The Millenary Petition – Its Extant Sources

In our last post, we surveyed the political and religious climate at the coming of King James I to the English throne, and the discontent that led to the presentation to him of the Millenary Petition, properly titled, The Humble Petition of Ministers of the Church of England, Desiring Reformation of Certain Ceremonies and Abuses of the Church. It remains to examine the text of the Petition itself, which we present briefly here, and to explain the requests it made and their impact, which we may do in later posts.

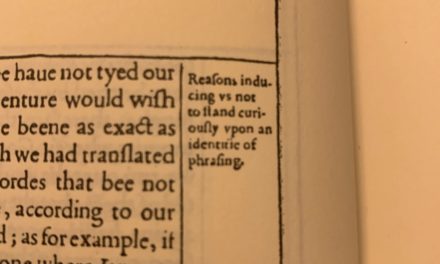

I first came across a copy of the Petition in the source-book of Kenyon (after having ceased looking for it when one misinformed author I read claimed that no extant copy remained). Kenyon cites Thomas Fuller’s The Church History Of Britain, 1648, (reprint of 1837, Vol. III, pg. 193-195) as his source. Roland Greene Usher, in his, The Reconstruction of the English Church, 1910, Vol. I (pg. 290, note 1) noted three different manuscripts of the Petition extant today, variously dated; Add. MSS. 8978 (fol. 107), Add. MSS. 28571 (fol. 175), and, MSS Stowe 180, (fol. 7). None of these is likely to be the original, which no longer remains. (The Wikipedia article on the Petition mistakenly links to an unrelated later petition to Bishop Laud as the original). The form found in Fuller is the most commonly printed. A selectively abbreviated form can also be found in Strype’s, The Life and Acts of John Whitgift. Fuller notes that it likely first occurred in print (as opposed to its manuscript form) when it was printed with the Answer given to it by the Universities in 1603.

I first came across a copy of the Petition in the source-book of Kenyon (after having ceased looking for it when one misinformed author I read claimed that no extant copy remained). Kenyon cites Thomas Fuller’s The Church History Of Britain, 1648, (reprint of 1837, Vol. III, pg. 193-195) as his source. Roland Greene Usher, in his, The Reconstruction of the English Church, 1910, Vol. I (pg. 290, note 1) noted three different manuscripts of the Petition extant today, variously dated; Add. MSS. 8978 (fol. 107), Add. MSS. 28571 (fol. 175), and, MSS Stowe 180, (fol. 7). None of these is likely to be the original, which no longer remains. (The Wikipedia article on the Petition mistakenly links to an unrelated later petition to Bishop Laud as the original). The form found in Fuller is the most commonly printed. A selectively abbreviated form can also be found in Strype’s, The Life and Acts of John Whitgift. Fuller notes that it likely first occurred in print (as opposed to its manuscript form) when it was printed with the Answer given to it by the Universities in 1603.

The standard academic printing is probably now the form in the volume of canons edited by Gerald Bray (pg. 817-819). It is divided by him into smaller enumerated sections which makes it easier to cite each individual petition. The volume is expensive. I reproduce below for later reference the form in Kenyon, whatever differences it may bear from the extant manuscripts or other printings. It is not a critical edition, but is probably the most easily accessible source. (Read the section free at Google Books here).

The Millenary Petition – Its Text

______________________

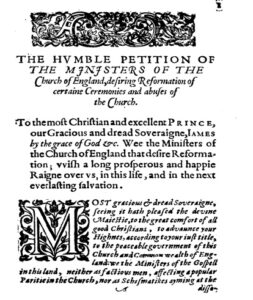

The humble petition of ministers of the Church of England, desiring reformation of certain ceremonies and abuses of the Church.

To the most Christian and excellent prince, our gracious and dread sovereign, James, by the grace of God, [etc.], We, the ministers of the Church of England that desire reformation, wish a long, prosperous and happy reign over us in this life, and in the next everlasting salvation.

Most gracious and dread sovereign, seeing it hath pleased the Divine Majesty, to the great comfort of all good Christians, to advance your Highness according to your just title, to the peaceable government of this Church and Commonwealth of England; we the ministers of the gospel in this land, neither as factious men affecting a popular parity in the Church, nor as schismatics aiming at the dissolution of the state ecclesiastical; but as the faithful servants of Christ, and loyal subjects of your Majesty, desiring and longing for the redress of divers abuses of the Church, could do no less, in our obedience to God, service to your Majesty, love to his Church, than acquaint your princely Majesty with our particular griefs. For, as your princely pen writeth: ‘The king, as a good physician, must first know what peccant humours his patient naturally is most subject unto, before he can begin his cure.’ And, although divers of us that sue for reformation have formerly, in respect of the times, subscribed to the [Prayer] Book, some upon protestation, some upon exposition given them, some with condition[s], rather than the Church should have been deprived of their labour and ministry; yet now we, to the number of more than a thousand, of your Majesty’s subjects and ministers, all groaning as under a common burden of human rites and ceremonies, do with one joint consent, humble ourselves at your Majesty’s feet to be eased and relieved in this behalf. Our humble suit, then, unto your Majesty is, that [of] these offences following, some may be removed, some amended, some qualified:

I. In the church service. That the cross in baptism, interrogatories ministered to infants, confirmation, as superfluous, may be taken away: baptism not to be ministered by women, and so explained: the cap and surplice not urged: that examination may go before the communion: that it be ministered with a sermon; that divers terms of priests and absolution, and some other used, with the ring in marriage, and other such like in the Book, may be corrected: the longsomeness of service abridged: church-songs and music moderated to better edification: that the Lord’s day be not profaned, the rest upon holy-days not so strictly urged: that there may be a uniformity of doctrine prescribed: no popish opinion to be any more taught or defended: no ministers charged to teach their people to bow at the name of Jesus: that the canonical scripture only be read in the church.

II. Concerning church ministers. That none hereafter be admitted into the ministry but able and sufficient men; and those to preach diligently, and especially upon Lord’s day: that such as be already entered, and cannot preach, may either be removed, and some charitable course taken with them for their relief; or else be forced, according to the value of their livings, to maintain preachers: that non-residency be not permitted: that King Edward’s statute for the lawfulness of ministers’ marriage be revived: that ministers be not urged to subscribe but according to the law to the Articles of Religion, and the King’s Supremacy only.

III. For church-livings and maintenance. That bishops leave their commendams; some holding prebends, some parsonages, some vicarages with their bishoprics: that double-beneficed men be not suffered to hold some two, some three, benefices with cure, and some two, three, or four dignities besides: that impropriations annexed to bishoprics and colleges be demised only to the preachers-incumbents, for the old rent: that the impropriations of layman’s fees may be charged with a sixth or seventh part of the worth, to the maintenance of the preaching minister.

IV. For church-discipline. That the discipline and excommunication may be administered according to Christ’s own institution; or, at the least, that enormities may be redressed: as, namely, that excommunication come not forth under the name of lay persons, chancellors, officials, &c.: that men be not excommunicated for trifIes, and twelve-penny matters: that none be excommunicated without consent of his pastor: that the officers be not suffered to extort unreasonable fees: that none having jurisdiction, or registers’ places, put out the same to farm: that divers popish canons (as for restraint of marriage at certain times) be reversed: that the longsomenes of suits in ecclesiastical courts, which hang sometimes two, three, four, five, six, or seven years, may be restrained: that the oath ex officio, whereby men are forced to accuse themselves, be more sparingly used: that licences for marriage, without banns asked, be more cautiously granted.

These, with such other abuses yet remaining, and practised in the Church of England, we are able to show not to be agreeable to the scriptures, if it shall please your Highness further to hear us, or more at large by writing to be informed, or by conference among the learned to be resolved. And yet we doubt not but that, without any farther process, your Majesty, of whose Christian judgment we have received so good a taste already, is able of yourself to judge the equity of this cause. God, we trust, hath appointed your Highness our physician to heal these diseases. And we say with Mordecai to Esther, ‘Who knoweth, whether you are come to the kingdom for such a time ?’ Thus your Majesty shall do that which, we are persuaded, shall be acceptable to God; honourable to your Majesty in all succeeding ages; profitable to his Church, which shall be thereby increased; comfortable to your ministers, who shall be no more suspended, silenced, disgraced, imprisoned, for men`s traditions; and prejudicial to none, but to those that seek their own quiet, credit and profit in the world. Thus, with all dutiful submission, referring ourselves to your Majesty’s pleasure for your gracious answer, as God shall direct you; we most humbly recommend your Highness to the Divine Majesty; whom we beseech for Christ’s sake to dispose your royal heart to do herein what shall be to his glory, the good of his Church, and your endless comfort.

Your Majesty`s most humble subjects, the ministers of the gospel, that desire not a disorderly innovation, but a due and godly reformation.

– J. P. Kenyon, The Stuart Constitution, 1603-1688: Documents and Commentary, 2nd ed., (Cambridge University Press, 1986), 117–19.

_____________

The Millenary Petition – Its Impact

The various requests made in the Petition provide a window into the past; a snapshot, frozen in time, of the tensions and uncertainties, hopes and fears, that were present when James I took the throne in 1603. They thus form essential background to the Hampton Court Conference where these hopes would rise to their highest point, before being largely dashed. That Conference in turn provides essential background to the King James Bible and its birth.

But how closely connected is the Petition to the Conference? Did the Conference flow out of the Petition as its result? The common answer has always been, “Yes, of course.” Strype for example concluded (or affirmed the consensus) that, “Hence it is evident that this petition gave the occasion to the King to appoint the conference…” One scholar, taking a quite contrary line, has recently answered, “No, not that we can tell.” Thus, in our next post we will examine the impact of the Petition and its connection to the Hampton Court Conference, and ask whether the consensus about their close connection should be challenged.

Comments