King James Bible History

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut condimentum scelerisque dapibus. Proin eget diam euismod.

Love’s Labor Lost – Charity Revived In The A.V.

In our last post, we traced the debates between William Tyndale and Thomas More about the word “charity.” When it came to the English Bible, More was convinced we should follow the lead of the Latin Vulgate in creating a distinction between “love” in most passages where the Greek agape occurs, verses “charity” in some of those passages. Tyndale was adamantly opposed, claiming that the English “charity” has a different meaning. More charged Tyndale with trying to slip in Luther’s doctrine of justification by faith alone. Tyndale didn’t disagree, but didn’t see himself as slipping in anything – he was adamant that the English Bible should teach justification by faith alone, because that was, he was convinced, what Paul himself taught in the original Greek. See the last post for all those details.

Love Lost – The AV Rendering

But having looked at Tyndale’s valiant fight to banish charity from the English Bible, convinced as he was that it was no English word that could capture the sense of the Greek agape, we now face the question – what happened to Tyndale’s love in the Authorized Version? Studies have shown that the KJV NT is 83.7% the words of William Tyndale, retweeted without direct credit being given. In fact, they sometimes return to Tyndale even against their base text. Yet here, they have demonstrably and intentionally rejected him. The KJV NT, while using “love” for most uses of agape, has “charity” for 29 of those uses. And this can surely be no accident, nor can they be unaware of the historic and public disputes of Tyndale and More.

Why bring charity back, after Tyndale fought so hard, at such cost, to exclude it?

Charity Through A Century

At this point, some kind of visual history of the frequency of the word’s usage might prove helpful. If we take the century from 1550-1650 and chart the uses of Charity, the results are revealing, (see the NgRam chart);

Notably, the word seems to have enjoyed a very brief stint of favor just as the 1572 revision to the Bishop’s Bible would have been worked on (not surprisingly, with the spelling the Bishops’ Bible used – see below), then another and larger one right at the time the revision to the 1602 Bishop’s Bible (the KJV) was being worked on (with the KJV spelling), and then a small spurt for a few short years just after its release, before slipping back into relative oblivion. Obviously, the stats here are limited, and provide no way to parse out biblical citations verses other uses. (And only examination of each result would show its use in context).

This is all the more striking when we compare it in the same period to the broader love, at which point, charity all but relatively disappears, with a notable decline in love to almost non-usage just as the KJV was being worked on;

If “charity” as a common synonym for love was not obscure when the KJV was printed, it clearly was within a few short years of that printing. The results might suggest that for one small decade or so, Charity could have been legitimately understood as something broader, perhaps, than giving to the poor. In this small window of time, perhaps they even overlapped as almost synonymous. The window was clearly small, and it passed quickly, lasting for only the window of time in which the KJV had the misfortune of being first worked on.

Charity in the Bible Today?

This raises the question of whether charity might be fitting English today for these biblical texts. One could make an argument that the KJV has itself so shaped the English language that it is now fitting, conveying a distinctly Christian notion (see the OED entry below). Others are more skeptical. C. S. Lewis, that master of the English language and its history, took up the question of what the word means in modern usage;

First, as to the meaning of the word. ‘Charity’ now means simply what used to be called ‘alms’—that is, giving to the poor. Originally it had a much wider meaning. (You can see how it got the modern sense. If a man has ‘charity’, giving to the poor is one of the most obvious things he does, and so people came to talk as if that were the whole of charity. In the same way, ‘rhyme’ is the most obvious thing about poetry, and so people come to mean by ‘poetry’ simply rhyme and nothing more.) Charity means ‘Love, in the Christian sense’. But love, in the Christian sense, does not mean an emotion. It is a state not of the feelings but of the will; that state of the will which we have naturally about ourselves, and must learn to have about other people.

—C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: HarperOne, 2001), 129.

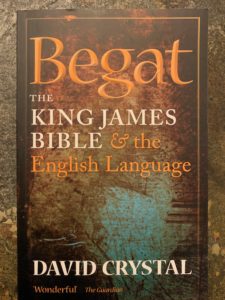

David Crystal (a contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary) likewise offers some hesitation;

The meaning of charity has weakened somewhat over the centuries, so that it now includes such notions as benevolence and fair-mindedness. It has sometimes even acquired negative connotations, as in the phrase cold as charity, especially heard in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, referring to the unfeeling way that some public charities were administered. The proverbial expression charity begins at home is often used in a self-serving context. Today, charity shops, Charity Commissioners, and other such phrases have added an institutionalized tone to the word.

Notwithstanding St Paul’s reiterated use in 1 Corinthians 13 (ending with And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity), anyone these days wanting to emphasize the emotional force originally carried by this word would do better to use love. The point is well illustrated in John 15: 13, where the use of charity would denude the sentence of its poignancy:

Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.

This formulation has carried the day. The first part competed with Douai-Rheims (Greater love than this no man hath), Tyndale and Geneva (Greater love than this hath no man), and Wycliffe (No man hath more love than this). The second part competed with Wycliffe (put for lay down) and Tyndale/ Geneva (bestow for lay down). There is still some stylistic variation today, but Greater love hath no man than this is the favourite expression, often summarized as No greater love.

Begat, The King Jame Bible And The English Language, kindle locations 3317-3333

If one thinks of that great Bard of love, William Shakespeare, his works put the matter into some historical perspective not far removed from the KJV. In the playright’s works, (the Folger editions), a quick search shows that while “love” occurs literally thousands of times, “charity’ occurs a mere three-score times, and often even in those rare uses clearly as a reference to almsgiving. For example, when Katherine in the Taming of the Shrew exclaims,

Beggars that come unto my father’s door

Upon entreaty have a present alms.

If not, elsewhere they meet with charity.

She equates charity with Almsgiving. For Shakespeare, charity is a weak and lifeless thing, usually referring to the act of almsgiving, but with no inherent notion of feeling, or passion. One may see the difference when, in Love’s Labour Lost, Longaville comes forward and pontificates,

Dumaine, thy love is far from charity.

A woman’s love, if only an act of “charity” or an act of pity wherein she condescends to an undeserving poor dupe, is a poor substitute for real love. “Charity” was simply too passionless a word, and too connected specifically to almsgiving, to find any real place in the Bard’s sonnets of love. He was speaking of a thing with a much higher affect.

In fact, that the KJV translators themselves shared a rather similar view seems clear. In a sermon on Tithing from Deut. 26, Thomas Harrison explains pedantically,

‘Tis due to Him…as a royall revenue….I wish triall were made whether it may not be proved (if the point were well studied, but I shall only hint it) that the tenth part (or other proportion) of every mans increase, acquisitions, improvements, and incoms is due unto the Lord even to this day: I am farre from thinking or saying that it is due unto the Ministry or to any sort of men, but that it is due and ought to be dedicated to God, and to the everlasting Priesthood of our Lord Jesus Christ, by way of thankfull acknowledgement to God for the same, a tenth which even the Ministers and the Glebe it self ought to pay, and so ought to be expended in the supporting of publick worship, in the relieving of the poore at home and abroad, under the rage of persecution in other Countries, and in the education of poore Children, the advancement of Learning (that inestimable Jewell) and other pious uses, and would every man that abounds make such a purse and account it depositum pietatis, as a sacred treasury or Corban not to be opened but for pious uses; how many necessitous parents, perishing orphans, poore aged people, persons ruined by fire, shipwrack, or the like, might speedily be releived? there is no pious person but judges, something due this way, and the holy Ghost calls even a mans charity due debt, Prov. 3.27. Withhold not good from them to whom it is due, when it is in the power of thine hand to do it. Say not unto thy neighbour, Go and come again, and to morrow I will give, when thou hast it by thee, verse 28. What we call giving, God calls paying; what we call charity, He counts due debt; all the question is about the quantum, how much ought thus to be dedicated to God, and to fix it upon the tenth part; is neither Popish nor Legall, or Jewish, but a known truth, or duty long before the oldest of these was heard of in the world; this was no naturall but an adoptive Child of Moses, nor was it a Type or Ceremony as sacrificing was (which was also before the Law) for then there must be some spirituall substance tiped out by it, but it was practised by the light of nature and law of reason, morall Law, and Law of Nations every where. Why else did Abraham Gen. 14.20. Pay tythes to Melchisedec, the great Representee of Christ, who is brought upon the stage like a man dropt out of the Clouds, only to shadow out Christ, as if he had neither Father nor Mother, birth nor death, Heb. 7.2.

—Thomas Harrison, Topica Sacra: Spiritual Logick: Some Brief Hints and Helps to Faith, Meditation, and Prayer, Comfort and Holiness. / Communicated at Christ-Church, Dublin, in Ireland. By T.H. Minister of the Gospel, Early English Books Online (London: Printed for Francis Titon, and are to be sold at the sign of the three Daggers in Fleet-street, 1658), 158–161.

“What we call giving, God calls paying; what we call charity, He counts due debt.” That’s the lifeless and passionless view of Harrison about the word, which here means giving to the poor, and can be included as part of paying tithe to the church.

No wonder Tyndale objected that this is clearly not what Paul was talking about.

I strongly prefer love, with Tyndale, and with more modern masters of the English language like Crystal and Lewis. Bill Cooper, in a review in the Tyndale Society Journal, raised the question of why, in I Cor. 13 in particular,

Tyndale’s and Coverdale’s love (translated from the Greek agape) was subverted and replaced in the KJV by Jerome’s charity. As was known by all on the KJV Committee, charity is entirely a mistranslation of agape, yet it has grand ecclesiastical ramifications. Charity is a monetary commodity (where love is not), and can therefore be bought and sold on the market of good works and merit. Instead of Tyndale’s love covering a multitude of sins, it is the Roman charity that ‘does it’ for the faithful, who thus must earn their sal- vation by good works. It was, in short, a deliberate return to the ways of the Latin church.

He goes on to point out that this was done by men (the KJV Translators) “who would not have been unaware of the important differences between the two words, nor their immense ramifications,” and concludes that the revival of charity in the KJV is, “after all, and in the opinion of many, the one great flaw in the KJV.”

An Artificial Distinction Not Grounded In The Biblical Text

But perhaps the strongest reason to object to “charity” in the KJV today is that it creates a distinction between “love” and “charity” that is not consistent or exegetically defensible. It is sometimes claimed that “charity” is used whenever “brotherly” love is in view, while “love” is used when other kinds of love (for God, or a spouse) are in view. See also here, or here, edit – or the article I just read here. Others claim that “charity” is used when a love of action or behavior is in view, while “love,” apparently, refers only to an emotion, as here. Thus, the KJV is actually more accurate, it is claimed, in making this distinction.

Perhaps the ablest voice defending the KJV here is that of William Burgon, who was always ready to step up and champion the KJV against any changes made by the 1881 Revisers. Burgon turns his attention to, “the calamitous fate which has befallen certain other words of infinitely greater importance,” in their work, and writes,

And first for Ἀγάπη—a substantive noun unknown to the heathen, even as the sentiment which the word expresses proves to be a grace of purely Christian growth. What else but a real calamity would be the sentence of perpetual banishment passed by our Revisionists on “that most excellent gift, the gift of Charity ,” and the general substitution of “Love” in its place? Do not these learned men perceive that “Love” is not an equivalent term? Can they require to be told that, because of S. Paul’s exquisite and life-like portrait of “ Charity ,” and the use which has been made of the word in sacred literature in consequence, it has come to pass that the word “ Charity ” connotes many ideas to which the word “Love” is an entire stranger? that “Love,” on the contrary, has come to connote many unworthy notions which in “ Charity ” find no place at all? And if this be so, how can our Revisionists expect that we shall endure the loss of the name of the very choicest of the Christian graces,—and which, if it is nowhere to be found in Scripture, will presently come to be only traditionally known among mankind, and will in the end cease to be a term clearly understood? Have the Revisionists of 1881 considered how firmly this word “ Charity ” has established itself in the phraseology of the Church,—ancient, mediæval, modern,—as well as in our Book of Common Prayer? how thoroughly it has vindicated for itself the right of citizenship in the English language? how it has entered into our common vocabulary, and become one of the best understood of “household words”? Of what can they have been thinking when they deliberately obliterated from the thirteenth chapter of S. Paul’s 1st Epistle to the Corinthians the ninefold recurrence of the name of “that most excellent gift, the gift of Charity ”?

—Burgon, John William. The Revision Revised. Kindle Edition.

Burgon, of course, bases his argument primarily on how the KJV has influenced the English language after it. And that’s a valid point. Just not the one that matters. He does not so much as mention the long history of battles about the word between Catholics and Protestants. He complains about, “the sentence of perpetual banishment passed by our Revisionists” on the word, making the same mistake as the OED we will see below, assuming that charity was the reading of all English versions until 1881, as though the Revisers had been responsible for first banishing it. He ignores all English translations prior to 1602. William Tyndale’s name is not even mentioned, as though he had fought for nothing.

Tyndale has been totally forgotten, and his passions with him.

But the problem with all such claims is that they create a distinction between “charity” and “love” that clearly distorts the biblical text. A few arguments make this clear;

First, there is another Greek word altogether for the more specific concept of brotherly love, when required, which the KJV often explicitly translates, “Brotherly love” (Rom. 12:10; I Thess. 4:9; Heb. 13:1).

Second, often the KJV used “love” to translate the same Greek word, agape, when love for the brethren is clearly in view. For example, Paul clearly speaks of his own brotherly love for the Corinthians in II Cor. 2:4; 11:11; 12:15, and explicitly urges love for the expelled bother in II Cor. 2:8. He urges their love for him in II Cor. 8:7-8.

As to the claim that charity is used rather when a love of action is in view, one need only point to texts like Gal. 5:13, Eph. 1:15; 4:2; Col. 1:4; I Thess. 1:3; 3:12; James 2:8, and, explicitly, I John 3:18, where love alone conveys this idea. John writes, “My little children, let us not love in word, neither in tongue; but in deed and in truth.” He could not be more explicit that he means here a love of “deed.” And yet the KJV has love and not charity here. Peter speaks as clearly as possible urging, “unfeigned love of the brethren,” and commanding that “ye love one another with a pure heart fervently” (I Pet. 1:22). And yet, charity doesn’t make it into this verse in the KJV. The same could be said for I Pet. 2:17; 3:8; I John 3:11; 3:14; I John 4:7, 11, 12, 20, 2 John 5, 3 John 1.

The reality is, the use of “charity” in some passages where agape appears, and “love” in others, perpetuates a patently artificial and unbiblical distinction where the Greek text has no such distinction. And anyone demanding some kind of distinction between them will invariably face the problem that the KJV itself ignores their distinctions, making it an inferior product by their own parameters. As we saw last time, this distinction arose out of a desire to read almsgiving and works into the text where it wasn’t present. It was defended by those (like More) who didn’t like the justification by faith that Tyndale was advocating, and used these texts about “charity” as prooftexts to support justification by works. It simply is not a distinction present in the Greek text.

Examining The Primary Sources Related to the KJV

A number of primary resources related to the history and origins of the KJV are regularly used by scholars such as David Norton to investigate the KJV. A few are worth glancing at here to trace out the history of the insertion of charity.

The marginal notes of the KJV mention charity, as best I can tell, only at Romans 14:15.

John Bois, one of the translators of the KJV, in the notes he took during the General Assembly at Stationer’s Hall (where most of the final tweaks were put on the text), gives only one hint of even noting the differences, which is that at Jude 12, he writes out, “these are, when they banquet with you, spot, or rockes in your Love feasts.” No more discussion is evident at this later stage of the work, and the notice serves only to underscore what we know already from the regular use of Tyndale, Geneva, etc. by the Revisers, and that is that they are aware of Tyndale and his readings.

What of the earlier stages? The epistles (where almost every use of charity occurs in the KJV) were commissioned to the Second Westminster Company. Looking over their draft work (Ms. 98, which I had the privilege to spend a day with, and photographed thoroughly a few months ago), we find that, while a few passages have no text here (they apparently only penned text into their copy when they intended to alter the Bishops’ text), none of the KJV “charity” passages present have anything other than “charity,” not even Jude 12. The resulting realization is that there was, even at the earlier stages of the work, for this company at least, no evident discussion or overt attempt to do anything other than what was the final result here. Which strikes us as odd given how rare charity is outside the work of this company (for example, in the Gospels, Acts, and the OT). The 2nd Westminster Company seems quite convinced of what it has done.

The OED has a note specifically dedicated to the word charity as used to render the NT word, via the Vulgate;

The Greek word for ‘love’ in the New Testament (occasionally also in the Septuagint) is ἀγάπη , from root of verb ἀγαπᾶν ‘to treat with affectionate regard’, ‘to love’; in the Vulgate, ἀγάπη is sometimes rendered by dilectio (noun of action < diligere to esteem highly, love), but most frequently by caritas , ‘dearness, love founded on esteem’ (never by amor ). Wyclif and the Rhemish version regularly rendered the Vulgate dilectio by ‘love’, caritas by ‘charity’. But the 16th cent. English versions from Tyndale to 1611, while rendering ἀγάπη sometimes ‘love’, sometimes ‘charity’, did not follow the dilectio and caritas of the Vulgate, but used ‘love’ more often (about 86 times), confining ‘charity’ to 26 passages in the Pauline and certain of the Catholic Epistles (not in 1 John), and the Apocalypse, where the sense is specifically 1c below. In the Revised Version 1881, ‘love’ has been substituted in all these instances, so that it now stands as the uniform rendering of ἀγάπη, to the elimination of the distinction of dilectio and caritas introduced by the Vulgate, and of ‘love’ and ‘charity’ of the 16th cent. versions.

The first definition of the OED and its third subheading further highlights that “charity” came into English Bibles via the Vulgate, and its overall treatment reveals that its most common usage today has quite a different meaning than might have been intended in the KJV;

1. Christian love: a word representing caritas of the Vulgate, as a frequent rendering of ἀγάπη in New Testament Greek. With various applications: as,

a. God’s love to man. (By early writers often identified with the Holy Spirit.) Obsolete

b. Man’s love of God and his neighbour, commanded as the fulfilling of the Law, Matt. xxii. 37, 39. Obsolete.

c. esp. The Christian love of one’s fellow human beings; Christian benignity of disposition expressing itself in Christ-like conduct: one of the ‘three Christian graces’, fully described by St. Paul, 1 Cor. xiii.

One of the chief current senses in devotional language, though hardly otherwise without qualification as ‘Christian charity’, etc. In the Revised Version, the word has disappeared, and love has been substituted.

d. In this sense often personified in poetic language, painting, sculpture, etc.

e. in, out of, charity: in or out of the Christian state of charity, or love and right feeling towards one’s fellow Christians.

f. In various phrases: see the quotations.

2.

a. Without any specially Christian associations: Love, kindness, affection, natural affection: now esp. with some notion of generous or spontaneous goodness.In Wyclif, representing caritas of the Vulgate, which (like ἀγάπη, ἀγάπησις) is used very generally in the Old Testament. In other cases influenced perhaps by Old French chierté, Latin caritas, or simply with generalized sense.

b. plural. Affections; feelings or acts of affection.

3.

a. A disposition to judge leniently and hopefully of the character, aims, and destinies of others, to make allowance for their apparent faults and shortcomings; large-heartedness. (But often it amounts barely to fair-mindedness towards people disapproved of or disliked, this being appraised as a magnanimous virtue.)Apparently a restricted sense of 1c, founded upon one of the special characteristics ascribed to Christian charity which ‘thinketh no evil’ 1 Cor. xiii. 6; cf. also 1 Pet. iv. 8 ‘Charity shall cover the multitude of sins’.

b. Fairness; equity. Obsolete.

4. Benevolence to one’s neighbours, especially to the poor; the practical beneficences in which this manifests itself.

a. as a feeling or disposition; charitableness.

b. as manifested in action: spec. alms-giving. Applied also to the public provision for the relief of the poor, which has largely taken the place of the almsgiving of individuals.

[Some would explain quot. 1154 as hospitality, or ‘agape Christianorum, convivium quo amici vel etiam pauperes excipiuntur’ (Du Cange).]

c. plural. Acts or works of charity to the poor.

5. That which is given in charity; alms.The phrase do one’s charity, in 4b, easily passed into give one’s charity.

6. A bequest, foundation, institution, etc., for the benefit of others, esp. of the poor or helpless.

The term, especially under the influence of legislative enactments, such as the statute on charitable uses 43 Eliz. c. 4, and the various modern Charitable Trusts Acts, has received a very wide application; in general now including institutions, with all manner of objects, for the help of those who are unable to help themselves, maintained by settled funds or voluntary contributions; the uses and restrictions of the term are however very arbitrary, and vary entirely according to fancy or the supposed needs of the moment; chief among the institutions included are hospitals, asylums, foundations for educational purposes, and for the periodical distribution of alms.

7. A refreshment dispensed in a monastic establishment between meals; a bever. (Apparently only a modern rendering of medieval Latin charitas in sense of ‘quævis extraordinaria refectio, maxime illa quæ fiebat extra prandium et cœnam in Monasterio.’ Du Cange.)

8. A popular name of the plant ‘Jacob’s ladder’, Polemonium cæruleum.

In my own experience, 3a, 4, 5, and 6, are by far the most common uses today. Notably, 1c is the one which would have to be argued to make the KJV contemporary, (and at that, it clearly represents an interpretive choice by the translators in 28 of the Greek word’s uses, not a distinction present in the Greek text itself), but I have a suspicion one could find few uses with that meaning that aren’t in, or directly influenced by, the KJV itself.

Early Protestant English Translations

Tyndale, as we have seen, searching the Logos edition, banished the noun charity entirely from his NT in both his major editions (he used the adverb only once, in Rom. 14:15). He would have no allowance for a Roman notion of works.

A quick search of the Logos edition of the Geneva Bible shows that the Genevan reformers followed suite – charitie is entirely absent from their Bible, save one use in Jude 12 (though it’s instructive to note how often charitie occurs in their heading and marginal notes, usually as an explanation of works of love, and even at times specifically distinct from love, as in the note at Is. 1:17).

Coverdale has charite only once, in Romans 14:15, searching the Logos edition.

Skimming an electronic edition of the Great Bible shows roughly the same.

As does a search of the Matthew’s Bible.

Charity was virtually unknown in these early Protestant translations (while being prolific in the Wycliffe translation of the Catholic Latin Vulgate).

It is now widely recognized that the KJV took the Bishops Bible as its base text, and revised it as little as was necessary, per Bancroft’s first rule for the Translators. Matthew Parker in the 1568 Bishop’s Bible, the initial printing, formally titled, The Holie Bible Conteynyng the Olde Testament and the Newe, (the Early English Books Online edition), while using charitie often in the headings, seems to have used charitie in the text only at Rom. 13:10 and Jude 12. I Corinthians 13 reads more like Tyndale. See it on the right.

As it turns out then, when the OED asserts that, “the 16th cent. English versions from Tyndale to 1611,” used charity in 26 passages in Paul, it is at best only telling part of the story, and perhaps even misleading. The historical reality is almost exactly the opposite of the picture one would assume from their words. All the more so when the OED astonishingly claims (like Burgon) that it was the 1881 RV that displaced charity, as though Tyndale and his campaign against the word had never even existed! So much the worse for the forgotten Tyndale.

In reality, Tyndale banished charity from the English Bible, and it remained in almost total and complete exile through all of the major Protestant English translations. The KJV was not continuing a long tradition that the 1881 ERV would finally reject; it was rejecting a long tradition that Tyndale had begun, and others had long perpetuated.

The Source

So how did we get from that to the AV revival of charity? The answer, in part, lies in the realization that it was specifically the 1602 edition of the Bishops Bible which served as the basis for the AV which was a revision of that text, not the earlier editions, as has been conclusively shown by Vance.

When we examine the 1602 edition (I have not examined any intervening editions, and the text may have changed as early as the 1572 – Vance suggests in passing that the 1572 first introduced the word charity in I Cor. 13 at least), we realize it has come straight into the KJV. The 1602 has charitie or its similar forms at Rom. 14:15, I Cor. 8:1; 13:1-13; 14:1; 16:14; Col. 3:14; I Thess. 3:6; II Thess. 1:3; I Tim. 1:5; 2:15; 4:12; II Tim. 2:22; 3:10; Titus 2:1; I Pet. 4:8; 5:14; II Pet. 1:7; III John 6; Jude 12; Rev. 2:19. That is, in the exact places where the AV also has the word. (And perhaps some others besides – I have not searched the whole text, though preliminary spot checks show it having love in most places I would suspect it to differ, like Rom. 5:8; 13:10). Tyndale’s great poem to love has become the odd ode to charity already in Parker’s revisions.

What changed at some point between 1568 and 1602 that directly caused the restoration of charity to the English text remains to be investigated.

The KJV translators (or better, revisers of the Bishops Bible) had before them the options of many or even most of the English translations that had gone before them. Yet, without so much as a word, they retained the wording not of Tyndale, or any of the later Protestant translations, not the wording of the original Bishops’s text, but exactly the word used in each place in the 1602 revision of the Bishop’s text.

Notably, with the one exception of Rev. 2:19, every other use of charity is in a part of the text handled by the Second Westminster Company. “Love” seemed to work just fine in every other place for every other company. This Company alone preferred “charity” in places where the Bishop’s text had it. Headed by William Barlow as President, this company had some of the strongest anti-Puritan sentiments of any that worked on the KJV. Barlow himself had made his disdain for the Puritans clear from the very start of the Hampton Court Conference that birthed the KJV, and his account of the Conference drips with hatred for them. In the Second Westminster Company’s work, apparently, Separatist ideas could be allowed no pass. And Rule 1a and 3 have apparently given them license to snub Tyndale.

And when we turn to the KJV preface, penned by Miles Smith, at least one possible reason thus suggests itself. (See a detailed explanation of this section and the whole preface here). In a brief note towards the end, under the last heading of the Preface, they explain,

Lastly, we have on the one side avoided the scrupulosity of the Puritans, who leave the old Ecclesiastical words, and betake them to other, as when they put washing for Baptism, and Congregation instead of Church: as also on the other side we have shunned the obscurity of the Papists, in their Azimes, Tunike, Rational, Holocausts, Prœpuce, Pasche, and a number of such like, whereof their late translation is full, and that of purpose to darken the sense, that since they must needs translate the Bible, yet by the language thereof it may be kept from being understood. (Scrivener, CPB)

This quiet admission, which almost escapes notice, perhaps explains as best as anything else we can find. Here are several of Tyndale’s very batch of explosive words, and while “love” is not mentioned directly, their “as” with the examples of baptism and church might well stand for the whole group. Tyndale’s words got him killed, a fate he faced with courage. But from Tyndale’s perspective at least, the King, on the other hand, has fallen prey to fame. Study divorced from passion was thought better. The King wants little to do with Tyndale and his battles. The Puritans have had little or no say in the work, short of the fact that they asked for it (though they didn’t actually want it, and are now stuck with it against their wishes, for theirs was, “but a poore and empty shift”).

And in a quite literal way, love has been lost.

All that dangerous and nasty business that Tyndale has fought for has been let go as too extreme, too messy, and too, well, radical. They judge Tyndale far too concerned to follow the dictates of his conscience. He should have cared less. They do. Like the Puritans of their day, he was too “scrupulous.” He would think they have hidden his blood-wrought legacy behind a wall of easy compromise. From his stake, he might claim, with prayerful lips, that they have sacrificed flippantly what he had fought for so valiantly. Tyndale was willing to die for his words. The KJV translators instead at best sit silently by while he is burned.

The annual reckoning has come to the King. It turns out that all that protestation, said over and over, was little more than empty blunder.

Love’s labor has been lost.

William Tyndale And God’s English Voice

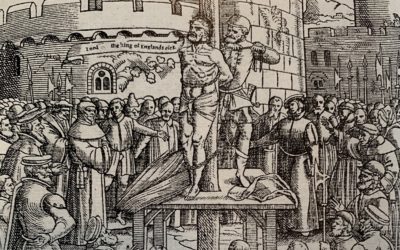

“Lord! open the king of England’s eyes!”

In 16th century Europe, a prayer like this spoken out loud to God was bold no matter who spoke it. Such a prayer borders on both blasphemy and treason – who could dare suggest that the king is blind, or worse yet, that God is not on his side? But the striking prayer captivates us even more as we watch on while it is cried out by a man, on October 6th, 1536, tied to a stake. He is finally strangled with a rope, as though in a last effort to silence his dangerous voice. His body now silent and limp, he is then burned at that same stake.

The man, of course, is William Tyndale (rhymes with kindle). After 18 months in prison, he had been in August officially condemned as a heretic, stripped of his priesthood, and handed over to the authorities for punishment. His crime? Heresy. But hidden behind that charge was his real crime – giving the common English people the Bible in their own tongue, and, to boot, Luther’s Reformation theology along with it.

That’s how the story ends. But how did it begin?

Tyndale And The Birth Of A Dream

We don’t know when he (or his two brothers) was born exactly – sometime between 1492-1495. David Teems notes with exasperation, “We know more about the sound of his last name than we do the year he was born, who his parents were, where he grew up, how old he was when he attended Oxford, and whether or not he attended Cambridge as certain histories imply, or why there seems to have been two family names.”

We do know that in 1508 he entered Magdalen College at Oxford, (some say, at the age of 12), where he took his B.A. on July 4th, 1512, and his M.A. two years later. In 1521, he found himself working in Gloucestershire, serving as a tutor to the children at Little Sodbury, the estate of the wealthy Sir John Walsh. (See his room on the left, image from Christian History Magazine.) Here, at some point, he developed a singular passion that would consume his life. He gave himself more and more to the study of the Greek New Testament of Erasmus. And he became increasingly of the conviction that this was a book – the book – by which God would speak to the common people. John Foxe (of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, properly titled, Acts and Monuments of These Latter and Perilous Days, Touching Matters of the Church, Wherein Are Comprehended and Described the Great Persecutions Horrible Troubles, That Have Bene Wrought and Practiced by the Romish Prelates, Specially in This Realm of England and Scotland, from the Year of Our Lord, a Thousand unto the Time Now Present. Gathered and Collected According to the True Copies Writings Certificatory, or The Acts and Monuments for short) recounts a small story of a conversation during this time that shows us this passion up close, in Tyndale’s own words (spelling and punctuation updated);

And soon after, Master Tyndale happened to be in the company of a learned man. And in coming and disputing with him, drove him to that issue that the learned man said, “We were better be without God’s law, than the Pope’s.” Master Tyndale, hearing that, answered him, “I defy the Pope and all his laws,” and said, “If God spare my life, ere many years, I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost.”

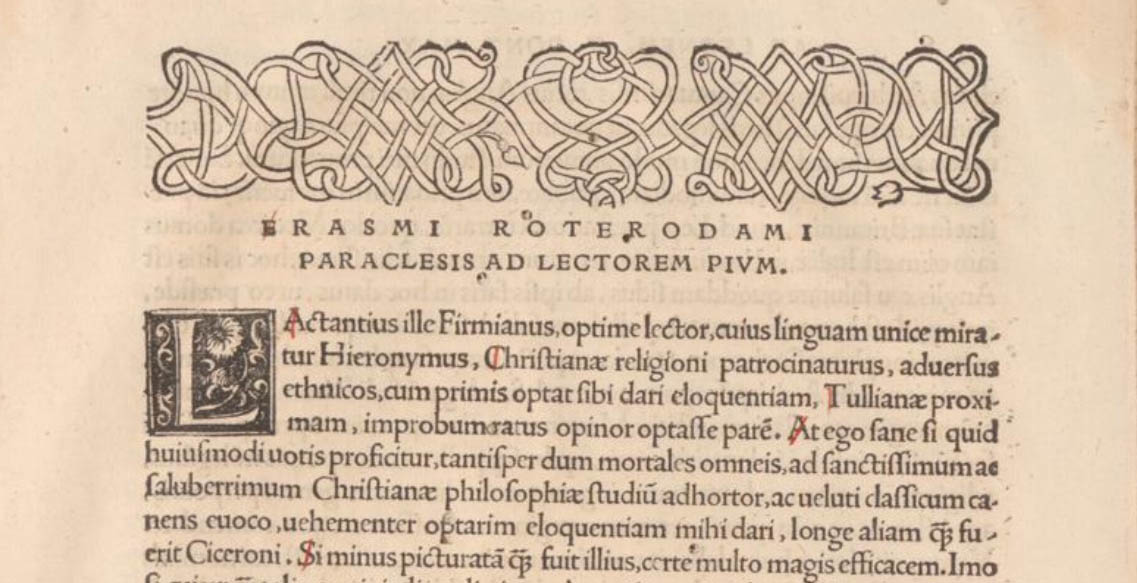

The passion of the Dutch Humanist scholar, Erasmus of Rotterdam, spills out of Tyndale’s mouth. Erasmus had written in his Paraclesis, at the front of his 1516 edition of the Latin/Greek NT,

I disagree entirely with those who do not want divine literature to be translated into the vernacular tongues and read by ordinary people, as if Christ taught such convoluted doctrine that it could be understood only by a handful of theologians, and then with difficulty; or as if the defense of the Christian religion were contingent on this, that it remain unknown. Perhaps it is expedient to conceal the secrets of kings, but Christ desires his mysteries to be known as widely as possible. I would like every woman to read the Gospel, to read the Epistles of Paul. And oh, that these books were translated into every tongue of every land so that not only the Scots and the Irish but Turks and Saracens too could read and get to know them. The first stage, unquestionably, is to get to know them – somehow or other. Granted that many people would laugh; yet some would be won over. How I wish that the farmer at his plough would chant some passage from these books, that the weaver at his shuttles would sing something from them; that the traveller would relieve the tedium of his journey with stories of this kind; that all the discussions of all Christians would start from these books…

—Erasmus of Rotterdam (CWE 41)

Clearly Tyndale has not only lived in the Greek biblical text of Erasmus – he has been stirred by its prefatory material as well. Erasmus was a man of words. What he expressed as wish – perhaps even prayer – Tyndale, a man of action if nothing else, will make a life goal.

The Bible in England had long been somewhat obscured in the Latin of the Vulgate. This doesn’t mean it wasn’t accessible at all. The people had numerous ways of imbibing some parts of Scripture in public liturgy. But it did mean that setting down to read it for one’s self, in one’s own tongue, was not, for most common people, even an option. In much (most?) of the world at the time, it would not have been such a problem to give the common people a Bible in their own language. But in England, in just this same window of time, it happened to still be illegal.

Perhaps it is expedient to conceal the secrets of kings, but Christ desires his mysteries to be known as widely as possible.

—Erasmus of Rotterdam

The Constitutions of Oxford from 1408 were still in force. In the wake of the work of that arch-heretic John Wycliffe, Archbishop Thomas Arundel had declared that, “The translation of the text of Holy Scripture out of one tongue into another is a dangerous thing,” and decreed against the Lollards that,

…Therefore we enact and ordain that no one henceforth do by his own authority translate any text of Holy Scripture into the English tongue or any other by way of book, pamphlet, or treatise. Nor let any such book, pamphlet, or treatise now lately composed in the time of John Wicklif aforesaid, or since, or hereafter to be composed, be read in whole or in part, in public or in private, under pain of the greater excommunication….Let him that do contrary be punished in the same manner as a supporter of heresy and error.

However dangerous, his passion to take the original Greek and Hebrew texts and put them into English consumed him. He soon realized that this was no easy task. He initially attempted to follow legal channels to produce an authorized English Bible. But such was not to be allowed. As Tyndale himself noted in the later preface to his Pentateuch, he, “understood at the last not only that there was no room in my lord of London’s palace to translate the new Testament, but also that there was no place to do it in all England, as experience doth now openly declare.” The powers that be in England had no wish for the people to read the Bible in their own tongue. Such a dream was dangerous.

Tyndale was equipped as few could be to accomplish his dream. He had learned Greek at Oxford, then Hebrew, and became eventually what we could call a multi-linguistic genius. These were not aimless pursuits – they were servants to his grander cause. Tyndale Scholar and biographer David Daniell notes;

William Tyndale was a most remarkable scholar and linguist, whose eight languages included skill in Greek and Hebrew far above the ordinary for an Englishman of the time—indeed, Hebrew was virtually unknown in England. His unsurpassed ability was to work as a translator with the sounds and rhythms as well as the senses of English, to create unforgettable words, phrases, paragraphs and chapters, and to do so in a way that, again unusually for the time, is still, even today, direct and living: newspaper headlines still quote Tyndale, though unknowingly, and he has reached more people than even Shakespeare. At the centre of it all for him was his root in the deepest heart of New Testament theology, a faith of the sort that can, and did, move mountains.

William Tyndale As Pioneer Translator

But his was a road that was not only hard, it was also new; he was blazing a new path. Snippets of English Scripture had existed, and of course, Wycliffe’s versions existed in English. But Wycliffe and the Lollards had translated from Latin into English. Caught up in the age of the Renaissance, Tyndale’s passion was to give the original Greek and Hebrew in English. Here, as he would note, he, “had no man to counterfeit, neither was helped with English of any that had interpreted the same or such like thing in the scripture beforetime.” Tyndale was fashioning a new translation, and it was not a road “less traveled” so much as bush through which a trail needed to be cut.

The 1525 Cologne Fragment

In 1525, from the press in Cologne, he begun to print his NT. He reportedly got as far as part of Mark. But he was interrupted, and unable to complete the work, as the Cologne authorities came to arrest him and confiscate his work. All that remains from this work today is Matthew 1-22 and his prologue, in a single fragment. It is the first time in an extant work that we can hear his voice in print. Daniell notes that most of this text of Matt. 1-22 came unchanged into his later edition But he urges us not to miss the significance of something much more important that is happening;

…the English into which Tyndale is translating has a special quality for the time, being the simple, direct form of the spoken language, with a dignity and harmony that make it perfect for what it is doing. Tyndale is in the process of giving us a Bible language. Luther is often praised for having given, in the ‘September Bible’, a language to the emerging German nation. In his Bible translations, Tyndale’s conscious use of everyday words, without inversions, in a neutral word-order, and his wonderful ear for rhythmic patterns, gave to English not only a Bible language, but a new prose.

Marginal Notes

While the later printed full NT has no marginal notes, this early fragment from Cologne has some 90 of them just in the extant 22 chapters of Matthew. Had Tyndale continued on with this original plan in his full NT later, we can only imagine the wealth of information we might have from his notes.

The 1526 NT

In 1526, at Worms, Tyndale finally completed printing of his entire NT. Here, Daniell notes, for the first time, was the original Greek NT in English;

We must not lose sight of the extraordinary quality of that first printed New Testament in English, as it was welcomed and read in London and southern and eastern England. Here was suddenly the complete New Testament, all twenty-seven books, the four Gospels, the Acts, the twenty-one Epistles and Revelation, in very portable form, clearly printed. Here was the original Greek, in English. The bare text itself was complete, and without an iota of allegorising commentary. Everything that had been originally written was here, to be read freely without addition or subtraction. The only constraints were the implicit command to read it, and in reading to relate one text to another, even one book to another, so that the high theology of Paul in the Epistles could be understood in relation to the words and work of Jesus in the Gospels.

Yet Tyndale reads like a modern text;

What still strikes a late-twentieth-century reader is how modern it is….both vocabulary and syntax are not only recognisable today, they still belong to today’s language….Tyndale goes for clear, everyday, spoken, English. Because it was largely the current language of his day, it remains largely a current language of ours. He is not out to make antiquarian effects, as the Authorised Version did, for partly political reasons. The result is that Tyndale usually feels more modern than the Authorised Version, though that revision was made nearly a century later.

The King James Bible of 1611 would tend to Latinize the English text, making it more elegant, but also more ambiguous, less direct, and less clear. Tyndale, by contrast, was direct, forceful, and above all, clear. This was no accident – it was by theological conviction. Daniell explains, “Central to Tyndale’s insistence on the need for the Scriptures in English was his grasp that Paul had to be understood in relation to each reader’s salvation, and he needed there, above all, to be clear.”

As the last sheets came off the press, Tyndale’s primary dream was realized. The Bible (the NT at least) had come finally into the common tongue.

God had learned to speak English.

As Daniell concludes, “The boy that driveth the plough had got his Scripture.”

Tyndale’s English

Daniell notes that, “With this volume, Tyndale gave us a Bible language.” David Teems explains that, “Today, in our common English, we speak Tyndale more than we do Shakespeare. And the King James Bible with its high step and its lovely old voice gets the applause that rightfully belongs to William Tyndale.” Teems goes on to point out that;

If you have ever bid someone a warm Godspeed, you have William Tyndale to thank for the blessing. And network is not a word you might have expected to hear in 1530. Tyndale set these two words adrift into the English language almost five hundred years ago, and with them words like Jehovah, thanksgiving, passover, intercession, holy place, atonement, Mercy seat, judgement seat, chasten, impure, longed, apostleship, brotherly, sorcerer, whoremonger, viper, and godless. This is just a start. An impressive start, certainly, and there are literally hundreds more.

A long list of expressions come into English as virgin speech through Tyndale. Teems lists just a small sample of examples (a much longer list of words, also incomplete, is included in an appendix to his work);

- Behold the lamb of God

- I am the way, the truth, and the life

- In my father’s house are many mansions

- For thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory

- Seek, and ye shall find

- With God all things are possible

- In him we live, move, and have our being

- Be not weary in well doing

- Looking unto Jesus, the author and finisher of our faith

- Behold, I stand at the door and knock

- Let not your hearts be troubled

- The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak

- For my yoke is easy and my burden is light

- Fight the good fight

Teems asks us to picture what such words must have meant to those who first heard them;

Imagine hearing these words for the first time, especially after being denied this most primary exchange for centuries. God is no longer hoarded or kept at a distance. He is flush, lucent. And he sounds like you sound. He uses your words, your patterns and rhythms. There is no longer a wall, or a divide, at least not by way of speech. The generosity alone is overwhelming.

—David Teems, Tyndale: The Man Who Gave God An English Voice

Tyndale in his text urges his reader to listen closely – God is speaking in these pages. Hear him with no mixture. Hear him speak your own language. In his “W.T. To The Reader,” at the back of the work, he writes, “Give diligence, reader, I exhort thee, that thou come with a pure mind, and, as the scripture saith, with a single eye, unto the words of health and of eternal life; by the which, if we repent and believe them, we are born anew, created afresh, and enjoy the fruits of the blood of Christ….”

He reminds the reader that should they find fault, they should keep in mind that he has interpreted the text, according to his gifts, as far as God gave him. His conscience is clear. And if any “rudeness” be found in the text, “consider how that I had no man to counterfeit, neither was helped with English of any that had interpreted the same or such like thing in the scripture beforetime.” Pioneers always make some missteps. Tyndale’s text is not the final word – no English translation ever could be, from his point of view. Rather, the reader should, “Count it as a thing not having his full shape, but as it were born before his time, even as a thing begun rather than finished.” Translation is, for Tyndale, always somewhat provisional. It can always be made better.

A Brief Introduction to the Life and Ministry of William Tyndale from Crossway on Vimeo.

Daniell notes in the introduction to his modern-spelling edition of the 1534 NT of Tyndale, “Astonishment is still voiced that the dignitaries who prepared the 1611 Authorized Version for King James spoke so often with one voice – apparently miraculously. Of course they did: the voice (never acknowledged by them) was Tyndale’s. Much of the New Testament in the 1611 Authorized Version (King James Version) came directly from Tyndale…” One more precise study showed that the NT of the KJV is 83.7% the work of William Tyndale, retweeted, without direct credit given. Watch an illuminating interview with Daniell about Tyndale here.

Tyndale will continue to work, and continue to write. In our next post, we will examine his various non-biblical writings, his work on the OT text, and his work as a Bible “reviser” improving his text.

Tyndale’s story is not over yet.

Love’s Labor Lost: Charity Banished By Tyndale

“I’m going to read to you the very touchstone of embellished prose in English literature.” That’s how Leland Ryken starts the day in his class when he teaches prose styles in 17th century English literature. He then reads to his students from I Corinthians 13 in the King James Bible. (See, The Legacy of the King James Bible, pg. 151). This poem in praise of love is one of the most well known in the Bible, quoted commonly at weddings, printed on picture frames, and embedded in the English speaking conscience. Surely, any English reader can discover why by merely reading sections of the passage aloud;

Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge: and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have no charity, I am nothing. And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burnt, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing. Charity suffereth long, and is kind: charity envieth not: charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up, doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil, rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth: beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things. Charity never faileth: but whether there be prophecies, they shall fail; whether there be tongues, they shall cease…And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three, but the greatest of these is charity.

(David Norton, ed., NCPB, 1 Co 13:1–13)

Here is the King of our English Bibles which we know so well, standing sure in all his majestic beauty. He is a brave conquerer whose edict shall strongly stand in force. He will not succumb. But we must ask – from whence came this oratorical ode to charity? That is, more specifically, why is it an ode to charity and not an ode to love?

The story, as so often, starts with William Tyndale in the early part of the 16th century.

The Weighty Words Of Reformation

The great passion of William Tyndale’s life was to put the Bible into English. Unlike previous attempts (like those by Wycliff and the Lollards), Tyndale wanted to put the Greek text of the NT itself (not the Latin Vulgate) into English. The people deserved no less. As he did so, he created in some cases original renderings, and in others gave certain English words a place in the Bible they had never had before (effectively creating a new kind of English, sometimes later called “Bible English”). David Daniell, the great Tyndale scholar and biographer, explains;

Apart from manuscript translations into English from the Latin, made at the time of Chaucer, and linked with the Lollards, the Bible had been only in that Latin translation made a thousand years before, and few could understand it. Tyndale, before he left England for his life’s work [the very first translation of the Greek NT into English], said to a learned man, ‘If God spare my life, ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost.’ He succeeded.

Daniell, David. William Tyndale: A Biography (p. 1).

At some points, Tyndale’s choice of English words showed a significant departure from the vocabulary that had become standard in those passages through the influence of the Latin Vulgate (primarily via Wycliffe). A few of these words became theological “hotspots” of controversy in the Catholic/Lutheran debates. Indeed, Tyndale’s passion to put the original Greek text into clear English comes most to the fore where he thought medieval catholicism had obscured the text, or imported what he thought to be wrong theology into it.

If God spare my life, ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost.

William Tyndale

In fact, the whole battle of the English Reformation can be seen, from one angle (and it is not the only angle), as a battle about which words should have a place in the English Bible, and how much the Latin should be allowed to shape the English Bible. David Norton illustrates how the importance of vocabulary was central to Reformation concerns by the story of an early attempt that would ultimately give the Church the Bishops’ Bible;

The Bible in English was part of the larger battle, political as much as theological, for the English Reformation. The clergy’s political allegiance might be relatively easily diverted from Rome to London, but beliefs were not so readily changed. By no means all the clergy were enthusiasts for the vernacular Bible: if they could not suppress it they could at least attempt to make it more acceptable to themselves, that is, more like the Vulgate. An attempt to do this was made in 1542. Though it came to nothing, it remains of interest because it gives further evidence of just how much the question of English vocabulary was tied up with larger issues. In parliament the archbishop ‘asked members individually whether without scandal, error and manifest offence of Christ’s faithful they voted to retain the Great Bible in the English speech. The majority resolved that the said Bible could not be retained until first duly purged and examined side by side with the [Latin] Bible commonly read in the English Church’. The work went into committee, and the last one hears of it is a list of Latin words which Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, ‘desired for their germane and native meaning and for the majesty of their matter might be retained as far as possible in their own nature or be turned into English speech as closely as possible’ (Pollard, p. 117). Clearly Gardiner would have preferred these meaningful and majestic words to remain untouched.

A History of the English Bible as Literature, pg. 35

Norton concludes that, “The manner of English translation was a fundamental issue of the Reformation.” He might be accused of slight exaggeration, but he is clearly not entirely wrong. Words matter, and the question of which precise words deserved to have a place in the English Bible were core to the Reformation question in England.

One of the words that became a hotspot was the way Tyndale translated the Greek word agape, in I Cor. 13 (and some other places), as love rather than the word that had been common, which was charity. Tyndale was by no means the first to use the English word love. But he did create the first English translation that exclusively used love instead of using a mix of love and Charity. To understand what was going on we must back up in the story a thousand years.

A Brief History of Charity

When Jerome translated the Greek NT into Latin (or started a translation that others later completed), he had sometimes rendered the Greek word agape as caritas, and other times rendered it as dilectio. This was a matter of sheer interpretation. The Greek displayed no clear difference at these points.

Not all agreed that there should be any distinction. Augustine argued (which shows that he had someone to argue with) that there was no difference in meaning between the Latin words. Citing numerous passages, he concludes, “But we wished to show that the Scriptures of our religion, whose authority we prefer to all writings whatsoever, make no distinction between amor, dilectio, and caritas; and we have already shown that amor is used in a good connection” (The City of God, XIV.7.1, NPNF).

Nonetheless, despite Augustines objections, the Latin text retained a difference (seen still for example in Biblia Sacra Iuxta Vulgatam Versionem, which uses caritas 105 times, and dilectio 43) that would be felt more strongly as time went on, but one that was not based on the Greek text. This distinction came into the English Bible by way of Wycliffe and the Lollards. A quick search of the Logos edition shows that loue occurs 96 times in the NT, while charite occurs some 94.

The distinction Augustine opposed so firmly had become part of common English theology.

Tyndale’s Bout With Charity

Tyndale was convinced that bringing this distinction into English missed the Greek text. His passion was, as always, to go back to the Greek, and to give that text to the English reader without a Latin or ecclesiastical intermediary. Thus, Tyndale spoke of “love” in I Cor. 13. In fact, with one minor exception, Tyndale spoke of “love” in every place the Greek NT has agape. He cast out charity entirely from the NT. Love was the reading of the Greek text, which had no distinction.

It turns out, then, that this was one of that small handful of words that Tyndale was convinced had imported bad theology into the Bible. Daniell explains that Tyndale’s approach to some of these words was part of his support of the Reformation project. It was drawn from his passion to let the Greek NT itself speak. In contrast to earlier translations, in Tyndale’s completed NT translation in 1526, “There is strikingly no reference to the Church, to what the pope, the bishops or the priests teach; nor to the ceremonies of the Church as necessities for salvation; nor to the tomes of casuistry erected on each syllable of Scripture down the centuries; nor to the element, taught as essential, of doing good works, especially in giving money to priests, monks and friars. All you need is this New Testament and a believing heart.”

But Tyndale, Daniell notes, is not being perverse. He translates presbuteros, as “senior,” (and later, “elder”) becuase that is what the Greek text says. He translated the word for the group of Christians together, ekklesia, correctly, a “congregation,” because the Greek word means simply “assembly” without overtones of apostolic succession. Tyndale, “avoids ‘church’ because it is not what the New Testament says.” He translates the Greek verb metanoeo, precisely as it means, “repent” rather than “do penance,” a rendering that has brought foreign connotations into the text. He likewise translates the verb exomologeo, which has the primary sense, “acknowledge, admit,” as “acknowledge” because no idea of confession to a priest is in the text. Finally, Daniell notes, “The Greek word agape is one of several words for ‘love’, so Tyndale prints ‘love’ (as in 1 Corinthians 13) and not ‘charity’.” Tyndale is rejecting the way these words have been used to support doctrines he is convinced are entirely unbiblical, and dangerous. He wants instead for the translation to reflect the text itself, not a doctrinal system foreign to it.

In other words, he is making the New Testament refer inwardly to itself, as he instructs his readers to do, and not outwardly to the enormous secondary construction of late-mediaeval practices of the Church: priests and penance and confession and charity. Interpretation, as he explains in the second paragraph of the epilogue [to his 1526 NT], has to be so that ‘all is conformable and agreeing to the faith’ of the New Testament. He cannot possibly have been unaware that those words in particular undercut the entire sacramental structure of the thousand-year Church throughout Europe, Asia and north Africa.

Daniell, David. William Tyndale: A Biography (pp. 148-149).

But while Tyndale went about changing these few words that would pack such weighty punch, he did not see himself as undercutting the sacramental system. Rather, “It was the Greek New Testament that was doing the undercutting.”

Some Fight Against Love

As was to be expected, Tyndale’s return to the Greek text was not well received by all. Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall railed against Tyndale and what he had written. He preached a sermon (no longer extant) reportedly claiming that Tyndale’s new translation had some 2000 errors in it. It would seem that Tyndale’s choice of “love” was among these. Eventually, Tunstall would go so far as to call for Tyndale’s translation to be burned. Yes, he burned the New Testament, to Tyndale’s great shock and dismay. Daniell notes that it has been commonly claimed that Tunstall found fault only in Tyndale’s marginal notes, which, it is claimed, were too bitter. But this cannot be the real reason, for there are no marginal notes in the 1526 NT, (and if the 1525 is meant, it only got through the first 21 chapters of Matthew, and with no bitter notes). The case collapses, and in fact, “Tunstall’s attack can only have been on Tyndale’s rendering of the New Testament text itself. Two thousand errors in a volume of 680 pages gives an average rate of three per page. Some of these would be words to which the most serious offence could be taken by the Church, like ‘congregation’ for ‘church’, ‘love’ for ‘charity’, and ‘repent’ for ‘do penance’” (William Tyndale, pg. 192).

It was not marginal notations which brought hatred of Tyndale. It was the Greek text, now clearly and directly in English. Especially, it was this handful of dangerous words, the change of which could overthrow a millennium of ecclesiastic tradition. Such hotspot words were enough to get a translation burned. They were enough, in fact, to get a translator burned.

Tunstall was not the only one upset about what Tyndale had done. Sir Thomas More (of “Utopia” fame in the history of English works), was aghast at Tyndale’s blatant attack on the established church. Daniell picks up More’s attitude well;

Of course More was offended by the English New Testament. He did not need anyone, thank you very much, and certainly not some stray Englishman living abroad, to tell him that ‘priest’ should be ‘senior’, that ‘church’ should be ‘congregation’ and that ‘charity’ should be ‘love’; that there was no purgatory in Scripture, and that five of the seven sacraments were not sacraments at all. In the whirligig of time and fashion, Tyndale is today only known in some powerful intellectual circles as an annoyance to the blessed Saint Thomas, clinging like a burr to the great man’s coat, as if Tyndale’s life were meaningless without More.

Willlian Tyndale, pg. 252 [edit – should be 262].

In June 1529, More wrote his, A Dialogue Concerning Heresies, (read a PDF here, from which I cite below) no small part of which was to lambast Tyndale for his translation choices, which More was convinced were an intentional attack on the Catholic Church and its doctrines. David Norton explains;

In the earlier work, A Dialogue Concerning Heresies (1529), More instances some false translations of words, refers to the difficulties of translation and responds to the argument against English. Discussing Tyndale’s use of ‘seniors’ for ‘priests’, ‘congregation’ for ‘Church’ and ‘love’ for ‘charity’, he observes that ‘these names in our English tongue neither express the thing that he meant by them, and also there appeareth… that he had a mischievous mind in the change’ (Works, VI: 286).

Norton, David. A History of the English Bible as Literature (Page 22).

More repeatedly charges Tyndale with writing an English New Testament fashioned after Luther’s Protestant theology;

Which whoso calleth ‘the New Testament’ calleth it by a wrong name… except they will call it ‘Tyndale’s Testament,’ or ‘Luther’s Testament.’ For so had Tyndale after Luther’s counsel corrupted and changed it from the good and wholesome doctrine of Christ to the devilish heresies of their own… that it was clean a contrary thing!

More was not wrong. He takes up at several points Tyndale’s choice for “love” instead of “charity,” and what he assumes to be Tyndale’s rationale behind it. He frames the whole of his work as a dialogue between himself (the author) and a fictional character, “the messenger,” which allows him a kind of diatribe of his own making.

Now, where he calleth the Church always the ‘congregation,’ what reason had he therein? For every man well seeth that though the Church be indeed a congregation, yet is not every congregation the Church, but a congregation of Christian people… which congregation of Christian people hath been in England always called and known by the name of the Church; which name what good cause or color could he find to turn into the name of ‘congregation,’ which word is common to a company of Christian men or a company of Turks?

Like wisdom was there in the change of this word ‘charity’ into ‘love.’ For though charity be always love, yet is not, ye wot well, love always charity.

The more pity, by my faith,” quoth your friend, “that ever love was sin! And yet it would not be so much so taken if the world were no more suspicious than they say that good Saint Francis was, which when he saw a young man kiss a girl once in way of good company… knelt down and held up his hands into heaven, highly thanking God that ‘charity’ was ‘not yet gone out of this wretched world.’

More’s imagined opponent claims the change is for the better. More patiently and kindly explains to his absurdly ignorant interlocutor that of course, if the change were for the better, the author would support it. He does not, for it is not “better.” And it is not seldom, which could be forgiven;

If he called charity sometimes by the bare name of ‘love,’ I would not stick thereat. But, now, whereas ‘charity’ signifieth in Englishmen’s ears not every common love, but a good, virtuous, and well-ordered love: he that will studiously flee from that name of good love, and always speak of ‘love’ and always leave out ‘good,’ I would surely say that he meaneth naught.

He goes on to accuse Tyndale of collaborating with Luther. He comes finally to specifically charge Tyndale with changing this word in order to slip in Luther’s doctrine of justification by faith, and remove the implications inherent in the word “charity” for justification by works. He writes, under the heading, Luther’s Heresies, of what he at least sees as the real reason Tyndale has made his change;

But, now, the cause why he changed the name of ‘charity,’ and of the ‘church,’ and of ‘priesthood,’ is no very great difficulty to perceive. For since Luther and his fellows among other their damnable heresies have one that all our salvation standeth in faith alone, and toward our salvation nothing force of good works: therefore it seemeth that he laboreth of purpose to diminish the reverent mind that men bear to charity… and therefore he changeth that name of holy, virtuous affection into the bare name of ‘love,’ common to the virtuous love that man beareth to God… and to the lewd love that is 3.8 between fleck and his make. And for because that Luther utterly denieth the very, catholic church in earth… and saith that the church of Christ is but an unknown congregation of some folk, here two and there three, no man wot where, having ‘the right faith’ (which he calleth only his own new-forged faith): therefore Hutchins in the New Testament cannot abide the name of the ‘church,’ but turneth it into the name of ‘congregation,’ willing that it should seem to Englishmen… either that Christ in the Gospel had never spoken of the Church… or else that the church were but such a congregation as they might have occasion to say that a congregation of some such heretics were the church that God spoke of.

As David Norton explains, “More’s chief concern is with heretical tendencies in the translation. Among these is the choice of certain words through which, with some justification, he sees Tyndale as attacking the teaching and practice of the [Roman] Church” (A History of the English Bible as Literature, pg. 21-22).

Tyndale Fights For Love

When we examine the charge of More that Tyndale is peddling Lutheran ideas, we find that, once again, More is not wrong. Tyndale has indeed been influenced by Luther. He is indeed a Protestant, and is indeed creating a distinctly (perhaps even divisively) Protestant English text. He is convinced that in Luther’s theology alone can Paul be truly heard. As Daniell notes, “At bottom, Tyndale’s offence has been to offer the people Paul in English, and translate four key New Testament words (presbuteros, ekklesia, agape, metanoeo) in their correct Greek meanings (senior, congregation, love, repent) instead of priest, church, charity and do penance” (Willaim Tyndale, pg. 269). Tyndale of course came later to respond to these charges. He wrote his, An Answer to Sir Thomas More’s Dialogue, in 1536, to which More would write yet another massive response, The Confutation Of Tyndale’s Answer. Tyndale briefly defended (in far fewer words than all More’s complaints), among other things, his choice of the word “love” instead of “charity.” Interestingly, he responds to the first part of More’s accusation about the word without dealing with the heart of More’s objection (that Tyndale is a Protestant after Luther’s own heart). Perhaps because the deeper charge was true. In any case, Tyndale’s defense is worth hearing at length. He writes, under the heading, Why he useth love, rather than charity;

He rebuketh me also that I translate this Greek word agape into love, and not rather into charity, so holy and so known a term. Verily, charity is no known English, in that sense which agape requireth. For when we say, ‘Give your alms in the worship of God, and sweet St Charity;’ and when the father teacheth his son to say, ‘Blessing, father, for St Charity;’ what mean they? In good faith they wot not. Moreover, when we say, ‘God help you, I have done my charity for this day,’ do we not take it for alms? and, ‘The man is ever chiding and out of charity;’ and, ‘I beshrew him, saving my charity;’ there we take it for patience. And when I say, ‘A charitable man,’ it is taken for merciful. And though mercifulness be a good love, or rather spring of a good love, yet is not every good love mercifulness. As when a woman loveth her husband godly, or a man his wife or his friend that is in none adversity, it is not always mercifulness. Also we say not, This man hath a great charity to God; but a great love. Wherefore I must have used this general term love in spite of mine heart oftentimes. And agape and caritas were words used among the heathen, ere Christ came; and signified therefore more than a godly love. And we may say well enough, and have heard it spoken, that the Turks be charitable one to another among themselves, and some of them unto the Christians too. Besides all this, agape is common unto all loves.

And when M. More saith, “Every love is not charity;” no more is every apostle Christ’s apostle; nor every angel God’s angel; nor every hope Christian hope; nor every faith, or belief, Christ’s belief; and so by an hundred thousand words: so that if I should always use but a word that were no more general than the word I interpret, I should interpret nothing at all. But the matter itself and the circumstances do declare what love,* what hope, and what faith is spoken of. And, finally, I say not, charity God, or charity your neighbour; but, love God, and love your neighbour; yea, and though we say a man ought to love his neighbour’s wife and his daughter, a christian man doth not understand that he is commanded to defile his neighbour’s wife or his neighbour’s daughter.

William Tyndale, An Answer to Sir Thomas More’s Dialogue, the Supper of the Lord after the True Meaning of John VI. and 1 Cor. XI. and Wm. Tracy’s Testament Expounded, ed. Henry Walter, vol. 3, The Works of William Tyndale (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1850), 20–21.

Charity is one of those words that had become a virtual flashpoint for Catholic/Protestant debate, containing in itself, in some ways, the seeds of the whole Reformation question. S. R. Maveety noted the debate between Luther and More, and More’s charge that Tyndale was “guilty of intentionally mistranslating the Bible for the sake of Lutheran doctrine,” then cites the four examples above (including charity/love), and explains, “It may seem remarkable to us today that these translations helped bring Tyndale to death at the stake, but to More and Tyndale and men of their time the words were more loaded than one might suspect.” Tyndale, for his part, was convinced he was only letting the Greek text speak on its own, and that it was not him opposed to Catholic doctrine, it was the NT itself. This doesn’t mean he is altogether opposed to the word charity. He even uses it once in reference to I Cor. 13, (since he saw that passage in particular as requiring deeds of service to others). But for Tyndale, while love may require action, it can never be reduced to it, or equated with it. Love patently demands affection. It must be felt, and only the gospel can cause it to be so felt, as joyous thanksgiving for the work Christ has already done, not as work that we must do.

One passage at random, among many that could be chosen, makes the point. Tyndale argues at length in The Parable of the Wicked Mammon for the reformed doctrine of justification by faith alone. As part of that argument, he employes the phrase in Luke 7, “Many sins are forgiven her, for she loveth much.” He qualifies, immediately, to avoid any implication of works;

Not that love was cause of forgiveness of sins, but contrariwise the forgiveness of sins caused love; as it followeth, “To whom less was forgiven, that same loveth less.” And afore he commended the judgment of Simon, which answered that he loveth most to whom most was forgiven: and also said, at the last, “Thy faith hath saved thee” (or made thee safe), “go in peace.” We cannot love, except we see some benefit and kindness. As long as we look on the law of God only, where we see but sin and damnation and the wrath of God upon us, yea, where we were damned afore we were born, we cannot love God: no, we cannot but hate him as a tyrant, unrighteous, unjust, and flee from him as did Cain. But when the gospel, that glad tidings, and joyful promises are preached, how that in Christ God loveth us first, forgiveth us, and hath mercy on us; then love we again, and the deeds of our love declare our faith. This is the manner of speaking: as we say, Summer is nigh, for the trees blossom. Now is the blossoming of the trees not the cause that summer draweth nigh; but the drawing nigh of summer is the cause of the blossoms, and the blossoms put us in remembrance that summer is at hand. So Christ here teacheth Simon by the ferventness of love in the outward deeds to see a strong faith within, whence so great love springeth. As the manner is to say, Do your charity; shew your charity; do a deed of charity; shew your mercy; do a deed of mercy; meaning thereby that our deeds declare how we love our neighbours, and how much we have compassion on them at their need. Moreover it is not possible to love, except we see a cause. Except we see in our hearts the love and kindness of God to us-ward in Christ our Lord, it is not possible to love God aright.

William Tyndale, Doctrinal Treatises and Introductions to Different Portions of the Holy Scriptures, Vol. 1, pg. 83–84.

Love must be felt, fervently, and can only come in response to the gospel. Then and only then can loving deeds for others proceed, as the fruit of salvation, and the fruit of grasping and feeling the love of God for us. That, for Tyndale, was the force of agape. It could not be reduced to mere action or good deeds. Far from it. Tyndale is the romantic. Love must be experienced. And that is what the empty, “charity,” can never convey, for it is laden with all the connotations of almsgiving, good deeds, and actions, yet utterly divorced from the heart. Tyndale’s passion was to render the Greek text clearly and directly, without the unbiblical baggage of the medieval Latin church. He would defend these words with his own life, ultimately being tied to a stake and strangled. Then his body would be lit aflame and burned there for his stand.

And though I gave my body even that I burned, and yet had no love, it profiteth nothing. (I Cor. 13:3, Tyndale 1536)