism and obscurantism. They sought to stand between tradition and innovation. For the most part, their translation will retain traditional and familiar language, eschewing any innovation, and trodding the already the well-worn verbal paths of prior English versions. But there are other ways in which they will blaze new trails with their work.

This Bible was new and at the same time not new, presented as the sacred word for the future and yet full of deliberate archaisms and links with previous versions. The KJB’s compromise between the given past and the ordained future may be seen in the detail of the revisers’ choices: the voices of Tyndale and Coverdale, the tones of the Roman Catholic Douai Bible, and phrases of the Protestant Geneva Bible are all to be heard within the verbal echo-chamber of the KJB, yet it has its own distinctive cadence and blend of vocabulary, particularly in areas of Jacobean theological controversy such as priesthood and the church. Ironically yet typically, the engraved title-page of the New Testament in the KJB is actually borrowed from the last edition of the old Bishops’ Bible (1602), asserting visually as well as verbally the new Bible’s acknowledged line of inheritance.

– Wilcox, The KJB In Its Cultural Moment

KJV NT title page, repurposing a woodcut from the 1602 Bishops Bible.

We won’t examine this section of the preface in detail here, though it is worth noting. They rightly understood that these are two sides of the same issue, and that wise translation should seek a medium between the two. Translation should be into the vulgar tongue, or the language of the common man. The goal should be to make the Bible understood. But a translator can find a ditch on either side, becoming either too novel or too obscure. All translation seeks to lessen the distance between the modern reader and the original one. Yet in our attempt to speak a contemporary word, we dare not speak a faddish one. They shun both what they consider sectarian (that is, Puritan) novelty, and Catholic obscurantism. They would rather avoid both extremes, and speak instead the language of the common man.

Lastly, we have on the one side avoided the scrupulosity of the Puritans, who leave the old ecclesiastical words, and betake them to others, as when they put ‘washing’ for ‘baptism’, and ‘Congregation’ in stead of ‘Church’: as also on the other side we have shunned the obscurity of the Papists, in their ‘azymes’, ‘tunic’, ‘rational’, ‘holocausts’, ‘praepuce’, ‘pasche’, and a number of such like whereof their late translation is full, and that of purpose to darken the sense, that since they must needs translate the Bible, yet by the language thereof it may be kept from being understood. But we desire that the Scripture may speak like itself, as in the language of Canaan, that it may be understood even of the very vulgar.

– NCPB, pg. xxxiv–xxxv.

As Mark Ward has noted at length in “Authorized,” (and Noah Webster in his own work cited at that link), their translation today, however valuable, can no longer accomplish this, their ultimate stated goal in translation. Indeed, as I note in my review at that link, they probably missed that mark the very first and only time they drew their bow, however carefully they may have aimed for it.

Advocates for Literal Translation, Modern And Ancient

Contrary to what is sometimes alleged, the KJV does not represent a perfectly “literal” translation of the text with unflinching exactness. And this is not some accident, mistake, or failure on the part of the translators. Rather, the inconsistency of rendering was a stated intention of the KJV translators who took great liberty with words. Anyone who wants to insists today that every single word of the KJV represents exactly the way it “should” be rendered in English, or wants to argue about the exact phrasing or wording of the KJV will find the greatest objectors to be the Translators themselves. They would no doubt be saddened by those who have made the kingdom of God into words and syllables, and who have taken their words so seriously.

Contrary to what is sometimes alleged, the KJV does not represent a perfectly ‘literal’ translation of the text with unflinching exactness.

But if someone does oppose translators taking this kind of liberty with the text in translation, it is informative to note that some translations today do not take such license. The ESV, for example, in its passion for what its translation committee refers to as “essentially literal” translation, has rejected the precedent of liberty set by the KJV here. In their preface they explain;

The ESV is an “essentially literal” translation that seeks as far as possible to reproduce the precise wording of the original text and the personal style of each Bible writer….Every translation is at many points a trade-off between literal precision and readability, between “formal equivalence” in expression and “functional equivalence” in communication, and the ESV is no exception. Within this framework we have sought to be “as literal as possible” while maintaining clarity of expression and literary excellence. Therefore, to the extent that plain English permits and the meaning in each case allows, we have sought to use the same English word for important recurring words in the original; and, as far as grammar and syntax allow, we have rendered Old Testament passages cited in the New in ways that show their correspondence. Thus in each of these areas, as well as throughout the Bible as a whole, we have sought to capture all the echoes and overtones of meaning that are so abundantly present in the original texts.

Leland Ryken notes that this is one of the clearest differences between the KJV and the ESV. To be sure, the register of the English style, and the text-critical differences between the Greek text of the KJV and the Greek text of the ESV create the largest amount of what little difference there is between the two versions. But if one sets the text-critical advances behind the ESV to the side, it is the consistency of the ESV that appears as the starkest difference between the KJV and ESV;

The most obvious difference between the KJV and the ESV centers on the issue known today as concordance. Concordance in this case means using the same English word for a given Hebrew or Greek word every time (or nearly every time) it occurs in the Bible. Concordance was a high priority for the ESV translators. This was inevitable because of the commitment to verbal equivalence. The King James translators did their work at a moment in history when the English language was expanding at an unprecedented rate and when excitement about the burgeoning possibilities of language ran high. It was a time of lexical and linguistic exhilaration. This is the context for the famous statement about synonyms that appears in the preface to the KJV: [He then cites the passage we quoted above.] The decision to multiply synonyms reflects Renaissance exuberance over words and is not governed by fidelity to the biblical text. It is my impression that the decision of the King James translators to provide variety rather than consonance for a given Hebrew or English word makes the KJV a less literal translation.

The ESV parts company with the KJV on this issue. The goal of the translators was to maintain as much concordance as possible (only occasionally departing from it). The preface states, ‘We have sought to use the same English word for important recurring words in the original.’

There is a complex additional dimension to concordance, namely, making New Testament quotations from the Old Testament as parallel as the original text allows. The ESV translators strove for concordance on this matter also. In the words of the preface, “As far as grammar and syntax allow, we have rendered Old Testament passages cited in the New in ways that show their correspondence.

– Ryken, Leland. The ESV and the English Bible Legacy, pp. 103-104.

Whether Ryken and his translation philosophy is the best one is not the point here. That is a hotly contested issue in translation today. The point here is that if one believes that the most literal translation is automatically the besttranslation, then the ESV seems to have an upper hand over the KJV. In fact, every single one of the examples of inconsistency I’ve listed above, (and thousands of others I’ve not mentioned) is corrected in the ESV. Claims that the KJV is the “most literal” or “the most exact” are simply not accurate. In fact, this is a moniker that should go to an interlinear text rather than a translation to begin with. Beyond that, it should certainly go to woodenly literal translations like the Young’s Literal Translation of the TR, or at best works like the NASB, before it would go to the KJV. Broughton would be proud.

Personally, I am of the opinion that while literal translation has a distinctly important place in English Bible translation, we lose the value of a different kind of accuracy when we prioritize a literal approach over a more functional approach. We should value both. As NT Wright has well noted,

There are at least two sorts of accuracy. The first sort, which a good Lexicon will assist, is the technical accuracy of making sure that every possible nuance of every word, phrase, sentence and paragraph has been rendered into the new language. But there is a second sort of accuracy, perhaps deeper than this: the accuracy of flavour and feel. It is possible, in translation as in life, to gain the whole world and lose your own soul – to render everything with a wooden, clunky, lifeless ‘accuracy’ from which the one thing that really matters has somehow escaped, producing a gilded cage from which the precious bird has flown. Such translations – the remarkable Revised Version of the 1880s might be one such [he later lists an example from the KJV as another] – are of considerable use to the student who wants to get close to the original words. They are of far less use to the ordinary Bible reader who wants to be grasped by the actual message of the text.

– NT Wright, The Monarchs and the Message.

This is one reason why I don’t think anyone should only use the KJV, or only use any one translation. The wisest Bible readers read from different translations that come from opposing ends of the spectrum. But for those who prioritize literal translation, hopefully this note has shown that the KJV does not automatically hold the position of being most faithful to a literal translation philosophy.

Of course, modern scholars like Ryken are not the only ones who oppose the carefree approach of the KJV. As we noted above, Hugh Broughton had been advocating for a decade before the birth of the KJV that a translator must be literal and consistent. He wrote a letter to the translators during their work to provide them more advice. Norton summarizes;

It was perhaps his last attempt to influence the KJB, if only by opening the way for post-publication criticism… ‘We should’, he continues, ‘by common consent, for near tongues, express this variety, that the holy eloquence should not be transformed into barbarousness. By right dealing herein, great light and delight would be increased. The Hebrew would be in honour among all men when the inimitable style should be known how it expressed Adam’s wit’ (Works, III: 702). At the back of this lies an equation between literal translation and eloquence in translation: the translation would be eloquent not as English but as Hebrew and Greek in English….

Much of Broughton’s work was ignored. But however little the KJB translators responded to its detail, it contributed significantly to the intellectual atmosphere of the time by encouraging a reverence for the eloquence of the original without arguing for an equivalent eloquence in English, but above all by demanding the whole truth and arguing that it could only be revealed through the closest attention to the words and syllables of the perfect originals.

– Norton, David. A History, Page 60.

But the KJV translators shared neither Broughton’s view of the perfection of the original text, nor his conviction that such a view of the Bible required a meticulous consistency in rendering. And so they pressed on in the employment of their more carefree principles.

How did he feel about the final product? He read the the new translation, and immediately sent the King his conclusions. He raised ten points of contention against it; it weakened the doctrine of the deity of Jesus, failed to respect the purity of the original text, mistranslated portions, created contradictions in the text, etc. And so on he went, ironically, briefly employing many of the same objections raised against modern versions by some advocates of the KJV. (They would find an ally in his arguments, if not for the fact that the conclusion of their use of the arguments was the very object of his attack by them.) They had essentially broken every rule of translation he had been urging over the previous decades. They had failed—intentionally—to be fully exact with the original language text, which he felt was the true mark of faithful translation. He shared his final evaluation of the KJV in the strongest of words;

The late Bible, Right Worshipful, was sent me to censure [examine]: which bred in me a sadness that will grieve me while I breathe. It is so ill done. Tell his Majesty that I had rather be rent in pieces with wild horses, then any such translation by my consent should be urged upon poor Churches….Bancroft raved. I gave the Anathema. Christ Judged his own cause. The New edition crosseth me, I require it be burnt.

– Hugh Broughton, A Censure of the Late Translation, 1611.

Fortunately, not all copies of the KJV were burned when it appeared. Instead, it eventually became the standard English Bible, a place it held for some 200 years. As I have noted elsewhere, this was due less to its merit as a translation and more to the political and economical maneuvering of those who most profited from it. But nonetheless, it came to mark the English world, and had an influence on the English language second only to Shakespeare. It remains to this day a helpful translation that is still in use and still conveying the Word of God with beauty to many an English reader. In fact, it is quite likely the most elegant English translation that will ever be produced. I often suggest that every single English reader should own and use a copy of the King James Bible (though I don’t think anyone should only use a KJV).

But one can’t help but wonder – how much of the “strangeness” that makes the voice of the King linger in our ear, and in our hearts, is due to those “verbal and unnecessary changings” which the translators have made with such liberty? How much of their (arguably unintentionally) elegant and beautiful prose is a result of their inexactness of translation? Norton noted one example above (Matt. 6:28) where their less literal translation rendered the memorable and poetic line that has stuck with us far more than its more literal brother. How many more such examples could be provided?

Has their controversial linguistic liberty become the genius of their literary legacy?

Comments