We all know the story of the three Hebrew children thrown into the fiery furnace in Daniel chapter three. In fact, some of you are singing “I’m Rack, I’m Shach, I’m Benny!” even as I mention it. (Shame on you vegetable lovers!) Surely, the image of the fourth man in the fire is a continually comforting one to the believer enduring trials. When three faithful Hebrew refused to bow to an idolatrous image, King Nebuchadnezzar followed through on his threat to throw them bound into the fiery furnace. He knew he only threw three men in, bound. But he found four men, unhurt, and unbound.

Who Was This Fourth Man In The Fire?

The text reads;

“Then Nebuchadnezzar in furious rage commanded that Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego be brought. So they brought these men before the king.Nebuchadnezzar answered and said to them, “Is it true, O Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, that you do not serve my gods or worship the golden image that I have set up? Now if you are ready when you hear the sound of the horn, pipe, lyre, trigon, harp, bagpipe, and every kind of music, to fall down and worship the image that I have made, well and good. But if you do not worship, you shall immediately be cast into a burning fiery furnace. And who is the god who will deliver you out of my hands?”

Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego answered and said to the king, “O Nebuchadnezzar, we have no need to answer you in this matter. If this be so, our God whom we serve is able to deliver us from the burning fiery furnace, and he will deliver us out of your hand, O king. But if not, be it known to you, O king, that we will not serve your gods or worship the golden image that you have set up.”

Then Nebuchadnezzar was filled with fury, and the expression of his face was changed against Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. He ordered the furnace heated seven times more than it was usually heated. And he ordered some of the mighty men of his army to bind Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, and to cast them into the burning fiery furnace. Then these men were bound in their cloaks, their tunics, their hats, and their other garments, and they were thrown into the burning fiery furnace. Because the king’s order was urgent and the furnace overheated, the flame of the fire killed those men who took up Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. And these three men, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, fell bound into the burning fiery furnace.

Then King Nebuchadnezzar was astonished and rose up in haste. He declared to his counselors, “Did we not cast three men bound into the fire?” They answered and said to the king, “True, O king.” He answered and said, “But I see four men unbound, walking in the midst of the fire, and they are not hurt; and the appearance of the fourth is like a son of the gods.”

Then Nebuchadnezzar came near to the door of the burning fiery furnace; he declared, “Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, servants of the Most High God, come out, and come here!” Then Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego came out from the fire. And the satraps, the prefects, the governors, and the king’s counselors gathered together and saw that the fire had not had any power over the bodies of those men. The hair of their heads was not singed, their cloaks were not harmed, and no smell of fire had come upon them. Nebuchadnezzar answered and said, “Blessed be the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, who has sent his angel and delivered his servants, who trusted in him, and set aside the king’s command, and yielded up their bodies rather than serve and worship any god except their own God. Therefore I make a decree: Any people, nation, or language that speaks anything against the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego shall be torn limb from limb, and their houses laid in ruins, for there is no other god who is able to rescue in this way.” Then the king promoted Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego in the province of Babylon.”

(Daniel 3:13–30 ESV)

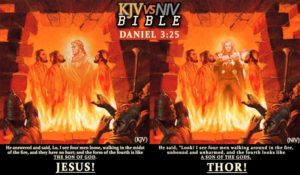

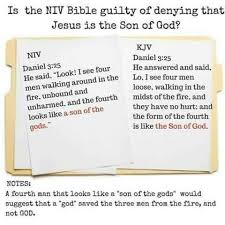

The KJV, differing from the ESV quoted above, claims that, “the form of the fourth is like the Son of God” (Dan. 3:25 KJV), which is a direct statement about Jesus, the Second Person of the Trinity, being in the fire with the Hebrew children. On the other hand, the NIV, and most other modern translations, read something like, “and the appearance of the fourth is like a son of the gods (Dan. 3:25 ESV).”

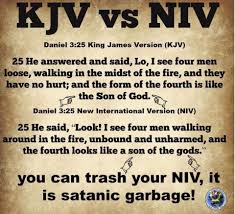

I regularly see comparisons of Dan 3:25 NIV/KJV in my news feed. A meme comparing them seems to go around every so often in “seasons.” One form suggests that the NIV has “taken Jesus out” of Daniel 3:25, and that this is a “big deal.” I even recall hearing one pastor tell me that this passage is “the” reason why we should all use the KJV instead of other translations, because the KJV points to Jesus, and all the others have “removed Jesus” from the passage! Examples are easy to find with a simple google search, variously claiming that the NIV promotes Thor worship, denies the deity of Jesus, or is “satanic garbage” as a result of its reading in Dan. 3:25;

What is really going on here? Which translation is right? Who really was the fourth man in the fire? Is this really such a big deal? And is it a matter that justifies the kind of language in such memes?

First, I’d say to those sharing sharing memes like that one, or raising the question, in one sense, thank you for sharing the post. I think comparing translations like that can be very helpful. The King James translators, (in their preface defending the practice of placing thousands of alternate translations in the margins) noted that,

Therefore as St. Augustine saith, that variety of Translations is profitable for the finding out of the sense of the Scriptures: so diversity of signification and sense in the margin, where the text is not so clear, must needs do good, yea is necessary, as we are persuaded.

Augustine knew that there is no perfect way to translate much of Scripture, and had suggested that the wise reader always compare different translations to make sure that he understands the sense of Scripture, not just the interpretation of the translator. The KJV translators quite agreed, as do I. So again, thank you for sharing. I think it’s important to understand why translations differ in any particular instance, so that we can understand what’s at work behind the scenes.

There are actually two different questions at issue when we come to the questions of this passage. The first is the theological one – that is, who do we understand the “fourth man in the fire” to have been? We might call this the question of theological interpretation. The second is the related, but distinct, matter of how to translate the phrase the King uses to refer to him. This might be considered the question of who the King regarded the being to be, and which perspective should be reflected in an English translation of the phrase, or the exegetical interpretation.

Who Was In The Fire? – The Question Of Theological Interpretation

As to the first question, “Who was in the fire?”, it may surprise some readers to know that this is a highly debated matter among commentators. There is a long tradition in Christian history of identifying the “fourth man” as a theophany, or, more particularly, what is sometimes called a “Christophany” (an appearance of the pre-incarnate Christ). This interpretation of the text goes back a long way in church history, and for many conservatives, it is probably the only understanding of the passage they are familiar with. But there is an (even longer) tradition of Jewish commentators (and Christian commentators who follow their lead) that identify the being with some other angelic being or form of divine presence or agent (often along the lines of the common “Angel of the LORD” found at various points throughout the OT). James Montgomery, in the Older ICC volume, notes that, “As to the theological interpretation of the son of God, the Jewish commentators identify him simply as an angel…”. But he also notes that, “Early Christian exegesis naturally identifies the personage with the Second Person of the Trinity…But this view has been generally given up by modern Christian commentators” (ICC, Daniel, pg. 215).

Goldingay, in the more recent WBC volume, notes that the phrase, “might for Nebuchadnezzar suggest an actual god. Similarly God’s aide [the angel of the Lord] might signify in effect God himself; cf. Yahweh’s [angel], e.g., Exodus 3:2. Isaiah 43:1-3, indeed, has promised God’s own presence when Israel walks through the fire. Nevertheless to Jews [the Hebrew phrase son of the gods/Son of God/Divine being] would indicate a subordinate heavenly being. Cf. the supernatural watchman…of [Daniel] 4:10, 14, 20 [13, 17, 23], and the humanlike heavenly interpreters and leaders of chapters 7-12. In such a context God’s [angel], too, will denote a non divine heavenly being” (Goldingay, John, WBC “Daniel,” pg. 71).

Tremper Longman puts an even finer point on the question.

That God rescued the three Jews no one is in doubt, but who was that ‘fourth [who] looks like a son of the gods” (v. 25)? As in chapter 2, Nebucadnezzar is moved from anger to praise toward God and his followers. In his concluding speech, he again mentions the mysterious fourth person. When he first saw the figure, he labeled him ‘a son of the gods’; now he calls him God’s ‘angel’ (v. 28). His dual description has launched a debate that continues to the present day…we must remember that the narrative places these two descriptions in the mouth of Nebuchadnezzar, who is not an Israelite theologian. Relying on his words, we are thrown into a quandary: was this God himself as ‘son of the gods” might lead us to believe, or an angel? In one sense, it does not make any difference. Even if the fourth figure was an angel, it was God’s angel; God is still the redeemer. Even Nebuchadnezzar recognizes this. He further acknowledges that the three have been right to obey this God rather than a king like him.

– NIVAC, Daniel, Pg. 102-103.

He later takes up the question again, and asks,

Where does the Christian…find the moral and religious strength to make such a courageous stand? From Jesus Christ. Jesus himself was put on trial for his religious claim that he was the Messiah. Facing death himself, he refused to capitulate, dying on the cross (cf. Matt. 27:11-14). But was Jesus at the heart of the hope of the three friends as they faced death in the furnace? It is difficult to say how specifically their hope focused on the coming Savior, the Messiah. They trusted in the saving power of God, but it is provocative to reflect on the way God choose to deliver the three from the fire. Calvin pointed out that if God wanted, he could have extinguished the flames of the fire in order to save the three men. He saved them in the fire, not from the fire. They were in the very jaws of death. Moreover, he could have saved them without further fanfare, simply having them walk out of the fire unscathed, but instead chose to save them by the presence of a ‘fourth [who] looks like a son of the gods” vs. 25).

Was this ‘fourth’ being Jesus, as many interpreters from the earliest Christian times have suggested? It is impossible to be dogmatic unless one insist that every incarnate appearance of God must be the second person of the Trinity. It is safer to say that what we have here is a reflection of Immanuel, ‘God with us.’ God dwelt with the three friends in the midst of the flames to preserve them from harm. In this sense, the Christian cannot help but see a prefigurement of Jesus Christ, who came to earth to dwell in a chaotic world and who even experienced death, not so that we might escape the experience of death but that we might have victory over it.

– NIVAC, pg. 112.

How Should We Translate The Phrase? – The Question Of Exegetical Interpretation

When we approached the theological question, we asked only who was actually in the fire, from our later and more mature vantage point. And it turns out, that’s a controversial question, and we can’t say for sure, though we can be sure that the point of the text is the same either way – God walks with us through the fire. But even if we concluded that it was in fact the pre-incarnate Christ who was in the fire (a position I lean towards), that does nothing to settle the second question. That is, how should the phrase referring to this fourth man be translated in our English Bibles? The reason this is so is because it is generally agreed that the purpose of a translation is to give the meaning of the text as understood by its original author, not as it came to be interpreted in later Christian times. Let me explain.

Translating The Text

The text being translated by both the NIV and the KJV at this passage is exactly the same. It is an Aramaic section of the Masoretic text. The KJV translators were using the 1525 Bomberg edition of the Hebrew text, the NIV was using the more modern BHS, but both are identical at this point (and almost all others). The text reads a simple three-word phrase;

דָּמֵ֖ה לְבַר־אֱלָהִֽין׃ ס

Or, literally, “like a son of the gods.” The word for “God/gods” is elohin, the Aramaic (Chaldee) equivalent of the Hebrew Elohim. The word is plural, not singular, so grammatically speaking the NIV is being more literal by translating it with a plural (“gods”) rather than a singular (“God”). But sometimes, when used of the one true God, the word can be plural in form but singular in meaning (somewhat like what’s known as a “plural of majesty”). Although it has been argued that such a singular sense is actually grammatically impossible here in this instance (see the note in Goldingay’s WBC commentary, pg.67). More often it is a true grammatical plural, referring to “gods.” HALOT, the standard Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon for biblical studies, notes that the word can refer to “the God of Israel” but also can refer (2ba) to “the gods of other nations (in Daniel always Babylonian gods)” and notes that the Masoretic Text has it as a plural here, “preferring the idea that Nebuchadnezzar was a polytheist,” and they note that in this passage it refers to “a divine being, an angel.”

One can see several uses of this word in this very passage, to get a sense of the difference. For example, in 3:14 the KJV translates the same word “gods,” then in 3:17, the same word as “God,” and again in 3:18, it is “gods” in the KJV. All of these are the same word. Both “God” and “the gods” (and even “angel”) are legitimate translations at times. Probably either is possible here. The context and intent of the speaker is the key.

So what is the context, and who is the speaker? It is important to remember, as Tremper Longman pointed out above, that verse 25 is not in the mouth of Daniel as a narrator and biblical writer. This is not Daniel’s description of what he sees in the fire. Rather, the words are on the mouth of the pagan King, Nebuchadnezzar. Daniel (who is not present in this story, but nonetheless narrates it as an inspired historian) is a good historian. He reports what happened accurately, without embellishment, and without exaggeration. So what happened historically? The King saw another being in the fire with the three children, and spoke of it according to his own viewpoint, from his own limited understanding. From his viewpoint, what he saw was, “a son of the gods.” This common phrase simply meant an angel or “divine being” of any kind (see Goldingay, WBC, pg. 64). Daniel makes clear in verse 28 that what Nebuchadnezzar thought he saw was just such a being;

Then Nebuchadnezzar spake, and said, Blessed be the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, who hath sent *his angel,* and delivered his servants that trusted in him, and have changed the king’s word, and yielded their bodies, that they might not serve nor worship any god, except their own God.

The king thought it was an “angel” or a divine being, what he would refer to as “angel” or a “son of the gods.”

Tracing Historic Translations Of The Text

Thus, for example, the Coverdale Bible of 1535 translated the phrase in verse 25,

“and the fourth is like an angel to loke vpon.”

The Geneva Bible rendered the text;

“and the forme of the fourth is like the sonne of God.”

but left a study note that explained that this actually was just another way to refer to an angelic being of any kind;

For the Angels were called the sonnes of God, because of their excellencie: therefore the Kīg called this Angel, whome God sent to comfort his in these great torments, the sonne of God.

The Matthew’s Bible of 1549 that revised it likewise read,

“and the fourthe is lyke an angell to loke vpon.”

The Bishop’s Bible, likely following the Geneva Bible, had changed this to,

“and the fourme of the fourth is like the sonne of God.”

The KJV is itself simply a revision of the 1602 Bishop’s Bible, which reads as above, “like the sonne of God,” but adds a marginal note to clarify what is meant, “That is, an angel of God.” Normally, when revising the Bishops text, they just left the text the same. But here, they chose to remove the marginal note, leaving “sonne of God” in the text without capitalization.

The 1611 KJV reads essentially the same as the Bishop’s Bible here, and clearly means the same thing, but without the clarification of its note. That is, the 1611 KJV intends to teach that this was an angelic being, not that this was Christ. But they removed the marginal note of the Bishop’s text which made this clear. This created an ambiguity that a later editor missed. At some point (after 1638, the latest old edition I checked, but before the Scrivener 1873 Cambridge Paragraph Bible), the meaning of the phrase “son of God” as an angelic being was lost, and “Son” was capitalized, thus making it a reference very directly and specifically to Christ.

These translations from Bible’s preceding the KJV should do away with any slanderous claim that the NIV is attempting to “remove Jesus” from the passage here. Jesus wasn’t in the passage in English in the KJV in 1611, and wasn’t in the passage at all in English Bibles until a later editor misread the KJV!

Note that Daniel reported what was actually said historically, not our later and more accurate theological interpretation of what was actually taking place. Today, as Christians, we can look back with a full Bible and a full revelation, and we understand a doctrine called the Trinity. We know that the one true God is a three-in-one Being; Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. But this was not yet revealed in Daniel’s time (in a later vision for example, Daniel sees “the Ancient of Days” or God, and “the Son of Man,” a different mysterious figure who Jesus later revealed prefigured Himself). God’s revelation unfolds over time. The revelation that the single God Yahweh has a Son who shares fully in His Divine name would not take place until Jesus came in the incarnation, and it didn’t come first to a pagan King. If Nebuchadnezzar had actually said, “Look! The one true God has a Son who is also God!” then God would have been giving revelation about himself to a pagan King that he wouldn’t even give to His own people until some 500 years later. I think it rather unlikely that such a pagan King had a higher revelation from God (and in any case, verse 28 in the KJV makes clear that he did not). As Christians with full revelation, we can know Who was in the fire. But as translators, one could make the case that we should respect Daniel’s own intentions as a biblical writer. Daniel was a good historian, and we should not, in my opinion, create an instance of him being a bad historian (interpreting rather than reporting what the King had said).

John Calvin took a similar track as the Geneva note listed above, understanding that “son of a god/God” was simply a way of referring to an angelic being, and arguing that Nebuchadnezzar could not have understood otherwise. He explained;

John Calvin

But Nebuchadnezzar says, four men walked in the fire, and the face of the fourth is like the son of a god. No doubt God here sent one of his angels, to support by his presence the minds of his saints, lest they should faint. It was indeed a formidable spectacle to see the furnace so hot, and to be cast into it. By this consolation God wished to allay their anxiety, and to soften their grief, by adding an angel as their companion. We know how many angels have been sent to one man, as we read of Elisha. (2 Kings 6:15.) And there is this general rule—He has given his angels charge over thee, to guard thee in all thy ways; and also, The camps of angels are about those who fear God. (Ps. 91:11, and 34:7.) This, indeed, is especially fulfilled in Christ; but it is extended to the whole body, and to each member of the Church, for God has his own hosts at hand to serve him. But we read again how an angel was often sent to a whole nation. God indeed does not need his angels, while he uses their assistance in condescension to our infirmities. And when we do not regard his power as highly as we ought, he interposes his angels to remove our doubts, as we have formerly said. A single angel was sent to these three men; Nebuchadnezzar calls him a son of God; not because he thought him to be Christ, but according to the common opinion among all people, that angels are sons of God, since a certain divinity is resplendent in them; and hence they call angels generally sons of God. According to this usual custom, Nebuchadnezzar says, the fourth man is like a son of a god. For he could not recognise the only-begotten Son of God, since, as we have already seen, he was blinded by so many depraved errors. And if any one should say it was enthusiasm, this would be forced and frigid. This simplicity, then, will be sufficient for us, since Nebuchadnezzar spoke in the usual manner, as one of the angels was sent to those three men—since, as I have said, it was then customary to call angels sons of God. Scripture thus speaks, (Ps. 89:6, and elsewhere,) but God never suffered truth to become so buried in the world as not to leave some seed of sound doctrine, at least as a testimony to the profane, and to render them more inexcusable—as we shall treat more at length in the next lecture.

– John Calvin and Thomas Myers, Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Daniel, vol. 1 (Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 2010), 230–231.

That’s not to say I’m demanding that we “correct” the modern KJV here. Far from it. The KJV in its modern printing is explaining quite accurately the theological truth of the Trinity. The KJV does not accurately present what Daniel intended when he wrote, but it does accurately reflect an Anglican, orthodox understanding of the Trinity, as developed and expressed long after Daniel’s time. Probably, one could read the verse from the KJV, and just read vs. 28 to clarify what the King thought he saw, and Who we know was really there. But at the least, the NIV should certainly not be attacked here for translating the same text in a more literal way grammatically, and for representing Daniel as being an accurate historian who didn’t creatively interpret what he recorded, but accurately wrote what was said, rather than putting words in someone’s mouth that they likely didn’t utter.

Both translations should by understood for what they intend to do, and neither deserves censure at this point, (contra the memes that go around suggesting that this difference is a “big deal” or is “removing Jesus”). The NIV is translating what the King actually said. If one wants their translation to reflect the intent of the original biblical author, the NIV is spot on at this point. The KJV is interpreting that statement not as it was originally spoken but as it came to be understood by later Christian theologians. If one wants their translation to reflect later theological formulations from the 17th century, the KJV is spot on at this point. Both can be valid in some ways.

But Didn’t Nebuchadnezzar Adopt Jewish Monotheism?

An interesting article making similar points as I have made here can be found at KJVOnly.org here. An attempt to defend the KJV reading, which I think quite fails, can be read at the KJV Today site here. Note that it is essential to that defense that the King did not mean to say that the fourth man in the fire was Jesus. So the KJV Today article is no support for an attack on the NIV for “deleting Jesus” or any such thing. However, the KJV Today article attempts to claim that since Nebuchadnezzar uses the phrase, “the most high God” in verse 26, he must of necessity have been referring to the monotheistic understanding of the Jewish God. This would still miss the point that Jewish monotheism is not Christian Trinitarianism, but even as much as it says is not technically accurate. Goldingay points out,

The title ‘God Most High’ (vs. 26) is another expression at home on the lips of either a foreigner (3:32; 4:14; 31 [4:2, 17, 34]; Gen. 14:18-20; Num. 24:16; Isa. 14:14) or a Jew (Dan. 4:21-29 [24-32]; 5:18, 21; 7:18-27; Gen. 14:22; Deut. 32:8; Psalms), though its nuances for each would again differ. To both it suggests a God of universal authority, but of otherwise undefined personal qualities. For a pagan [like Nebuchadnezzar], it would denote only the highest among many gods, but as an ephitet of El it was accepted in early OT times and applied to Yahweh, so that for a Jew it has monotheistic (or mono-Yahwistic) implications.

– WBC, pg. 71-72.

And Baldwin, among many other voices, likewise agrees, noting;

This title for God is often found in the mouth of non-Jews (Gen. 14:19; Num. 24:16; Isa. 14:14). There is nothing unlikely in the edict, which does no more than declare legal in the empire the religion of the Jews.”

– Baldwin, J. G. (1978). TOTC Daniel: An Introduction and Commentary (Vol. 23, p. 118). Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

What Does The Story Say To Us Today?

Regardless of how we answer both of the questions above, the point of the passage remains the same for us as believers. Daniel is writing his work near (or just after) the end of the Babylonian captivity of the children of Israel. This surely was one of the more difficult experiences of their existence. And Daniel knew that they would need reminded that even in their chastisement, God was never apart from them. And so he recounts for them the story they had told already for a generation. A story of the proto-typical time, in their recent memory, when God had shown that he never abandons his children to face the fire alone. He walks with them through it, just as he had promised (Is. 43:1-3). As Calvin noted, he saved them in the fire, not from it. And this has always been his way with his children who suffer in this broken and fallen world. He still saves in the fire. Goldingay notes,

The king who thought that no god could save the confessors from his power is the one who now perceives God’s intervention….The three have not been delivered from the fire, but they are delivered in the fire (c.f. Rom. 8:37) (Phillip). The life of blessing and success that is their destiny is reached, not by way of costless and risk-free triumph but by the way of the cross. They are free, looking as if they are enjoying a walk in the garden… It is four unbound (vs. 25) who contrast with three bound. The deliverance comes about through the presence of a fourth person in their midst. The divine aide who camps round those who honor God and extricates them from peril (Ps. 34:8 [7]) enters the fire himself to neutralize its capacity for harm by the presence of his superior energy. God’s promise, “I will be with you” characteristically belongs in the context of afflictions and pressure (Exod. 3:12; Isa. 7:14; 43:1-3; Matt. 28:20; see also Ps. 23:4-5). The experience of God’s being with his people not only follows on their commitment to him, rather than preceding it; it comes only in the furnace, not in being preserved from it…

– WBC, pg. 74-75.

Tim Keller points out, in words that can conclude our brief look at the text;

In perhaps the most vivid depiction of suffering in the Bible, in the third chapter of the book of Daniel, three faithful men are thrown into a furnace that is supposed to kill them. But a mysterious figure appears beside them. The astonished observers discern not three but four persons in the furnace, and the one who appears to be ‘the son of the gods.’ And so they walk through the furnace of suffering and are not consumed. From the vantage of the New Testament, Christians know that this was the Son of God himself, one who faced his own, infinity greater furnace of affliction centuries later when he went to the cross. This raises the concept of God ‘walking with us’ to a whole new level. In Jesus Christ we see that God actually experiences the pain of the fire as we do. He truly is God with us, in love and understanding, in our anguish. He plunged himself into our furnace so that, when we find ourselves in the fire, we can turn to him and know we will not be consumed but will be made into people great and beautiful. ‘I will be with you, your troubles to bless, and sanctity you to your deepest distress.’

– Walking With God Through Pain And Suffering, pg. 9-10.

Comments