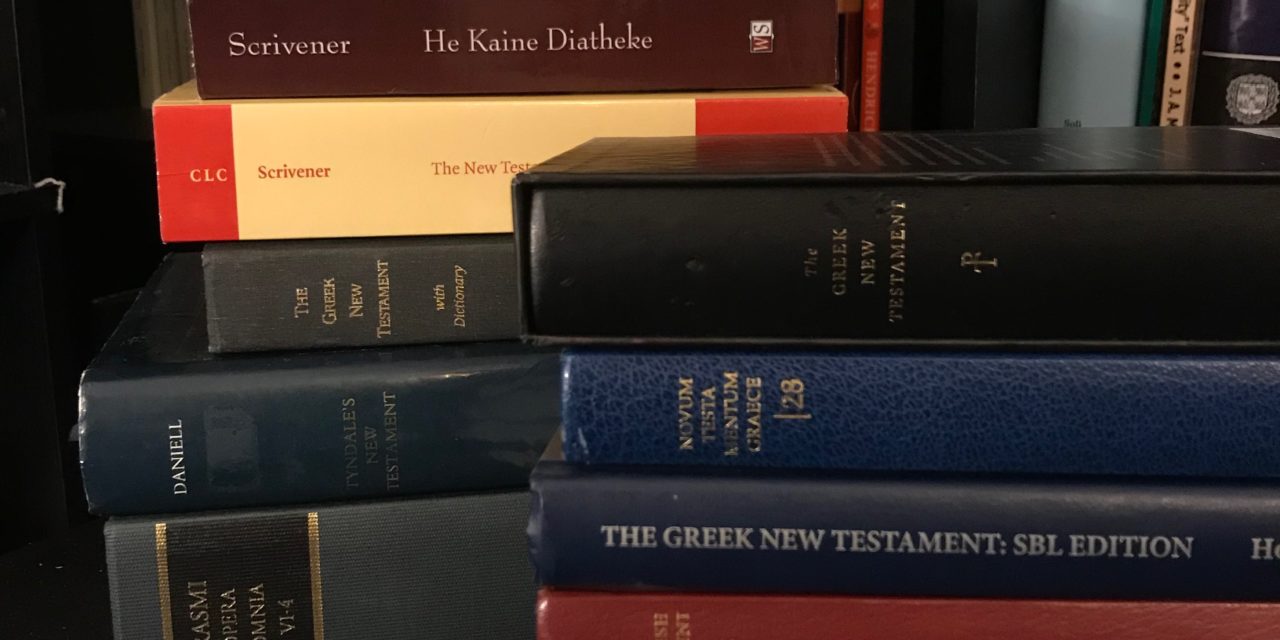

New editions of the Greek NT come out on a pretty regular basis. Over 1,000 different editions have been printed since 1516. Is this because the text of the NT that we have can’t be trusted? Is it because publishers just want to steal more of your money? Like an IPhone update that changes almost nothing but charges you an arm and a leg? Actually, it’s exactly the opposite.

We don’t have the original autographs of any of the NT documents. What we do have is later handwritten copies, (we call handwritten copies “manuscripts,” or mss. for short), all of which differ slightly from one another, because of errors and alterations made by each individual copyist. We use these to reconstruct the original wording of the original NT books as best we can. This “reconstruction” is known as “textual criticism” or NTTC. This data is then complied into an eclectic, printed text of the Greek NT, from which translations are then made. For the *vast* majority of the text of the NT, no “reconstruction” is necessary, because essentially all of the mss have exactly the same wording. The questions come in the small places where the mss have different wording. Even in those places, it’s not as though we’ve “lost” the Word. It’s just that we sometimes have two or more different wordings of the passage as found in various mss., and we aren’t always sure which represents the original wording, and which is a scribal alteration.

So why do these printed NT texts continue to constantly be updated? Several factors come into play;

Factors Relating To Why The NT Needs Regularly Updated

- One is the discovery of new manuscripts. Newly discovered manuscripts mean more data, which gives us a better picture of the wording of the original text of the NT. It would be irresponsible not to take into account this new data as it is discovered, even if it takes some time for data from newly discovered manuscripts to filter into editions of the Greek NT, and then from them into English translations.

- Another is a more accurate reading of the data in the manuscripts we have. For example, Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus is an important fifth century palimpsest manuscript that we’ve had for a long time. But no one was able to decipher it, so its text-critical data couldn’t be accessed or evaluated. Until a bright young scholar named Constantin Tischendorf launched his NTTC career in the 1840s by carefully examining the manuscript, deciphering its readings, and publishing the results. The manuscript had been there for a long time, but we had to get a more accurate reading of it. We continue to get better and better at reading ancient manuscripts, even those whose data seems hidden below the surface. Digitization has helped this factor immensely. We can see readings more clearly now than we once did in mss that we’ve had for a long time (and sometimes the mss. decay, making them less readable – another reason that digitization like that of Dan Wallace, the CSNTM and their mission to preserve the Word of God is so important).

- Another is the further collating of the manuscript data that we’ve always had (it’s an ongoing process – Philemon, Jude, and Revelation are the only NT books where all of the manuscript data has been completely collated). Collating is what happens when we examine every single letter of a ms. against another text to note where they differ. Every single difference of a single letter is known as a “textual variant.”

- But finally, as all this data grows, the relationships between the data are examined again and again. And our understanding of those relations continually gets tweaked by new data and continued study of old data.

- Thus, new insights are discovered, and text-critical methodology thus matures. As it matures, in slight ways, edits are made to the final text that is produced by that methodology using all that data.

A Brief History Of Updating The New Testament

Erasmus of Rotterdam

The 1535 “Annotations” of Erasmus of Rotterdam.

All of these factors have been at work since 1519. Erasmus printed a Latin/Greek diglot in 1516. It had his revision of the Latin Vulgate on one side, and the Greek text which he rather haphazardly created simply to substantiate his revisions of the Latin on the other side. While the Greek column wasn’t all that important to him, it was the first Greek NT to ever be published. And it quite literally changed the world. He added over 1,000, Annotations (like endnotes), many of which explain the many text-critical decisions he had to make when his data differed from one another. He explained how he was often not sure which reading was original. And he explained why he sometimes preferred the reading of the Latin Vulgate over his handful of Greek Mss (for example, in Acts 9:5-6, I John 5:7, and dozens of other passages). His text was a hodge-podge mixture of mostly Byzantine readings, scores of Latin Vulgate readings, and numerous minor editorial errors that wouldn’t be noticed for several hundred years (like this one in Rev. 1:8, where he accidentally deleted “God” from the text, and it didn’t get fixed till the 19th century).

But he continued to amass more data, continued to study the relationships of manuscripts to each other, and matured in his NTTC approach. Thus, another edition was required in 1519, another in 1522, then in 1527, up until 1535, when he published his final edition. His annotations pointing out textual variants and orthographical data had at least doubled in size by then, and were now printed as their own separate volume. His various editions can all be accessed here. Scrivener shared (and corrected) the evaluation of Mill about the changes in his editions (data now set out more accurately in the 10 ASD volumes);

“He estimates that Erasmus’ second edition contains 330 changes from the first for the better, seventy for the worse…that the third differs from the second in 118 places… the fourth from the third in 106 or 113 places, ninety being those from the Apocalypse just spoken of….The fifth he alleges to differ from the fourth only four times, so far as he noticed…but we meet with as many variations in St. James’ Epistle alone.

– Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Fourth Edition, 2:187.

In his Annotations, we can watch on as Erasmus begins to develop the principles of NT Textual Criticism. In fact, many of the principles of modern textual criticism find their genesis in his work, as Jan Krans points out. His work was far from perfect. But he birthed the discipline, which was still in its infancy when he published his final edition. He is clearly the father of modern New Testament Textual Criticism.

Robertus Stephanus and the Editio Regia

While starting with Erasmus as a base, Stephanus also continued to improve the text. He had more mss data than Erasmus. He ultimately included data from 16 Greek mss, including those used by Erasmus, in his apparatus (a system of abbreviations that lets an editor present mss data very concisely). This basically doubled the data Erasmus had. And the discipline matured in his handling of textual variants (reflected in his apparatus more than the text itself). Four different editions were the result, in 1546, 1549, 1550, and 1551 (see the 1550 Edito Regia here). His was the first printed Greek text to use an apparatus. Thus, while Erasmus published the first eclectic Greek text, Stephanus can be credited with printing the first critical apparatus. Scrivener notes the differnces between each edition; “My own collation of the [first two editions] gives 139 cases of divergence in the text, twenty-eight in punctuation. They differ jointly from the third edition 334 times in the text, twenty-seven in punctuation” (Scrivener, A Plain Introduction, 2:189). Stephanus’ editions can be accessed by anyone here.

Theodore Beza

Theodore Beza, the son in law of John Calvin and his successor in Geneva, took the discipline forward with his numerous marginal notes (see on any page of his works). Beza went through the same process, adding a little more mss data (he ultimately included data from 19-25 Greek mss, if we count those of Erasmus and Stephanus as well, which he had access to via the collations of Stephanus), re-evaluating textual variants, and maturing the discipline of textual criticism (again, mostly seen in his notes rather than the text itself). Thus 11 different editions (by one count) were forthcoming from him. Each edition can be accessed here. And the discipline matured a lot at his hand, as we see in his various editions and their notes. Careful study of his textual method, specifically, his conjectural emendation, is displayed by Jan Krans here. Scrivener, again, noted that early estimates of the differences between his editions were too low.

The KJV Translators As Textual Critics – Meddling With Men’s Religion

In 1604, King James I of England commissioned a revision of the 1602 edition of the Bishop’s Bible. Rule 1 specifically stated that the Bishops’ Bible taken as a base was to be revised as little as possible: “The ordinary Bible read in the Church, commonly called the Bishops Bible, to be followed, and as little altered as the truth of the Original will permit.” See an early copy of the rules in the British Library viewer for MS. BL. Add. 32092, f. 204r-v here. That revision is what we now call “The King James Bible.” (See title page in BL viewer here). The Translators made use of a handful of the numerous texts that had been produced by these three “giants” and fathers of the discipline of NTTC (they relied most heavily on the 1598 Beza, but sometimes followed Erasmus, and occasionally the Stephanus). The data they had should have made them aware of perhaps a few thousand textual variants. But they didn’t spend much time in the “scholia” (the footnotes to the printed texts explaining those variants). The more academic questions about textual criticism raised in those notes wasn’t their primary concern – producing a revision of the English Bible was.

But that doesn’t mean textual issues were totally unknown. They did note scores of textual variants in the marginal notes of the 1611. And they might have noted more if not for the King’s order against notes. One of the translators, John Bois, was something of a linguistic legend. He spoke Hebrew at the age of 5, and learned Greek and Latin shortly thereafter. His mind was the stuff of legends. He exclaimed during the revision process in frustration, “Read the Greek Scholia!” He was a rare voice that thought they should be giving more attention to the text-critical issues raised in the notes of Erasmus, Stephanus, and Beza.

He also took notes during one stage of the work at Stationer’s Hall (in this room here, image 39), and they can be read today. I’ve spent quite a bit of time with them. They are laced with references to Beza and Erasmus and the text critical questions they raised. They reveal the KJV translators doing their own text-critical work that created the Greek text behind the KJV, often disagreeing with one another (he sometimes records who disagreed with who). Bois of course had his own disagreements, and published a 2-volume work evaluating the text-critical choices of Beza’s edition (which the KJV translators opted to follow more closely than any other). That is to say, he was at times critical of the textual choices that ultimately created the KJV. And he wasn’t the only one. For example, one of the greatest Hebraists of that age, Hugh Broughton, was very upset at how often the KJV chose to depart from the Hebrew Masoretic Text of the Old Testament and correct it with the Latin Vulgate and LXX.

Nonetheless, as they made numerous text critical decisions where their data differed, they ended up creating a new Greek NT text, which they never printed or published. Thus, the precise Greek text behind the KJV had never existed anywhere at that point except in their own minds.

In 1881, during the official Revision of the KJV, the Revisers were asked to set out in the margins all the places where the Greek text resulting from their textual choices differed from the Greek text behind the KJV. But his was hard to do, first, because they ended up making more changes than they had planned, and second, because the Greek text of the KJV had never been printed before, as Scrivener noted in his preface.

Ironically, this means that the Greek text behind the KJV was only ever published because of the Revised Version, and it was created by the Revisers as a companion volume to the 1881 RV. Contrary to some of the slander sometimes raised against them, no one would even have a copy of the Greek text behind the KJV had it not been for the integrity of the Revisers of 1881 and their determination to fulfill their obligations. This text was reprinted again a half-dozen times. This text stands behind, for example, Strong’s Concordance of the Bible, (Strong himself worked on the Revision as well), and all other such tools that refer to the Greek text of the KJV NT. Scrivener explained in his preface (which can be read here) what this text was and where it came from. “The special design of this volume is to place clearly before the reader the variations from the Greek text represented by the Authorized Version of the New Testament which had been embodied in the Revised Version.” He continues,

The Cambridge Press has therefore judged it best to set the readings actually adopted by the Revisers at the foot of the page, and to keep the continuous text consistent throughout by making it so far as was possible uniformly representative of the Authorized Version. The publication of an edition formed on this plan appeared to be all the more desirable, inasmuch as the Authorized Version was not a translation of any one Greek text then in existence, and no Greek text intended to reproduce in any way the original of the Authorized Version has ever been printed. In considering what text had the best right to be regarded as ‘the text presumed to underlie the authorized Version,’ it was necessary to take into account the composite nature of the Authorized Version, as due to successive revisions of Tyndale’s translation.

F.H.A. Scrivener

He notes further; “It was manifestly necessary to accept only Greek authority, though in some places the Authorized Version corresponds but loosely with any form of the Greek original, while it follows exactly the Latin Vulgate.” That is, sometimes the KJV translators ignored all of the Greek data they had to instead follow the Latin Vulgate (the Latin Vulgate thus influenced the text of the KJV at numerous stages; its influence on the Byzantine manuscripts, Erasmus’ incorporation of numerous Vug. readings into his text, and the KJV translators’ additional incorporation of even more Latin Vulgate readings). Since Scrivener refused to “back-translate” the English into Greek where none of the Greek sources the translators used had that Greek reading, even the text of Scrivener is not exactly the text behind the KJV. No such text technically exists anywhere.

And it’s worth noting, no one has ever done for the OT what Scrivener did for the NT, and so the original language text of the KJV OT has never existed in print. They deviated from their edition of the Hebrew Masoretic text in hundreds of places. Their OT text disagrees with every Hebrew Manuscript in existence, and, “to this day, no printed edition of the Hebrew Bible contains the exact Hebrew words behind the English words of the King James Version of 1611″ (James Price, King James Onlyism, pg. 254).

Why Claims Of Perfection For The KJV Or The TR Don’t Work

Sadly, some folks like to dishonestly claim that this Greek text is identical to “thousands” of Greek manuscripts (it actually differs from every single Greek manuscript in existence that’s of sufficient size to contain any textual variants), and promote it as the verbally perfect “preserved” words of the inspired original. Obviously, the very preface to the work by its editor poses a problem for such a position. So one publisher thus published an edition of the 1881 Scrivener TR which omits his preface, which has become the standard Greek text in KJV Only and TR Only circles. This “preface-safely-omitted” edition was the text used at the Fundamentalist Bible College I graduated from, which claimed in its doctrinal statement that this text and the KJV it translates were “the very words God inspired” now providentially preserved for all English speakers. But as John Kohlenberger noted in his lecture at the SBL commemoration of the 400th anniversary of the KJV (Kohlenberger, John R. III. “The Textual Sources of the King James Bible.” In Translation That Openeth the Window: Reflections on the History and Legacy of the King James Bible, edited by David G. Burke, 43–53. SBL: Biblical Scholarship in North America 23. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2009), “It is safe to say that, given their resources, the KJV translators worked from an eclectic text. Certainly they did not exclusively follow any one text. Nor did they, as some noncritical writers claim, limit their choices to what could be found in the texts that would later be called the Textus Receptus (TR).” David Trobisch noted (Trobisch, David. “The KJV and the Development of Text Criticism.” In The King James Version at 400 Assessing Its Genius as Bible Translation and Its Literary Influence, edited by David G. Burke, John F. Kutsko, and Philip H. Towner, 227–34. Society of Biblical Literature, 2013) in a similar vein, “Obviously, the translators of the KJV had created their own eclectic Greek text, a text that followed neither a specific manuscript nor a specific printed edition.”

Anyone who wants to claim that this text is perfect is free to do so. But such a claim requires the belief that the KJV translators were inspired by God with new revelation in their text-critical decisions. And such a claim is incompatible with a claim that this same text is the “preserved” word of God (however commonly these two words are used together by some who refer to this text). To preserve means to keep something the same, not to make it different. The Greek text of the KJVNT didn’t exists until 1611, and didn’t exists in print until 1881. If it is the verbally perfect Greek text, then this demands that God didn’t finish giving his Word until 1611. This is why I ultimately abandoned the belief that the English translation of the KJV was perfect, which I was raised on, and then abandoned the belief that the Scrivener TR was perfect, which I had been taught in Bible College.

Every form of such a position demands the belief that the KJV translators were supernaturally moved by God with new revelation.

But I was compelled by the evidence rather to the position that God had preserved his Word – not magically re-inspired it in 1611. Thus, as I often put it, I left the Shire I had been raised in (or was kicked out of it – both are sort of true).

I sometimes compare TR Only positions to the Emperor’s New Clothes. Those who hold these positions “ooh and aah” about how their position is more intelligent than their cousins who believe God inspired the English of the KJV. But they too must believe that God inspired the KJV translators with new revelation, and some kid in the crowd is bound to point out that the Emperor is still naked.

Textual Criticism Improves Beyond The KJV

But the maturing of textual criticism didn’t stop with the data from the manuscripts which informed the printed Greek texts used by the KJV translators, and their textual decisions based on that data. In fact, the KJV translators made it quite clear that they wanted revision to continue. We kept discovering more, kept looking more closely at what we already had, and kept maturing the discipline as a result. A major step was made in 1675 when data from some 80 mss was published in a new Greek text by Bishop John Fell – the most ever compared at that time.

John Mill And The Fight – Certainty Against All Evidence? Or Confidence Based On Evidence?

1707 was a landslide moment in the discipline. John Mill published his landmark text in 1707 (see here), now collating data from 100 (or some say 80) mss. The data had grown more than a hundredfold. We were now aware of some 30,000 textual variants. This created quite a stir. In reaction to what felt like the loss of certainty about the text, conservatives like Pastor Daniel Whitby and some others essentially enshrined the 1550 Stephanus text, claimed it should never be altered, and refused to consider any new data that would correct it. And, as often happens, the fear-based reactions of hyper-conservatives against historical data provided the ammo for radical skeptics to attack the faith. Skeptic John Collins immediately stepped up, using the arguments of Whitby to claim that the Christian faith was now undermined. As Tregelles later explained;

And thus in 1713 Anthony Collins, in his ‘Discourse Of Free Thinking,’ was able to use the arguments of Whitby to some purpose, in defense of his own rejection of the authority of Scripture. This part of Collins book ought to be a warning to those who raise outcries on subjects of criticism. If Mill had not been blamed for his endeavors to state existing facts relative to the [manuscripts] of the Greek Testament, and if it had not been said that thirty thousand various readings are an alarming amount, this line of argument could not have been put into Collins’s hands.

– Tregelles, 1854, An Account Of The Printed Text Of The Greek New Testament, pg. 48.

But we had so many textual variants not because the text was suddenly less stable – but because we had so much more data. Meaning the text was that much more stable. Enter classicist Richard Bentley to the fray, who explained this in 1713 very well. He rightly saw the danger of both ditches; the rejection of all evidence in favor of unfounded certainty championed by Whitby, and the skepticism unconvinced by the evidence championed by Collins. He preferred instead a confidence based upon the evidence. “Bentley had to steer clear between two points, — between those who wished to represent the text of the NT as altogether uncertain because of the variations of copies, and those who used this fact of differences to depreciate critical inquiries, and to defend the text as commonly printed against all evidence whatsoever” (S. P. Tregelles, 1854, “An Account Of The Printed Text Of The Greek New Testament”). He pointed out that our faith was founded on historical evidence, and that Christian faith is always vindicated by historical data. “Depend on’t,” he said, “no truth, no matter of fact fairly laid open, can ever subvert true religion.”

If there had been but one manuscript of the Greek Testament, at the restoration of learning about two centuries ago, then we had had no various readings at all. And would the text be in a better condition then, than now we have 30,000? So far from that, that in the best single copy extant we should have had some hundreds of faults, and some omissions irreparable. Besides that the suspicions of fraud and foul play would have been increased immensely.

It is good therefore, you’ll allow, to have more anchors than one; and another MS to join with the first would give more authority, as well as security. Now choose that second where you will, there shall still be a thousand variations from the first; and yet half or more of the faults shall still remain in them both.

A third therefore, and so a fourth, and still on, are desirable, that by a joint and mutual help all the faults may be mended; some copy preserving the true reading in one place, and some in another. And yet the more copies you call to assistance, the more do the various readings multiply upon you; every copy having its peculiar slips, though in a principle passage or two it do singular service. And this is fact not only in the New Testament, but in all ancient books whatever.

’Tis a good providence and a great blessing, that so many manuscripts of the New Testament are still among us; some procured from Egypt, others from Asia, others found in the Western churches. For the very distance of places, as well as the numbers of books, demonstrate, that there could be no collusion, no altering nor interpolating one copy by another, nor all by any of them.

….where the copies of an author are numerous, though the various readings always increase in proportion, there the text, by an accurate collation of them made by skillful and judicious hands, is ever the more correct, and comes nearer to the true words of the author.

….And so it is with the Sacred Text: make your 30,000 as many more, if numbers of copies can ever reach that sum: all the better to a knowing and serious reader, who is thereby more richly furnished to select what he sees genuine. But even put them into the hands of a knave or a fool, and yet with the most sinistrous and absurd choice, he shall not extinguish the light of any one chapter, nor so disguise Christianity but that every feature of it will still be the same.

– Richard Bentley, 1713, Remarks Upon A Late Discourse of Free Thinking, Pg. 92-113.

Dean John Burgon went back to Bentley and his brilliant assessment of the textual situation a century later when he noted;

But I would especially remind my readers of Bentley’s golden precept, that, “The real text of the sacred writers does not now, since the originals have been so long lost, lie in any [manuscript] or edition, but is dispersed in them all.” This truth, which was evident to the powerful intellect of that great scholar, lies at the root of all sound textual criticism.

– John Burgon, 1896, The Traditional Text Of The Holy Gospels Vindicated And Established, pg. 26.

Moving Forward By Going Back To Erasmus

But both Bentley and Burgon were actually simply echoing the principles of textual criticism that had been laid out by Erasmus. Erasmus faced a great deal of opposition to his “updating” of the text in his own age, especially because he often claimed that the long-trusted Latin Vulgate needed to be updated. But he adamantly maintained that we should follow the historical data wherever it leads, and that this will never jeopardize the Christian faith. He, like Bentley, recognized that the demand for textual certainty even in the face of opposing evidence was based upon an ungrounded fear, and a weak view of the Christian faith;

Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam

Do you intend to overlook all this and follow your own copy, though it was perhaps corrupted by a scribe? For no one asserts that there is any falsehood in Holy Scripture (which you also have suggested), nor has the whole question on which Jerome came to grips with Augustine anything at all to do with the matter. But one thing the facts cry out, and it can be clear, as they say, even to a blind man, that often through the translator’s clumsiness or inattention the Greek has been wrongly rendered; often the true and genuine reading has been corrupted by ignorant scribes who are half-taught and half-asleep. Which man encourages falsehood more, he who corrects and restores these passages, or he who would rather see an error added than removed? For it is of the nature of textual corruption that one error should generate another. And the changes I make are usually such as affect the overtones rather than the sense itself; though often the overtones convey a great part of the meaning. But not seldom the text has gone astray entirely. And whenever this happens, where, I ask you, do Augustine and Ambrose and Hilary and Jerome take refuge if not in the Greek original?

…There are men who do not like to see a text corrected, for it may look as though there were something they did not know. It is they who try to stop me with their authority of imaginary synods; they who build up this great threat to the Christian faith; they who cry ‘the church is in danger’ (and no doubt support her with their own shoulders, which would be better employed in propping a dung-cart) and spread suchlike rumors among the ignorant and superstitious mob…I see nothing here that much affects the genuineness of the Christian faith. If it were essential to the faith, that would be all the more reason for working hard at it. Nor can there be any danger that everybody will forthwith abandon Christ if the news happens to get out that some passage has been found in Scripture which an ignorant or sleepy scribe has miscopied or some unknown translator has rendered inadequately.

– Erasmus, Letter to Dorp, EP 337, CWE 71.

It was clear by 1707 that the discipline needed an overhaul in light of the data growing by such margins. Erasmus’ principle of continuing to revise the text in light of ever-growing data needed to be applied again, and so it was. 1707 marks a major turning point, but so on the development went, through Tregellas, Tischendorf, Hort and Westcott, Scrivener, Burgon, Aland, etc., through the major shift made in the 26th edition of the Nestle-Aland text, all the way to the present NA 28 (or the RP 2005 preferred by some). Now, we have GA numbers for 5,874 Greek NT manuscripts (the current INTF count, though the actual number of manuscripts is slightly lower). That’s an astounding amount of data compared to the few dozen or so Greek NT manuscripts that loosely formed the basis for our earliest English translations.

But we keep discovering new relics. Several of what are now the oldest papyri manuscripts for a few books of the NT have just been published within the last year. And we keep looking more closely at what we already have. And we keep plotting textual relationships in increasingly sophisticated ways, as the newer data is incorporated. And thus we keep maturing the methods and principles of NTTC in light of all this ever growing knowledge. Of course, not all scholars see things the same way. There is sometimes vigorous debate about the methods of NTTC. But we undeniably have more data than at any prior point in history, and thus more confidence about the text. As Scrivener put it in his 19th century introduction to textual criticism;

[The Quality and abundance of the manuscripts of the NT] present us with a vast and almost inexhaustible supply of materials for tracing the history, and upholding (at least within certain limits) the purity of the sacred text: every copy, if used diligently and with judgment, will contribute somewhat to those ends. So far is the copiousness of our stores from causing doubt or perplexity to the genuine student of Holy Scripture, that it leads him to recognize the more fully its general integrity in the midsts of partial variation.

– F.H.A. Scrivener, 1861, A Plain Introduction To The Criticism Of The New Testament, pg. 4.

To put it into perspective, I often point out that when the KJV translators made their text-critical choices which created the text behind the KJV, they were working with only a small percentage of the Greek manuscript data we have available today. And they stood at what was really the infancy of developing NTTC methodology. These limitations notwithstanding, they still created an excellent translation that is sufficient as the Word of God, and still in use today. In fact, I often say that every single English-speaker should own a copy. (I don’t think anyone should only use a KJV). But the discipline has matured in massive ways since then. NTTC is still exactly the same *thing* it was in 1516. We are still doing today exactly what Erasmus was doing then. The “DNA” is identical, so to speak. It has just matured such that comparing them is somewhat like comparing a small child and that same child as a grown man. Same person; just much more mature.

And at each stage texts and translations of those texts were produced which evidence the hand of NTTC at that stage. Sadly, for the first several hundred years of textual criticism, the impact of the increasing knowledge upon English translations wasn’t as great as it should have been. There was early on a bit of a disconnect between NTTC and English translations. Fortunately, that’s not as much the case today. What’s really odd though is when some folks demand that we only use the KJV, the product of 16th-17th century NTTC. The eclectic Greek text behind the KJV was the result of exactly the same kind of NTTC as that which stands behind the NA 28. There is not a single Greek Manuscript which contains the exact Greek text that stands behind the KJV.

Not one.

Not even close.

Its eclectic text is undeniably the product of NTTC – it’s just based on far less data, and is a product of the science in its infancy. Yet some act as though all the various works of a mature Picasso should be forfeited in favor of a stick figure drawing he produced as a child.

The Stability Of The New Testament Text

But perhaps most astounding, and most important, is the realization of how strikingly similar the products of each age of NTTC are to one another. Take a 1526 Tyndale NT, the first English translation of the Greek NT (a beautiful photo-facsimile is available here) and hold it next to a 2016 ESV. Compare them carefully and the thing that should most strike you is how amazingly alike they are. It’s simply astounding how 500 years of growth in NTTC has made so little change to our NT text. Not because NTTC hasn’t grown and matured. Is surely has. But because the text of the NT really is that stable and trustworthy. The more data we compile, the more textual variants we discover. The count is now somewhere around 400,000. Though this must be kept in perspective. The vast majority of these textual variants (something more than 99% of them) relate to spelling changes that in no way impact the meaning of the text, or errors that are immediately obvious as such to anyone who can read. Exactly two of these textual variants relate to passages of Scripture that are 12 verses long. A few dozen more of these textual variants relate to 1-2 whole verses of biblical text. All of the remaining textual variants are smaller than a single verse, and concern phrases, a phrase, or, most often, a single word of the text. 500 or so of them are listed in Metzger’s textual commentary, and those essentially make up the whole of most textual discussion today. In an entire sea of confidence, these reflect only a few insignificant drops of uncertainty.

The significant textual variants in the NT manuscripts are like tiny drops in the sea of confidence which the transmission tradition gives us for the text of the New Testament.

The number and type of textual variants that exists don’t mean we are less confident of the wording of the original text. On the contrary, we are more sure of it than ever before. And it’s absolutely amazing how stable and trustworthy the transmission of the NT text is now found to have been through the millennia. Whatever minor discrepancies can be found in every manuscript, everyone who ever read any Greek NT manuscript (and anyone today who uses anygood translation of the text) still has possession of a trustworthy and sufficient copy of the Word of God, which still proclaims the same message, and the same doctrines. Given 2,000 years of transmission history under every conceivable condition, that reality is, I think, a clear mark of the providential concern of God to preserve the text.

What’s most astounding about the updates of textual criticism over 500 years is how amazingly little the printed text of our NT has needed altered. The NT text is simply amazingly stable.

But minor details continue to be tweaked. Thus, updates will continue to be required if scholars want to be accurate and careful with the exact words of the text. And those who respect Scripture as God’s Word should be especially concerned to give attention to every single word of the text.

The Scope Of Continued Updates

These updates are now typically incredibly minor compared to the “landmark” shifts of a few centuries ago. And barring some unforeseen astounding new discovery, will continue to be rather minor. Even the radical skeptic Bart Ehrman (who has risen to fame as North America’s most well-known skeptic because of the doubt he raises about the text of the New Testament), has admitted that the text of the New Testament is for all practical purpose rather settled at this point, and won’t likely ever receive another massive overhaul unless unforeseen extraordinary data comes to light. While he might express himself differently today, in a major scholarly publication in 2012, he acknowledged;

“Textual scholars have enjoyed reasonable success at establishing, to the best of their abilities, the original text of the New Testament. Indeed, barring extraordinary new discoveries or phenomenal alterations of method, it is virtually inconceivable that the character of our printed Greek New Testaments will ever change significantly.”

(The Text Of The New Testament In Contemporary Research, 2nd ed., pg. 825).

There’s simply not likely to be any rather radical changes. For example, the differences between the NA 27 and the NA 28 amounted to only 30+ changes to the actual text of the NT which it printed.

But of course, we could always assume, as a few have, quite vocally at times, that none of this is true, and that new updates are just a way to steal money out of your pockets. An odd (and perhaps slanderous) claim, given that the German Bible Society now makes the NA text freely available online. Giving something away free isn’t usually the best strategy for stealing money out of someone’s pockets.

Scholars continue to have slightly different opinions about how to put the data together. This is why rather than just one Greek text, there are several that are employed by different scholars of different stripes. Like the RP one here (which has gained little traction among scholars), the standard one here, or the relatively new one here. I would love to see good English translations made of each of these modern texts, which would then reflect better in English the kind of difference of opinion that modern textual critics sometimes have about the shape of the original text. Most English translations today are from the NA text. But in any case, minor updates will continue to be made to the text of the NT, for all of the reasons above. Not because we are trying to get further away from the original New Testament, but because we are trying to get closer and closer to the original wording of the original text, and the small gap between what they wrote and what we read gets increasingly smaller with every new generation.

These updates then are not a bad thing. They don’t undermine our faith in the NT. Rather, they simply make us all the more confident that we have the very word of God. They help us tweak our understanding of those words and our printing of them in the minor ways. And thus they help us print the original text of the New Testament with greater and greater precision and confidence.

The second line under the heading “Why Claims Of Perfection For The KJV Or The TR Don’t Work” contains the phrase “it actually differs from every single Geek manuscript in existence.”

Unless there is such a thing as a “Geek manuscript,” there would appear to be a typo here.

It’s also present in the version on bloggingtheword.com.

Still an enjoyable read, though.

Thanks! I think I fixed it. I appreciate you reading!

I am looking forward to your first post to the Facebook group, “King James Bible Calvinists”.

Hello Mr. Timothy Berg, I appreciate your article on Revelation 1.8. It seems to me that the error in the TR puts a nail in the coffin of confessional bibliology if the CB advocates are saying that the WCF at 1:8 is referring to the “TR(s)”. I haven’t heard anyone use your article in discussions of CB so I am wondering if I’m missing something. I appreciate you and Mark Ward and others who are trying to unite Christians by tearing down walls that have been put up to separate us. Blessings to you and your ministry.

“To claim at this point that any edition of the Textus Receptus is the verbally perfect Word of God, or to claim that the KJV is the only verbally perfect Word of God, is, at this point, to demand that the true text of the Bible was lost from the second century on until 1516, when God supernaturally moved Erasmus to make a mistake (without even the knowledge of Erasmus!) which would then restore the true text of the NT that had been lost.”