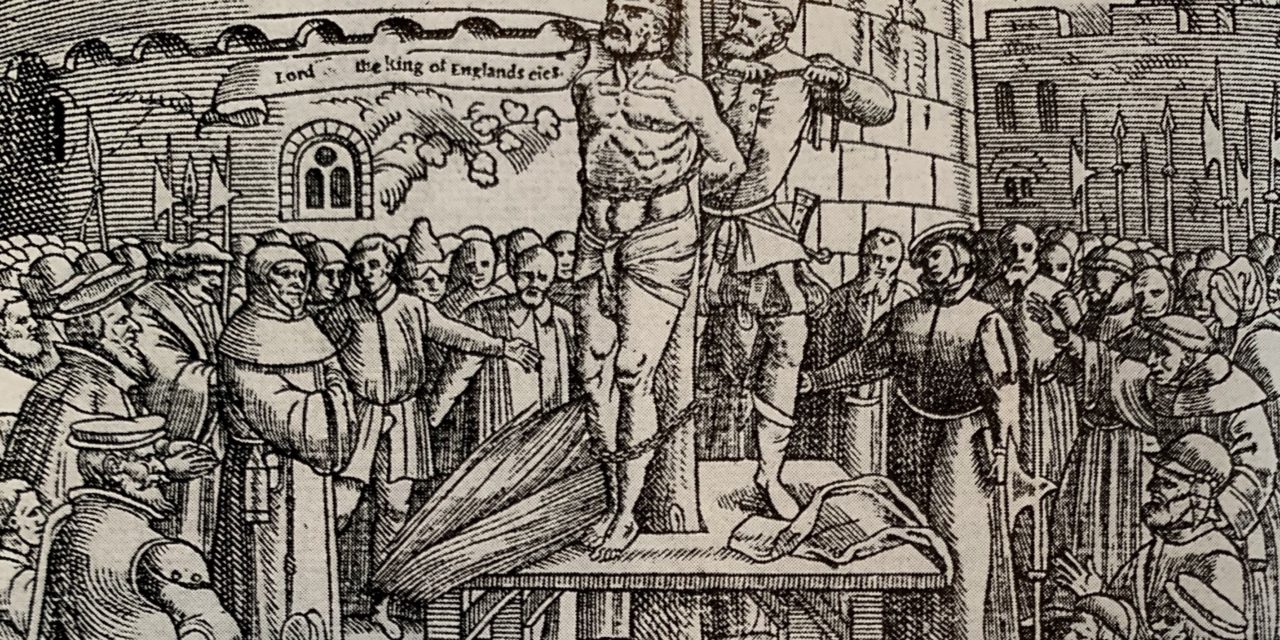

“Lord! open the king of England’s eyes!”

In 16th century Europe, a prayer like this spoken out loud to God was bold no matter who spoke it. Such a prayer borders on both blasphemy and treason – who could dare suggest that the king is blind, or worse yet, that God is not on his side? But the striking prayer captivates us even more as we watch on while it is cried out by a man, on October 6th, 1536, tied to a stake. He is finally strangled with a rope, as though in a last effort to silence his dangerous voice. His body now silent and limp, he is then burned at that same stake.

The man, of course, is William Tyndale (rhymes with kindle). After 18 months in prison, he had been in August officially condemned as a heretic, stripped of his priesthood, and handed over to the authorities for punishment. His crime? Heresy. But hidden behind that charge was his real crime – giving the common English people the Bible in their own tongue, and, to boot, Luther’s Reformation theology along with it.

That’s how the story ends. But how did it begin?

Tyndale And The Birth Of A Dream

We don’t know when he (or his two brothers) was born exactly – sometime between 1492-1495. David Teems notes with exasperation, “We know more about the sound of his last name than we do the year he was born, who his parents were, where he grew up, how old he was when he attended Oxford, and whether or not he attended Cambridge as certain histories imply, or why there seems to have been two family names.”

We do know that in 1508 he entered Magdalen College at Oxford, (some say, at the age of 12), where he took his B.A. on July 4th, 1512, and his M.A. two years later. In 1521, he found himself working in Gloucestershire, serving as a tutor to the children at Little Sodbury, the estate of the wealthy Sir John Walsh. (See his room on the left, image from Christian History Magazine.) Here, at some point, he developed a singular passion that would consume his life. He gave himself more and more to the study of the Greek New Testament of Erasmus. And he became increasingly of the conviction that this was a book – the book – by which God would speak to the common people. John Foxe (of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, properly titled, Acts and Monuments of These Latter and Perilous Days, Touching Matters of the Church, Wherein Are Comprehended and Described the Great Persecutions Horrible Troubles, That Have Bene Wrought and Practiced by the Romish Prelates, Specially in This Realm of England and Scotland, from the Year of Our Lord, a Thousand unto the Time Now Present. Gathered and Collected According to the True Copies Writings Certificatory, or The Acts and Monuments for short) recounts a small story of a conversation during this time that shows us this passion up close, in Tyndale’s own words (spelling and punctuation updated);

And soon after, Master Tyndale happened to be in the company of a learned man. And in coming and disputing with him, drove him to that issue that the learned man said, “We were better be without God’s law, than the Pope’s.” Master Tyndale, hearing that, answered him, “I defy the Pope and all his laws,” and said, “If God spare my life, ere many years, I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost.”

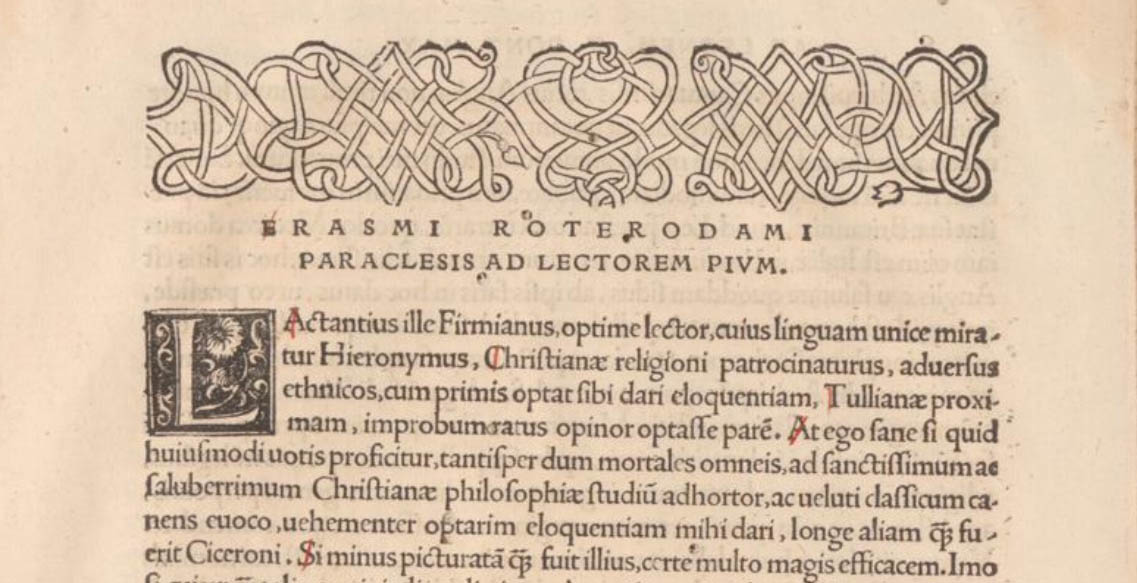

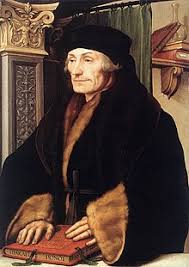

The passion of the Dutch Humanist scholar, Erasmus of Rotterdam, spills out of Tyndale’s mouth. Erasmus had written in his Paraclesis, at the front of his 1516 edition of the Latin/Greek NT,

I disagree entirely with those who do not want divine literature to be translated into the vernacular tongues and read by ordinary people, as if Christ taught such convoluted doctrine that it could be understood only by a handful of theologians, and then with difficulty; or as if the defense of the Christian religion were contingent on this, that it remain unknown. Perhaps it is expedient to conceal the secrets of kings, but Christ desires his mysteries to be known as widely as possible. I would like every woman to read the Gospel, to read the Epistles of Paul. And oh, that these books were translated into every tongue of every land so that not only the Scots and the Irish but Turks and Saracens too could read and get to know them. The first stage, unquestionably, is to get to know them – somehow or other. Granted that many people would laugh; yet some would be won over. How I wish that the farmer at his plough would chant some passage from these books, that the weaver at his shuttles would sing something from them; that the traveller would relieve the tedium of his journey with stories of this kind; that all the discussions of all Christians would start from these books…

—Erasmus of Rotterdam (CWE 41)

Clearly Tyndale has not only lived in the Greek biblical text of Erasmus – he has been stirred by its prefatory material as well. Erasmus was a man of words. What he expressed as wish – perhaps even prayer – Tyndale, a man of action if nothing else, will make a life goal.

The Bible in England had long been somewhat obscured in the Latin of the Vulgate. This doesn’t mean it wasn’t accessible at all. The people had numerous ways of imbibing some parts of Scripture in public liturgy. But it did mean that setting down to read it for one’s self, in one’s own tongue, was not, for most common people, even an option. In much (most?) of the world at the time, it would not have been such a problem to give the common people a Bible in their own language. But in England, in just this same window of time, it happened to still be illegal.

Perhaps it is expedient to conceal the secrets of kings, but Christ desires his mysteries to be known as widely as possible.

—Erasmus of Rotterdam

The Constitutions of Oxford from 1408 were still in force. In the wake of the work of that arch-heretic John Wycliffe, Archbishop Thomas Arundel had declared that, “The translation of the text of Holy Scripture out of one tongue into another is a dangerous thing,” and decreed against the Lollards that,

…Therefore we enact and ordain that no one henceforth do by his own authority translate any text of Holy Scripture into the English tongue or any other by way of book, pamphlet, or treatise. Nor let any such book, pamphlet, or treatise now lately composed in the time of John Wicklif aforesaid, or since, or hereafter to be composed, be read in whole or in part, in public or in private, under pain of the greater excommunication….Let him that do contrary be punished in the same manner as a supporter of heresy and error.

However dangerous, his passion to take the original Greek and Hebrew texts and put them into English consumed him. He soon realized that this was no easy task. He initially attempted to follow legal channels to produce an authorized English Bible. But such was not to be allowed. As Tyndale himself noted in the later preface to his Pentateuch, he, “understood at the last not only that there was no room in my lord of London’s palace to translate the new Testament, but also that there was no place to do it in all England, as experience doth now openly declare.” The powers that be in England had no wish for the people to read the Bible in their own tongue. Such a dream was dangerous.

Tyndale was equipped as few could be to accomplish his dream. He had learned Greek at Oxford, then Hebrew, and became eventually what we could call a multi-linguistic genius. These were not aimless pursuits – they were servants to his grander cause. Tyndale Scholar and biographer David Daniell notes;

William Tyndale was a most remarkable scholar and linguist, whose eight languages included skill in Greek and Hebrew far above the ordinary for an Englishman of the time—indeed, Hebrew was virtually unknown in England. His unsurpassed ability was to work as a translator with the sounds and rhythms as well as the senses of English, to create unforgettable words, phrases, paragraphs and chapters, and to do so in a way that, again unusually for the time, is still, even today, direct and living: newspaper headlines still quote Tyndale, though unknowingly, and he has reached more people than even Shakespeare. At the centre of it all for him was his root in the deepest heart of New Testament theology, a faith of the sort that can, and did, move mountains.

William Tyndale As Pioneer Translator

But his was a road that was not only hard, it was also new; he was blazing a new path. Snippets of English Scripture had existed, and of course, Wycliffe’s versions existed in English. But Wycliffe and the Lollards had translated from Latin into English. Caught up in the age of the Renaissance, Tyndale’s passion was to give the original Greek and Hebrew in English. Here, as he would note, he, “had no man to counterfeit, neither was helped with English of any that had interpreted the same or such like thing in the scripture beforetime.” Tyndale was fashioning a new translation, and it was not a road “less traveled” so much as bush through which a trail needed to be cut.

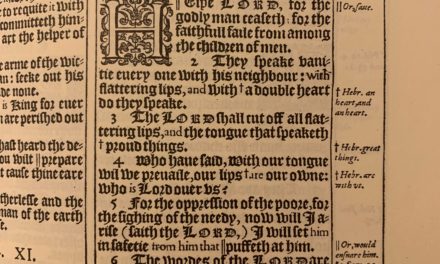

The 1525 Cologne Fragment

In 1525, from the press in Cologne, he begun to print his NT. He reportedly got as far as part of Mark. But he was interrupted, and unable to complete the work, as the Cologne authorities came to arrest him and confiscate his work. All that remains from this work today is Matthew 1-22 and his prologue, in a single fragment. It is the first time in an extant work that we can hear his voice in print. Daniell notes that most of this text of Matt. 1-22 came unchanged into his later edition But he urges us not to miss the significance of something much more important that is happening;

…the English into which Tyndale is translating has a special quality for the time, being the simple, direct form of the spoken language, with a dignity and harmony that make it perfect for what it is doing. Tyndale is in the process of giving us a Bible language. Luther is often praised for having given, in the ‘September Bible’, a language to the emerging German nation. In his Bible translations, Tyndale’s conscious use of everyday words, without inversions, in a neutral word-order, and his wonderful ear for rhythmic patterns, gave to English not only a Bible language, but a new prose.

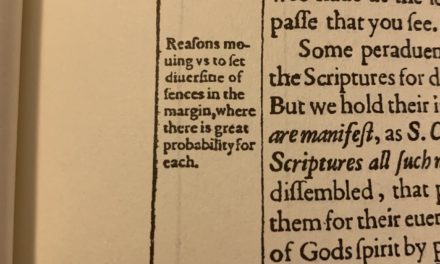

Marginal Notes

While the later printed full NT has no marginal notes, this early fragment from Cologne has some 90 of them just in the extant 22 chapters of Matthew. Had Tyndale continued on with this original plan in his full NT later, we can only imagine the wealth of information we might have from his notes.

The 1526 NT

In 1526, at Worms, Tyndale finally completed printing of his entire NT. Here, Daniell notes, for the first time, was the original Greek NT in English;

We must not lose sight of the extraordinary quality of that first printed New Testament in English, as it was welcomed and read in London and southern and eastern England. Here was suddenly the complete New Testament, all twenty-seven books, the four Gospels, the Acts, the twenty-one Epistles and Revelation, in very portable form, clearly printed. Here was the original Greek, in English. The bare text itself was complete, and without an iota of allegorising commentary. Everything that had been originally written was here, to be read freely without addition or subtraction. The only constraints were the implicit command to read it, and in reading to relate one text to another, even one book to another, so that the high theology of Paul in the Epistles could be understood in relation to the words and work of Jesus in the Gospels.

Yet Tyndale reads like a modern text;

What still strikes a late-twentieth-century reader is how modern it is….both vocabulary and syntax are not only recognisable today, they still belong to today’s language….Tyndale goes for clear, everyday, spoken, English. Because it was largely the current language of his day, it remains largely a current language of ours. He is not out to make antiquarian effects, as the Authorised Version did, for partly political reasons. The result is that Tyndale usually feels more modern than the Authorised Version, though that revision was made nearly a century later.

The King James Bible of 1611 would tend to Latinize the English text, making it more elegant, but also more ambiguous, less direct, and less clear. Tyndale, by contrast, was direct, forceful, and above all, clear. This was no accident – it was by theological conviction. Daniell explains, “Central to Tyndale’s insistence on the need for the Scriptures in English was his grasp that Paul had to be understood in relation to each reader’s salvation, and he needed there, above all, to be clear.”

As the last sheets came off the press, Tyndale’s primary dream was realized. The Bible (the NT at least) had come finally into the common tongue.

God had learned to speak English.

As Daniell concludes, “The boy that driveth the plough had got his Scripture.”

Tyndale’s English

Daniell notes that, “With this volume, Tyndale gave us a Bible language.” David Teems explains that, “Today, in our common English, we speak Tyndale more than we do Shakespeare. And the King James Bible with its high step and its lovely old voice gets the applause that rightfully belongs to William Tyndale.” Teems goes on to point out that;

If you have ever bid someone a warm Godspeed, you have William Tyndale to thank for the blessing. And network is not a word you might have expected to hear in 1530. Tyndale set these two words adrift into the English language almost five hundred years ago, and with them words like Jehovah, thanksgiving, passover, intercession, holy place, atonement, Mercy seat, judgement seat, chasten, impure, longed, apostleship, brotherly, sorcerer, whoremonger, viper, and godless. This is just a start. An impressive start, certainly, and there are literally hundreds more.

A long list of expressions come into English as virgin speech through Tyndale. Teems lists just a small sample of examples (a much longer list of words, also incomplete, is included in an appendix to his work);

- Behold the lamb of God

- I am the way, the truth, and the life

- In my father’s house are many mansions

- For thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory

- Seek, and ye shall find

- With God all things are possible

- In him we live, move, and have our being

- Be not weary in well doing

- Looking unto Jesus, the author and finisher of our faith

- Behold, I stand at the door and knock

- Let not your hearts be troubled

- The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak

- For my yoke is easy and my burden is light

- Fight the good fight

Teems asks us to picture what such words must have meant to those who first heard them;

Imagine hearing these words for the first time, especially after being denied this most primary exchange for centuries. God is no longer hoarded or kept at a distance. He is flush, lucent. And he sounds like you sound. He uses your words, your patterns and rhythms. There is no longer a wall, or a divide, at least not by way of speech. The generosity alone is overwhelming.

—David Teems, Tyndale: The Man Who Gave God An English Voice

Tyndale in his text urges his reader to listen closely – God is speaking in these pages. Hear him with no mixture. Hear him speak your own language. In his “W.T. To The Reader,” at the back of the work, he writes, “Give diligence, reader, I exhort thee, that thou come with a pure mind, and, as the scripture saith, with a single eye, unto the words of health and of eternal life; by the which, if we repent and believe them, we are born anew, created afresh, and enjoy the fruits of the blood of Christ….”

He reminds the reader that should they find fault, they should keep in mind that he has interpreted the text, according to his gifts, as far as God gave him. His conscience is clear. And if any “rudeness” be found in the text, “consider how that I had no man to counterfeit, neither was helped with English of any that had interpreted the same or such like thing in the scripture beforetime.” Pioneers always make some missteps. Tyndale’s text is not the final word – no English translation ever could be, from his point of view. Rather, the reader should, “Count it as a thing not having his full shape, but as it were born before his time, even as a thing begun rather than finished.” Translation is, for Tyndale, always somewhat provisional. It can always be made better.

A Brief Introduction to the Life and Ministry of William Tyndale from Crossway on Vimeo.

Daniell notes in the introduction to his modern-spelling edition of the 1534 NT of Tyndale, “Astonishment is still voiced that the dignitaries who prepared the 1611 Authorized Version for King James spoke so often with one voice – apparently miraculously. Of course they did: the voice (never acknowledged by them) was Tyndale’s. Much of the New Testament in the 1611 Authorized Version (King James Version) came directly from Tyndale…” One more precise study showed that the NT of the KJV is 83.7% the work of William Tyndale, retweeted, without direct credit given. Watch an illuminating interview with Daniell about Tyndale here.

Tyndale will continue to work, and continue to write. In our next post, we will examine his various non-biblical writings, his work on the OT text, and his work as a Bible “reviser” improving his text.

Tyndale’s story is not over yet.

Comments