Psalm 12:6-7 has become a major proof-text for the doctrine of verbal plenary preservation. One would be hard-pressed to find many documents presenting the “TR and MT = The Divine Originals” position (or any other form of KJV – only position) that does not refer to it as a major support for the position. It is mentioned in many doctrinal statements on the issue, and it is referred to often in popular preaching.

I suspect that if most who hold a “TR = Divine Originals” position were pressed to give Scriptural support for why they believe they should only use and endorse the KJV, this is the verse they would most immediately quote. We will deal with the doctrine of preservation as a whole and the steps that must be taken to get from it to a KJV position after concluding multiple essays which examine each purportedly relevant passage in detail, but in this essay we must ask exactly what contribution this text in particular makes to the doctrine of preservation. What does it say about preservation? Let us examine it briefly.

To the chief Musician upon Sheminith, A Psalm of David.

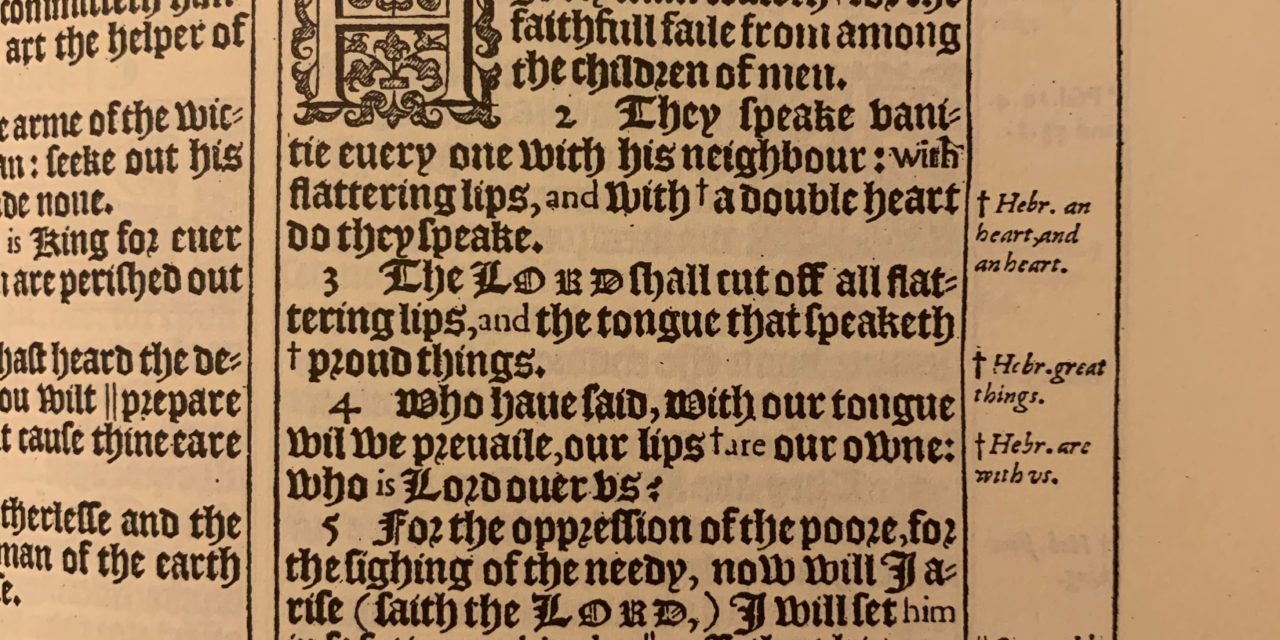

Help, LORD; for the godly man ceaseth; for the faithful fail from among the children of men. They speak vanity every one with his neighbour: with flattering lips and with a double heart do they speak. The LORD shall cut off all flattering lips, and the tongue that speaketh proud things: Who have said, With our tongue will we prevail; our lips are our own: who is lord over us?

For the oppression of the poor, for the sighing of the needy, now will I arise, saith the LORD; I will set him in safety from him that puffeth at him.

The words of the LORD are pure words: as silver tried in a furnace of earth, purified seven times. Thou shalt keep them, O LORD, thou shalt preserve them from this generation for ever. The wicked walk on every side, when the vilest men are exalted.

Author

If we accept the superscription, which will not be argued for here (they are part of the canonical text of the Hebrew Bible, and thus numbered as “verse 1” in most Hebrew texts, See WBC, Craigie, pg. 31), the author is David.

Occasion

While the specific occasion in David’s life that brought the psalm forth is difficult to pinpoint, it seems clear from vs. 1 that godly and faithful men who are truth-tellers have become more and more scarce. David is surrounded by those who speak vanity and flattery from a double-heart (vs. 2). These lies and liars have become oppressive to the poor (vs. 4, 5). Allen Ross notes, “Whatever the exact situation, the psalm indicates that there was a smaller number of people who were faithful to God – and they longed for deliverance from the corruption of the time. In this the psalm is timeless: the world today is still filled with liars and false flatterers so that the righteous do not know who or what they can trust. The psalm affirms that only God’s word can be trusted.” [1]

Purpose

The purpose of the psalm is to strengthen the confidence of the people that God will deliver them from oppressive deception. The “FCF” is thus the tendency to feel hopeless in the midst of the overwhelming and oppressive deception of the wicked. The Grace of the Passage (or the theology and message of the text) is the promise of God to deliver the poor and the needy from that affliction.

Recipients

The superscription shows that this was one of about 50 psalms composed for “The Chief Musician.” This collection of songs became a sort of hymnbook that the choirmaster would use in the congregational worship of the people. Thus, the general audience is worshiping Israel during the Davidic period, as they would gather together for worship and experience this psalm.

Structure

There is general agreement on the basic structure of the psalm, although some commentators introduce minor variations. Longman notes, “The Structure is a movement from prayer (vs. 1-4), to promise (vs. 5) to a renewed assessment of the present world (vs. 6-8).” [2] He lays the structure out in chiastic format as follows; [3]

A Prayer for deliverance (vs. 1-4)

B Promise of the Lord (vs. 5)

B’ Reflection on God’s Promise (vs. 6)

A’ Prayer for Deliverance (vs. 7-8)

Message

Verses 1-4 – The Psalmist Petitions God for Help

“Help, LORD; for the godly man ceaseth; for the faithful fail from among the children of men. They speak vanity every one with his neighbour: with flattering lips and with a double heart do they speak. The LORD shall cut off all flattering lips, and the tongue that speaketh proud things: Who have said, With our tongue will we prevail; our lips are our own: who is lord over us?”

In verses 1-4, David complains that the godly and faithful (truth-tellers) have all but perished from the land. Deceit is rampant, and has begun to oppress the poor. Pride, flattery, and deception are the name of the game now. They speak from a “double heart” (meaning they think one thing, but say another.) They are so arrogant in their speech, that they have asserted that no one can stop them.

Verse 5 – God Promises to Protect those Oppressed by Deception

“For the oppression of the poor, for the sighing of the needy, now will I arise, saith the LORD; I will set him in safety from him that puffeth at him.”

In verse 5, David presents the promise of God that assures the people that they will be protected in their affliction by deceit. When surrounded by deceit that oppresses the poor, David assures the people that God will arise to protect them. The intention of the whole psalm is to assure them of this promise. The means by which David does this is to showcase the promise itself, and then build confidence in God’s declaration. (God said he would protect, and He always does what He says.) The promise in verse five “I will arise…I will set him in safety” is thus the central declaration of the Psalm. Ross summarizes Hebrew scholarship when he says, “All commentators agree that this oracle is the focal point of the psalm.” [4] It is likely that this oracle would have been spoken by a priest or prophet in the midst of the singing of the psalm. [5] That is, the singing would be interrupted by a priest or prophet who would stand and echo the divine promise found in verse 5. This sort of “prophetic oracular reading” of a particular declaration of God was common in the psalms of Israelite worship, as in Psalm 46:10, where the oracle breaks in with the assurance of God. The same can be seen in Psalm 60, 81, and 95. Delitzsch notes of this central declaration, “The Psalm is a ring and this central oracle is its jewel.” [6]

Verses 6-8 – The Psalmist Praises the Purity of God’s Promise

“The words of the LORD are pure words: as silver tried in a furnace of earth, purified seven times. Thou shalt keep them, O LORD, thou shalt preserve them from this generation for ever. The wicked walk on every side, when the vilest men are exalted.”

In verses 6-8, the psalmist reinforces the trustworthiness of the promise made in verse five by explaining that when God says He will do something, He does it. No questions asked, no doubts to be had. Like silver that has been purified through a metallurgical process, there is no impurity in God’s promises. If this is the character of God’s speech, then they can rest confident in the promise made to them that God will arise to set in safety the afflicted. David ends by noting that this does not mean that their troubles will disappear. On the contrary, wicked men will continue to be all around, but God will preserve them in the midst of that wickedness. Longman sums it up, noting, “Regardless of the circumstances of life, God’s children are assured of the special protection of their heavenly Father from the evil of the world in which they live. The wicked may turn the world upside down, but God will guard his own… The Lord will ‘keep safe’ and ‘protect’ his children as promised.” [7]

Impact / Genre

Because the superscription makes clear that this psalm would have been a part of a collection sung communally during public worship, we can identify it as a community lament. We must trace how this would have played out in their worship in order to appreciate the genre. One can only imagine the powerful impact that would have been had upon Israel through this text. Imagine them singing the first four verses to be allowed to express their doubts and despair of truth in the midst of oppression. The laments are designed to let Israel emotionally identify with and express the feelings they have that mirror the psalmist’s. They thus first address God Himself with their petition for help. As they sing the first four verses, they give voice to their deepest feelings of despair at the apparent disappearance of truth and the godly in the land. Then, in the oracle of verse five, they move from speaking to God, to hearing from God. When the priest or prophet interrupts the singing to read the oracle that contains God’s promise, they hear powerfully the Voice of God to them in the midst of their despair. This would no doubt have been an experience to remember.

This voice from heaven changes the entire tone of the meeting. No longer is there despair and hopelessness in a minor key; now there is praise, rejoicing, and excitement. What is the cause of rejoicing? God has made a promise to protect his people, and so they sing praises to the trustworthiness of God’s promises. The people begin to sing again, no longer with despair, but rather with excitement. The choral arrangement of praise in vs. 6-8 is designed to enforce the idea that what God has promised He will preform. This emotional shift would surely have implanted upon their hearts the confidence that God would deliver those oppressed by deception. Verse eight caps the psalm by explaining that while God had promised to protect his people in the midst of lies and liars, He does not promise that He will at this time remove them from the all wicked men. The CIT of the Psalm is something like “When deception is oppressive, God’s promise of protection is sure” or “When God’s people are oppressed by those they can’t trust, the God who never lies will keep His promise to preserve them.” Briggs, in a major exegetical treatment of the psalm, notes that, “Psalm 12 is a prayer, in which the congregation implores Yahweh to save them, for that faithful vanish away and liars prevail (v. 2-3); and to cut off liars (v. 4-5). Yahweh himself says that He will arise, and set the afflicted in safety (v. 6-7b). The congregation finally expresses confidence that Yahweh will preserve them from the wicked round about (v. 8-9).” [8]

Verse 6-7 in More Detail

The Words of the LORD

The word “words” here has occasionally been misunderstood. It is not a reference to “individual words” but rather to the “promises” that God makes. It refers especially to the promises of God (which is its referent in this text, where the direct referent is clearly to the promise of verse 5.) Note the BDB definition. While the verbal form can mean, “To say, say in the heart, promise, or command,” The noun form here (used in its much more rare feminine form) means, “Utterance, speech, word.” BDB notes that it especially means, “Utterance, speech; especially saying(s), or word(s) of Yahweh (command & promise).” [9] The KJV often translates it as “speech.” Note that when it is found in the singular, [10] it is never a reference to an individual “word” (as a unit that makes up a part of a phrase), which might give it a verbal referent, but rather always refers to the whole speech or oracle. Thus, in the plural it is likely to mean multiple speeches or oracles, not multiple “words.” [11] A promise of verbal preservation isn’t likely to find much support is such a use.

However, it is also unlikely that one could find the canon as a whole being referred to here. When the psalmist describes the “words of the Lord” he is almost certainly not making an abstract statement about the canon as a whole. This concept would have been utterly foreign to his original readers / hearers. Some may have taken the phrase that way, but in the context, he is making a statement about the general character of God’s speech. This is why he uses the plural of this particular word; to say that, whenever God speaks, He will do what He says. He invokes this affirmation of the reliability of God’s speech for the purpose of referring to the promise of verse five that He “will arise” and “set the godly in safety.” In the context of the whole psalm, this is the only “word of the Lord” which he intends to describe. It is the only “word of the Lord” that the hearers are concerned about. It is the only “word of the Lord” found anywhere in the context. However, even if he were referring to the whole canon in verse six, the point of verse seven has still been sorely missed. I think the phrase here in its context clearly refers to the oracular promise of verse five, but even if it did refer to the whole canon, that still doesn’t affect the interpretation of verse seven. So what does verse seven teach?

“Thou shalt keep them, O LORD, thou shalt preserve them from this generation for ever.”

The thrust of the Psalm as a whole is repeated in verse seven, where David reiterates the promise from verse five that God will protect His people. But now it is repeated as the confident declaration of a people emboldened by the promise of God. It is almost unthinkable in the context of the psalm as a whole that the verse could mean anything else. The text simply does not say, “God will protect his words.” There are elements of the verse that are disputed (especially the rendering of the last line “from this generation forever”) among commentators, but the idea of the pronoun “them” referring to the “words” of verse six is not even on the table for discussion among commentators. While there may be some out there, I’ve yet to read a commentary which even mentioned that as a possible option.[12] And realize that it is the job of a good critical commentary to examine every possible interpretation of the text. The referent of the pronoun is unspecified in the KJV. The translators simply did not write “thou shalt preserve thy words” and the Hebrew text simply does not say that. At best, one can suggest that the ambiguous English could perhaps be understood that way, though it is certainly not demanded by the English grammar, and is an almost impossible meaning of the Hebrew grammar, and is a poor fit with the context of the psalm as a whole, and especially of verses 6-7, which seek to reiterate and affirm the promise of verse 5. Some who were simply looking to support the theology they already held accidentally read that meaning into the text. The clear antecedent, even in English, is the poor and needy of verse five, and by extension the godly man and faithful men of verse one.

The words for “keep” and “preserve” both carry the idea that God will guard or protect the godly man.[13] Ross notes of the first word, “This idea of ‘protect’ (‘keep’ or ‘guard’) is used for the Lord’s protection of his people.”[14] David is saying that God will preserve his faithful people in the midst of the their affliction. Like the Cherubim guarding the tree of life (Gen. 3:24), God will guard His people in the midst of their affliction.

“Thou shalt keep them”

The Object of the verb “keep” in the first line is the 3rd person masculine plural suffix “ם” meaning “them.” Yet there is not a perfectly accurate way translate this into English, since we can’t retain gender in the plural in English. There is no English form “hims.” [15] In English, in a plural pronoun, we lose all sense of gender (In other words, “them” doesn’t specify male, female, or neuter.) Yet the Hebrew word for “words” (אִֽמֲר֣וֹת” ”) in verse 6 is in the feminine gender. While a masculine pronoun can at times be used to refer to a feminine antecedent, [16] it is less likely that the masculine pronoun refers to a feminine antecedent than that it refers to a similar masculine one, especially in the context of the psalm as a whole. It would be a case of pronoun – antecedent disagreement in gender. It is rather more likely that the “godly man” and the “faithful” (both masculine) of verse one and the “poor” and “needy” and “him” of verse five (both masculine) are the object of the promise. The most natural reading of the Hebrew text when coming to a masculine pronoun would be to look for an antecedent that is also masculine. Since the godly man and faithful have already been the context of the entire Psalm, no one reading the Hebrew would see anything else.

Further, pronouns in Hebrew are much more often personal than inanimate. That is, it is much more likely in terms of grammatical precedent that the antecedent is the personal “poor and needy” than the inanimate “words.” Waltke notes, “One special feature of the Hebrew personal pronouns is the extent to which they refer to persons rather than objects, or, more strictly, to animates rather than inanimates.” [17] This is clearly a promise that God will preserve his people, not a promise that He will preserve his words. Only in English translation is any ambiguity introduced.

“thou shalt preserve them”

The promise in the second line is even more explicit. “Thou shalt preserve them.” In this case the object of the verb is the 3rd person masculine singular suffix “וּ ” meaning “him,” not the plural “them.” [18] Thus the technically more “formally equivalent” translation of the MT is actually “Thou shalt preserve him.” In fact, this is precisely how the text was rendered in several English translations prior to the KJV. [19] The Geneva Bible had,

“Thou wilt keepe them, O Lord: thou wilt preserve him from this generation for ever.”

The Great Bible had,

“Thou shalt kepe them (O Lorde) thou shalt preserve hym from thys generacyon for ever.”

The Bishop’s Bible clearly understood the reference to be to the godly (and used a less literal translation in the first line which makes this clear), but had taken the pronominal suffix to be a collective reference to every one of the “hims” in view, and thus read,

“[Wherfore] thou wylt kepe the godly, O God: thou wylt preserue euery one of them from this generation for euer.”

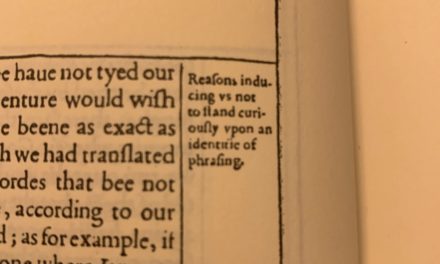

The KJV is simply a revision of the Bishop’s Bible of 1602, [20] and they have retained this understanding, interpretation, and translation of the text. This is clearly the interpretation they mean for their translation to convey, but now putting in a marginal note the explanation that had been part of the Bishop’s Bible text, as we will see below.

This is clearly the promise of verse five reiterated that God will “set him in safety from him that puffeth at him.” It would be a case of pronoun – antecedent disagreement in both number and gender to take the singular pronoun here (KJV “them”) as referring to the plural noun, “words” of verse 6. While one or other of these is possible in certain special usages of the plural, [21] none of these special cases is unambiguously found here. It is thus not grammatically likely that the “thou shalt preserve them” of verse seven is a reference to the “words” of verse six. However, because the two lines of verse 6 are a parallelism, with the first one using the plural masculine (“Hims”) and the second using the singular (him), it is likely that what is intended by “him” is the distributive sense meaning “every one of the ‘hims’ of the previously mentioned group.” REBC notes that the alternation between plural and singular of the Hebrew text is an intentional device throughout the psalm to refer to the people, and is simply repeating the same alternation that occurs in verse one and verse five in reference to the people. “The suffixes on the verbs refer to the people first as ‘them’ and then individually as ‘him,’ just as the singular and plural alternated in vs. 1 and 5.” [22] In other words, in verse 1, notice how the psalmist employs both the singular and plural to refer to the people. The “godly man” is singular, while the “faithful” is plural. He uses the same device in verse 5, switching between the singular and plural and using both to refer to the people. Thus, “poor” and “needy” are both plural, but the object of the verb “set” (the pronominal suffix at the end of the preposition) is singular. This is why the KJV translates there, that God will set him in safety from him that, “puffeth at him,” which is the singular. This switch back-and-forth of the singular and plural is employed only of the people in the psalm. The “Words” of the Lord are referred to only in the plural throughout the psalm. They cannot therefore likely be the referent of the promise of preservation in verse seven, which employs the same singular-plural switch used only of the people.

The KJV translators themselves noted the same phenomenon in the margin of their translation, noting that while they rendered the text “them,” the Hebrew is more literally actually “him.” [23] They explain that it is likely that the distributive sense is in view, noting in the margin,

“Heb. Him, i.e., every one of them.”

(See a copy of the text of the 1611 KJV here, or see the cover photo). They have agreed with the translation of their base text (the Bishop’s 1602) but moved some of the expanded explanation to a marginal note, in the interest of being more literal in translation than the Bishop’s Bible was.

Understand what has taken place here with these two lines. The translators had to either choose, “them” and so maintain the number of the original, but lose the gender, or choose “him” and maintain the gender of the original but lose the number. The meaning in both cases is a plural group of multiple “hims,” employing first the plural then the singular in keeping with the psalmist’s pattern. But there is no form “hims” in English, so every translator must lose something of the original text in translating it into English. The point to note here though is that they clearly understood the referent of the singular suffix as being back to the alternating singular and plural in verses one and five, being a reference to the people. This is surely self-evident to anyone reading the passage in its context, and abundantly evident to anyone who reads the original translators notes (and even more so when they realize the origin of this particular note in the Bishop’s base text). If we had only continued to print these notes, and listened to the KJV translators themselves, so much bad interpretation could have been avoided. Maintaining today that the phrase is a promise to preserve God’s words in the KJV is to utterly disagree with what the translators themselves intended to convey, which, in a text now being adduced as support for their infallibility, seems odd at best.

Maintaining today that the phrase is a promise to preserve God’s words in the KJV is to utterly disagree with what the KJV translators themselves intended to convey, which, in a text now being adduced as support for their infallibility, seems odd at best.

Delitzsch notes the same connection and referent of the pronouns, stating, “The suffix em in Psalm 12:8 [the “them” of our vs. 7] refers to the miserable and poor; the suffix ennu in Psalm 12:8 [the “them” of our verse 7, rendered, “Him” in the KJV margin] (him, not: us [24], which would be pointed תצרנוּ, and more especially since it is not preceded by תשׁמרנוּ) refers back to the man who yearns for deliverance mentioned in the divine utterance of verse 6 [our vs. 5].” [25] Is this an invention of contemporary commentators? Not likely. While there is little in early church writings that refer to this psalm, [26] none of these references would support taking the promise as referring to “words” instead of to “people.” At a later time, Spurgeon apparently took the reference of both verbs in verse 7 to be to God’s people, noting, “The hero is… preserved for ever from the generation which stigmatized him.” [27]

“from this generation for ever”

The word for “generation” here can refer to “a period, age, or generation,” “men living at a particular time” or “a class of men.” [28] It seems most likely that the word is being used in its 3rd sense here. [29] The particular class of men (with stress on the character of men, rather than the time in which they live) being referred to is clear in the context – it is the arrogant liars of verses 1-4. Thus we should not read the entire phrase “from this generation for ever” as a statement of chronological duration. Rather, “from this generation” designates what it is precisely that the psalmist is now confidant God will save his people from. This is clear from the reference to “for ever” meaning “everlastingness, i.e. long duration,”[30] which by itself introduces the eternal time-frame. Thus, David is confident that God will protect his people. What will he protect them from? Clearly, it is this “generation” or this kind of ungodly men. How long will he do this?” Forever.

In summary, the passage in its context is clearly a promise that God will preserve his people, not His words. This is clear from the literary context of the passage as a whole, from the historical context that stands behind it, from the grammar of the Hebrew text itself, and even from the marginal notes of the KJV translators, making clear what they intended by the English of their translation.

Relation to Preservation

Verses 6-7 is the most common (and most explicit) text used to present the doctrine of verbal plenary preservation in the form which suggests that the TR is the pure Word of God and other texts are not. This presentation has been made over and over again. Yet when the psalm as a whole is examined, there is simply no real exegetical basis for suggesting that it teaches this view. Since it is a basic axiom of biblical exegesis that the Word of God can never mean to us what it could not have meant to its original readers, any exposition of the psalm in its context would nullify that understanding of these verses. A survey of biblical commentators both past and present reveals that a reference to preservation has never been a legitimate interpretation of the text. It is not just that when they list the options for the meaning of the verses they list it as the least likely interpretation – I mean they don’t typically refer to it at all as even a possibility because it is not a historically held or exegetically discoverable interpretation.

Consider the historical context behind the passage. Good exegesis always works with the understanding that the content of a passage is a response to its historical context. There is always something going on in the lives of the readers that necessitates the theology of the text, and the message of the text is always God’s loving response to the recipients’ need. In fact, the only way to ever really test our exegesis is to show how our interpretation of the content of the text works as a response to the historical context that occasioned it. But in what conceivable way could the original audience have been wrestling with whether or not the words of the canon were preserved for eternity? The written canon is not in view at all in the psalm. What historical figure could stand behind the text trying to convince them that God’s word had not been preserved? Or that because of textual doubts and uncertainties there was doubt about whether or not they actually had the words of the Lord? These are exclusively modern concerns that we have read back into the text. There is simply no conceivable scenario that fits the historical situation that would explain a reference to preservation as the original meaning of the text. Rather, the Israelites were faced with the rather pressing issue of whether or not God would keep his present promise to them in the midst of their troubles. They were concerned about the pressing concern that the godly seem to have almost ceased, as the psalmist cries in the first verse. God promised to preserve these godly men in verse 5. The FCF facing the Israelites was not whether or not copyist would later make scribal errors when they copied this text – it was weather or not God would keep His promise to preserve His people. This is what verses 6-7 addresses. The issue of the text is clearly one of fulfillment, not preservation.

But what if it didn’t? While the meaning seems clear in Hebrew, in the English translation there is some ambiguity, so if we want to, we can land on the side of a “preservation” interpretation, can’t we? I won’t argue if you do (though I find little exegetical basis for such an interpretation). But think what that ambiguity means. Ambiguity caused by the English translation should at best be allowed to suggest a particular interpretation as possible, not to demand it. Certainly doctrinal formulations shouldn’t be based on an ambiguity, which might possibly be an assertion of the verbal preservation of Scripture. This is all the more so when one is talking about doctrines that have had such a historical tendency to cause division and separation from so many other godly Christians. When the Bible speaks clearly and unambiguously about issues, we should stand with it, whomever that offends. But to take a debated and extremely unlikely interpretation of a passage (that has at best an ambiguous possibility of being interpreted as referring to verbal preservation), as the primary text for such a divisive doctrine may in fact move us far outside of the authority of Scripture. The more divisive a doctrine is, the more well founded it should be in Scripture. It shouldn’t be so that an examination of the most commonly purported foundational proof text for such a doctrine proves at best to be based on what is only a possible interpretation of that text.

But consider further, what if the passage was a clear assertion of the verbal preservation of Scripture? Would that then settle the text and translation issue? Not in the slightest. There is still nothing in the text that would say anything about how that preservation would work. Even if the passage were a clear and undeniable promise of verbal preservation, it would still lend no support to either side of the text and translation argument. When someone on one side says “I think all of God’s words are preserved in the whole of the manuscript tradition, and we should do textual criticism of the manuscripts to know which words are His,” and someone on the other side says, “I think all of God’s word must be preserved in a single text, together, in one place,” the text itself would lend no unique support to either position. It could just as easily support either view. And that is if it did directly teach verbal preservation. This essay has suggested that it most likely does not. Add to this the fact that if it did promise the continuing verbal preservation of the Hebrew text, this would disqualify the KJV from being the text referred to. As the further essay below will show, the KJV is not a “preserved” text. It is a recreated text that did not exist in that form until 1611. And in fact, as this passage would be a direct reference to the OT text, it should be noted, as we explain below, that the original language text behind the KJV OT, being similar to the Bomberg 1524 text, but with occasional intrusion from Kere readings, and occasional emendation from the LXX, the Latin Vulgate, the Aramaic Targums, has never existed in print. So if God were making such a promise here, of continual verbal preservation of the original language text, He simply lied. That is what such an interpretation would demand.

So what relevance does this text have for a “doctrine of preservation?” In my opinion, absolutely none. When someone continues to present this passage in their doctrinal statements on preservation and in their teaching about preservation, they are simply displaying an ignorance of basic exegetical principles. One doesn’t have a higher view of Scripture by doing this. One rather reveals that they might not love Scripture as much as they claim to. If the passage is to be used in such a fashion, to support such a doctrine, someone must present an exegetical examination of the passage that can sustain that interpretation. Only after such a detailed exegesis can the passage legitimately be used as support for such a major doctrine. If such work has been done, this author has not seen it. All of the commentators in the present bibliography take the antecedent of both pronouns in verse 7 to be to God’s people. None of them even discuss a “preserved words” option of any kind.

Conclusion

This essay has examined the overall context of the psalm as a whole, noted its setting, and attempted a brief exposition of its meaning, while looking in particular at verses 6-7 in order to ascertain what contribution they make to the doctrine of preservation. What has been discovered is that David’s historical context, the historical context of the Israelite people for whom the song would be sung, and the literary context of the passage as a whole make it clear that the phrases are references to the preservation of God’s people, not his words. The syntactical and grammatical features have been noted which make it clear that the text is a reference to God’s promise to protect his people. Commentators both from past ages (including the KJV translators, though they are translators rather than commentators per se) and the present have affirmed that the phrase has historically almost always been taken in this sense. The conclusion of this essay is thus that the text has nothing whatsoever to say about the preservation of Scripture, and certainly nothing to say about textual transmission, or the endorsement of one Hebrew or Greek text over another.

There is always in theological disputes the temptation to want to find a proof text on every corner as it were. We are prone to want to write a reference down, and so feel confident that what we hold is a biblical position. But as men committed to handling Scripture well, with integrity, we have a responsibility to look closely at every text before we assert boldly, “Thus saith the Lord.” To do less may be to dishonor the Word we so claim to love. This is certainly so in our preaching. And it is even more so in our formulation of doctrines that we will put into doctrinal statements, and divide from others over, and preach with such passion. If in the study of such texts, we find that they do not support our positions, the man who loves Scripture will resist the temptation to twist the Bible to support what he believes, and will instead twist what he believes to match the Scriptures. May each of us be willing to, in the words of Haddon Robinson, “Bend our thoughts to Scripture,” rather than “Using Scripture to support our thoughts.”

Bibliography

Commentaries

Briggs, Charles Augustus. “A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms: Volume 1” in The International Critical Commentary Series (ICC). T&T Clark, Edinburgh, 1976.

Broyles, Craig C., “Psalms” in the New International Biblical Commentary Old Testament Series (NIBC). Hendrickson, Peabody, 1999.

Craigie, Peter, “Psalms 1-50 (2nd ed.)” Volume 19 in the Word Biblical Commentary Series (WBC). Nashville, Word Publications, 2004.

Delitzsch, F. and Keil, C.F. “Commentary on the Old Testament in Ten Volumes: Volume V – Psalms” (KD).

Goldingay, John, “Psalms Volume 1: Psalms 1-41” in the Baker Commentary on the Old Testament Wisdom and Psalms (BCOTWP). Baker, Grand Rapids, 2006.

Longman, Tremper III, and Garland, David E. (eds.) “The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Revised Edition, Volume 5: Psalms.” In the “Expositor’s Bible Commentary Series (REBC). Zondervan, Grand Rapids, 2008.

Murphy, James G. “Psalms: A Critical And Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms.” James Family Publishing, Minneapolis, 1977.

Phillips, John, “Exploring Psalms Volume 1: An Expository Commentary” in the John Phillips Commentary Series (JP). Kregel, Grand Rapids, 2002.

Ross, Allen, “A Commentary on the Psalms, Volume 1 (1-41),” in the “Kregel Exegetical Library” Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids, 2011.

Spurgeon, Charles. “The Treasury of David – An Expository and Devotional Commentary on the Psalms (Vol. 1)” Guardian Press, 1976.

Wilson, Gerald, “Psalms Volume 1” in The NIV Application Commentary (NIVAC). Zondervan, Grand Rapids, 2002.

Lexicons / Grammars

Brown, Driver, Briggs, “The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon” (BDB). Hendrickson Publishers, 1996.

Clines, David, J. A., “Concise Dictionary of Classical Hebrew” Dictionary of Classical Hebrew Ltd., OakTree Software, 2009.

Waltke, Bruce and O’Connor, M. “An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax.” Eisenbrauns, 1990.

Seow, C.L. “A Grammar for Biblical Hebrew” revised edition, Abingdon, Nashville, 1995.

Pratico, Gary D., and Pelt, Miles Van. “Basics of Biblical Hebrew” (2nd ed.) Zondervan, Grand Rapids, 2007.

Fuller, Russell T., and Kyoungwon, Choi, “Invitation to Biblical Hebrew: A Beginning Grammar” in the Invitation to Theological Studies Series. Kregel, Grand Rapids, 2006.

Peterson, David L., and Richards, Kent Harold. “Interpreting Hebrew Poetry” in the “Old Testament Series.” Fortress, Minneapolis, 1992.

Footnotes

[1] Ross, pg. 351.

[2] Longman and Garland, REBC, pg. 165.

[3] Longman and Garland, REBC, pg. 165. Delitzsch follows essentially the same chiastic structure, noting the central place of God’s promise and the psalmist’s reflection on it.

[4] Ross, pg. 351.

[5] See Craigie, pg. 137, and Ross pg. 352.

[6] Keil and Delitzsch, Pg. 198.

[7] REBC, Pg.168-169.

[8] Briggs, ICC, Pg. 94.

[9] BDB, pg. 57.

[10] Deut. 33:9; Ps. 119:11, 38, 50, 67, 103, 140, 158, 162, 172; Ps. 138:2; Isa. 29:4.

[11] This is not to impugn in any way on a doctrine of verbal inspiration, which rest on wholly other grounds. Rather it is to explain that this noun is not typically referring to specific words of a verbal character as much as to the speech or oracle as a whole. The plural should not be then pressed to demand a reference to verbal perfection, when that isn’t in sight with this word.

[12] One should note that my work has been with academic commentaries whose work is based on the Hebrew text. One could perhaps find a pastoral or devotional level commentary based only on the English text that might make that jump, though I’ve not seen them.

[13] See definition in BDB, pg. 1036, HALOT.

[14] Ross, pg. 358.

[15] The English language can retain gender in the possessive case, (his/hers), but not in the objective case.

[16] See Waltke-O’Conner, pg. 302.

[17] Waltke-O’Connor, Pg. 291.

[18] For the independent object pronoun functioning as the direct object of a clause, see Seow, pg. 99.

[19] I am indebted to Harold Bradley for this insight. It had not occurred to me to examine the previous English translations here until I read his excellent exposition of the whole passage in an unpublished paper he submitted to Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, after which point I revised my paper to include this insight. I should also note (in this revised note) that his interaction with Strouse makes me realize I still need to emend several statements in this essay relating to the KJVO interpretation, which I had written before reading the article by Strouse.

[20] We will demonstrate this point more fully in Part II.

[21] Waltke-O’Connor Pg. 119-124. These conditions include plurals of extension and honorific plurals, among others. Although, if the plural in verse six is taken as a collective, it would be possible, since singular pronouns can refer to collective plural nouns. But even then, it would still be more likely to take it as referring to an actual singular.

[22] Goldingay, BCOTWP, pg. 201.

[23] See marginal note of 1611 KJV. In fact, in Psalm 12 alone, the KJV translators three times provide alternate translations of the text in the margins, and five times give a more literal rendering of the Hebrew text that would be necessary to understand the sense. This was their common practice. It was also their common practice to note textual variants in the places where they were aware of them. If they saw a promise that meant the words of the Greek or Hebrew text were to be preserved in a particular Greek text, or that the words of the KJV couldn’t be changed, they seem to have strangely contradicted it in their own notes, even in this very psalm.

[24] Delitzsch refers here to the variant reading “us” found in the LXX and some Hebrew manuscripts. This essay will comment only on the MT reading, which he defends.

[25] Keil and Delitzsch, Pg. 197.

[26] If one considers the great Athanasius, to whom we owe so much of our Christology, or Chrysostom, or Theodoret, Valerian, or Augustine, it appears that the early church never took the referent as being to God’s words. No one ever suggested anything else.

[27] Spurgeon, Pg.

[28] BDB, pg. 189-190.

[29] This is how Ross takes it, pg. 353, as well as many others.

[30] Clines, pg. 315.

Thank you very much for this most valuable insight on the translation history of Psalms 12:6-7.

Concerning this same text, one study note of the NET Bible states : « Some Hebrew mss and ancient textual witnesses read “us,” both here and in the preceding line. » This statement is corroborated by notes in the NBS (French equivalent of ESV) and Semeur (French equivalent of NIV).

Hence the NRSV 2021 reads : « You, O Lord, will protect us; you will guard us from this generation forever. »

Do you have any information on the identity of the *other* Hebrew manuscripts which contain this « us-us » variant ?

Apparently it’s not the two Dead Sea scrolls containing this Psalm (11Q7 and 5/6HevPs) :

http://dssenglishbible.com/psalms%2012.htm

I don’t have a BHS and even if I did I can’t read Hebrew.

As for the « ancient textual witnesses » to which the NET note refers, the NBS and Semeur notes specify that it is « ancient versions » (plural), i.e., ancient translations. On this matter, I found the “New English Translation of the Septuagint”, which reads : « You, O Lord, you will guard us, and you will preserve us from this generation and forever. »