In circles that defend the KJV as the preserved Word of God for the English speaking people, one occasionally sees claims that modern translations have “deleted” Acts 8:37 from the Bible. Ironically, the KJV is often claimed to be a “Baptist” Bible. It is sometimes then claimed that modern translations have removed the verse (hereafter vs.) to appease “the Vatican” or “baby sprinklers,” and to “remove Believer’s Baptism from the Bible,” (since without vs. 37 no confession of faith is explicitly required of the eunuch). Similar accusations abound (like here, here, here, and scores of other places). I won’t address a defense of Believer’s Baptism here. I have good and godly friends on both sides of that question. For most who defend the KJV, it can be assumed as a given. But what of such accusations?

R. B. Ouellette’s A More Sure Word is a more careful work. He avoids the egregious errors of many such accusations, a fact for which I am grateful. But Acts 8:37 in modern translations is still used as an example of, casting “doubt” on the “availability of Scripture.” He envisions a situation like this;

Another problem of doubt that stems from the use of modern Bibles is the doubt cast upon the availability of Scriptures. Imagine that you are in a church setting. The preacher, who is reading from a King James Bible, says to turn in your Bible to Acts 8:37. Imagine you are trying to follow along with him in a New American Standard Bible. Finally, you are able to find the passage. This particular vs. is relegated to a footnote at the bottom of the page and is not in the text…These are just a few of the scores of verses that are missing from the Critical Text, and subsequently from the translations that descend from it. When a layman reads statements like, ‘This verse is not found in the best manuscripts,’ doubt is placed in his mind as to the availability of Scripture. Also, the question of these being the ‘best’ manuscripts is a biased statement that is highly in question by those who study the facts.

(pg. 59-60)

Most modern translations do contain the vs., but in a footnote (as Ouellette’s story admits) due to its dubious textual support [1]. But is placing the vs. in a footnote like this really, “casting doubt upon the availability of Scripture,” as Ouellette alleges? Or is it just being honest with the data? He takes issue with a claim that Acts 8:37 (hereafter Ac.8:37) is not found in “the best” manuscripts (though see the ESV’s footnote to vs. 36, which is actually far more graciously worded). I have no doubt his objections come from a sincere heart. But the truth is, this vs. is not found in the majority of manuscripts (hereafter abbreviated MSS.). It’s not in the Byzantine MSS. [2]. It’s not present in any of the earliest MSS. In those that do have it, it’s sometimes only in the margin as a marginal comment. Further, its not in any of the MSS. that Ouellette himself would in other places identify as most important.

I set out the external evidence for the textual variant in Ac.8:37 in a chart, using standard abbreviations, and data from standard apparatuses. [4] The numbers in the “Greek” columns are standard GA numbers by which we refer to the Greek MSS. of the NT. (Don’t be scared of the word “Greek” – all actual Greek and Latin text will be restricted to the endnotes for this blog post. You’re Welcome.) Each number stands for one of our Greek MSS. of the NT. The other two columns represent its presence or absence in ancient translations of the NT (Vers.) and quotations of the NT by ancient writers (Pat.), which serve as secondary witnesses to the form of the text.

Note that the chart is divided into two basic parts; on the left side is evidence for the shorter reading, where the text goes straight from what we call vs. 36 to what we call vs. 38, not containing what we call vs. 37. But note that NT verse divisions didn’t exist until 1551 when Stephanus put them in his text, thus its not a matter of these MSS., “taking out a verse,” but rather of having a shorter as opposed to a longer form of the text.

On the right side of the chart is the evidence for the longer reading (including what we now call vs. 37). I have further divided this section into two parts, for a simple reason. Technically, instead of two sections, the chart should have 22 different sections examining the 22 different forms that Acts 8:36-38 is found in. But few would claim that vs. 37 is authentic, but that the KJV form of it is in error. So usually, there are only two forms of the text being defended – the KJV form, and anything that is not like the KJV form. While there is a variety of evidence that has some form of vs. 37 in the text, I have divided this evidence into that which supports the KJV/TR form, and that which would suggest that the KJV/TR is in error, or is too partial to be used to support the full TR form. See the details of the chart in the Excel file here.

The Greek Evidence For / Against The Verse

We have today some 5,874 extant Greek NT MSS. (counting the INTF’s official GA numbers – the actual number of MSS., when duplicates etc. are accounted for, is slightly lower). Most of them do not contain the entire NT. About 660 MSS. contain all or parts of the Book of Acts. Ac.8:37 is found today in only 64 of the later extant Greek MSS. of the book of Acts. With many variations, it is found in the text of;

It is also found in a variety of different forms in the margins of minuscules 88, 221, 429, 452, 628, 1877, 1892, 2544, and 2816. Further, of these MSS. that do have it, it occurs in a total of 12 different basic forms, with a variety of minor variations between witnesses to each form. If minor differences like a single word count as a different form, then there are 22 distinct forms. [5]

The entire vs. is completely absent from the majority of extant MSS. of Acts. [6] More important to most textual critics (with some exceptions), the vs. is absent from the oldest MSS. (see the upper left corner of the chart) that are generally considered most important. Of the 660 MSS. of the Book of Acts extant, (minus those that don’t contain this section of Acts) the vs. is absent from;

Understand – the number of Greek New Testament manuscripts that contain the exact wording of the Textus Receptus of Acts 8:37 is precisely one.

Incidentally, passages like this one (and hundreds of others we could look at) reveal that when someone claims that the KJV is based on “the majority of manuscripts,” or that “the majority of manuscripts support the KJV,” they are, quite simply, either ignorant, or dishonest. The number of Greek New Testament MSS. that contain the exact reading of the Textus Receptus of Ac.8:37 is exactly 1 – minuscule 1883 – dating from the 16th century. One doesn’t have to count well to see that “1” is not a “Majority” of 660.

Much more could be said about secondary evidence in the chart for/against authenticity. It’s not my goal here to argue that issue. You can see a slideshow of my arguments for why it is not authentic here. There is some very early patristic support for some form of the passage (that is, places where church Fathers quote the text), in Irenaeus and Cyprian. James Snapp is one of very few textual critics who advocates for the verse today, primarily on the basis of the patristic evidence. His argument is cogent. He technically defends a form of the text different than that found in the TR, and thus would still conclude that the KJV is in error, as I understand him.

When I share the textual data with those defending the KJV, they universally defend the KJV reading. The evidence is, they say, clearly convincing in favor of the KJV. Usually, seeing the chart above, they tell me that it is Cyprian and Irenaeus that they find so compelling. Interestingly, in most passages they find the reading of the majority of MSS. compelling enough to ignore all data that opposes it, but in this case they find the text of these two solitary Fathers weighty enough to overturn the reading of the vast majority of both early and late manuscripts. The problem with such a procedure is that they don’t find Irenaeus or Cyprian to be such weighty witnesses anywhere else in their text.

In fact, ironically, in exactly every single place that Irenaeus or Cyprian disagrees with the KJV, they find them untrustworthy. And even when they both agree together, but against the KJV, their witness is suddenly suspect. For example, in Acts 4:12, the KJV reads, “Neither is there salvation in any other: for there is none other name under heaven given among men, whereby we must be saved.” But both the Latin text of Irenaeus, and the text of Cyprian (according to the UBS 5 apparatus), in unity, omit the first clause, and only read, “For there is none other name under heaven given among men, whereby we must be saved.” Here, just a few chapters before these twin writers become unimpeachable in Ac.8:37, every KJV defender would conclude that these two Fathers cannot be trusted, even when they speak in unity, and that the majority of Greek MSS. (which agrees here with the KJV) is clearly most important.

One could be forgiven for suspecting that it isn’t the weight of these two Fathers that actually compels their defense of Acts 8:37, but a willingness to champion exclusively whatever evidence supports the KJV. Whether they realize it or not, this suggests that the KJV itself is really the only textual evidence that counts, and that other witnesses will be championed, or ignored, based solely on whether they agree or disagree with the KJV.

How The Verse Was Added To The KJV

It might be quite instructive to see how the vs. got into the KJV. The 1611 KJV did not translate directly from Greek manuscripts. The 1611 KJV is a revision of the 1602 Bishop’s Bible, which is one of a number of revisions of Tyndale’s 1534 NT, which had translated the 1522 edition of the Greek/Latin diglot of Erasmus of Rotterdam, first printed in 1516.

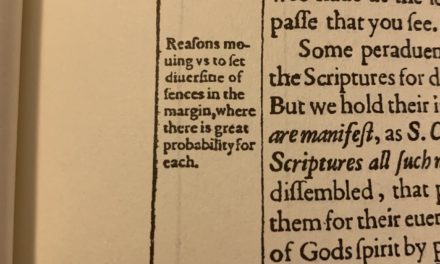

The KJV of course doesn’t always follow the Erasmus text. It is an eclectic combination of readings from different texts. But the KJV form of the text here comes from the Greek/Latin text of Erasmus printed in 1516. By contrast, the Compultensian Polyglot printed in 1514 did not include the vs., [7] as it was not in the commonly used Greek manuscripts. Thus, in terms of the history of printedGreek texts, there is a longer history of not including it than there is of including it (which makes claims about it being the “preserved” reading all the more odd). Here’s Erasmus’ 1516 text, the first Printed Greek text to add the vs. to the text, Erasmus 1516 Text of Acts 8:37 (Click links for image). Here’s his annotation explaining with the text in 1516 that he didn’t know of any Greek MSS. which had it in the text, 1516 Erasmus Annotation. He notes that the vs. (consisting of two sections) “is not found in the Greek Manuscripts,” [8] but he thinks that the Greek scribes have accidentally left it out (since it is in the Latin Vulgate he is using as a base), and so he suggests, “However, I think the omission was the result of negligent scribes.” [9] He then notes, “On the other hand I did find the reading in a certain Greek Manuscript, but only in the margin.” [10] He additionally notes in his later editions (in response to criticism by Stunica and Lee) [11] that it’s not found in Chrysostom, and not in the Spanish edition, though it was added to the Aldine edition (which he does not realize is in fact simply his own 1519 Greek text reprinted by others). However, it was in the copy of the Latin Vulgate that Erasmus had. We even know the exact form of the Vulgate Erasmus used, since he printed it alongside his own Latin translation and Greek text in his 1527 edition. [12] In his edition of the Greek/Latin text of Erasmus for Acts, Brown notes of the vs.,

Erasmus did not find this verse in his [codex] 1 or 2815, but derived the wording [13] from the margin of [codex] 2816: see [his annotation], where he suggests that it was originally omitted by scribal error… Consequently, he inserted a caret mark at the end of vs. 36 in [codex] 2815, accompanied by a symbol in the margin, to indicate that an addition was required. The subject was further discussed in his [letter to Lee] LB IX, 207 CE. [14]

Thus, Erasmus added it to his Greek text, not on the basis of a single Greek manuscript (none of the ones he had access to had it in the text), but on the basis of its presence in the Latin Vulgate, which he felt was vindicated by its presence in the marginal note of a single Greek manuscript, (Minuscule 2816). The manuscript that Erasmus had which has the text in the margin is viewable here;

Note the absence of vs. 37 from the text, and its presence in the margin. Erasmus made a rather premature judgment that its omission in the few Greek MSS. that he had access to was an accidental scribal error. He should be forgiven for such a judgment, as he was working with less than 1% of the amount of manuscript evidence we have available today.

When Lee criticized him for including the vs. here, because it wasn’t the reading of the Greek manuscripts, Erasmus responded;

Here Lee inveighs against the Greek manuscripts for no reason whatsoever. I had pointed out that in some Greek manuscripts one or two lines are lacking, but I also state that in my opinion they were omitted by the carelessness of scribes and I added them [adieci] because I had found them written in the margin in another codex. What is Lee’s complaint here? Nothing is missing, not even in the first edition.

In other words, from his very first edition he gave both readings through the use of the annotation, so how can Lee complain? One or the other reading is surely right. This is the basic point of using marginal notes – to make sure the reader has the right reading either in the text or note. He continues,

My annotation attests that some codices were defective, but that another came to the rescue. Is the fact that a corrupt passage is found in one or two manuscripts reason enough for not putting our trust in Greek manuscripts? Who would be so stupid as to trust one single codex in this kind of business? I am speaking as if it were an established fact that the Greek manuscripts are defective here. Yet the Greek exegete Chrysostom does not touch on the passage I have indicated is missing. I had published two editions before his commentaries provided me with support in preparing the third. But in the conclusion of this annotation Lee is more civil than he usually is in other passages. He says we must not trust Greek manuscripts unless we find that Jerome or one of the other old exegetes agrees with them. But that is the method I use in this whole work.

Erasmus often ignores the Greek MSS. on the basis of the Latin Vulgate or Patristic citations alone in constructing his text. He does this throughout his whole New Testament. He actually thinks it’s silly to demand that one follow only the Greek manuscripts. With one caveat: if the oldest copies of the Latin Vulgate agree with the readings of the Greek manuscripts, that combination is his most certain witness that the reading is correct. [16]

However, when Erasmus added the vs. to his text, since he added it in the form found in his copy of the late Latin Vulgate, not from the marginal note in 2816, he actually created a form of the text almost unknown in Greek. [18] This is the form that then became transmitted in the various editions of the TR, and then translated into the KJV. But as we saw above, this actual form of the text has only ever been found in 1 Greek manuscript, from the late 16th century, minuscule 1883 (and if one were technical about “every jot and tittle,” like the movable ν, then even 1883 differs from the TR form, which is then entirely unrepresented in any Greek manuscript). It does have some early support from Patristic citations and from some of the ancient versions (some Latin manuscripts, for example, as well as the later Armenian and Georgian versions), but the KJV/TR form of the vs. is not now and never was, so far as we can see from extant evidence, the common reading of the Greek manuscripts.

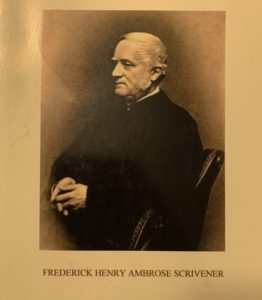

F. H. A. Scrivener (the man who edited the first printing of the Greek text behind the KJV in 1881) suggested long ago that it was likely simply a marginal explanatory note that was accidentally inserted into the text. He noted that often marginal notes could accidentally move into the text, like in I John 5:7. He explains;

A shorter passage or mere clause, whether inserted or not in our printed books, may have appeared originally in the form of a marginal note, and from the margin have crept into the text, through the wrong judgment or mere oversight of the scribe. Such we have reason to think is the history of 1 John v. 7, the verse relating to the Three Heavenly Witnesses, once so earnestly maintained, but now generally given up as spurious. Thus too Acts viii. 37 may have been derived from some Church Ordinal… [19]

Whether it is or isn’t original is not so much the point here. My point is that it is not a majority text reading, and that one should be consistent in invoking evidence. Further, one should be especially careful, when selectively presenting only evidence that favors one position, about making accusations. And even more, one should be careful of accusing someone of trying to “delete” a passage, when the accused are actually simply trying to present the evidence honestly. Moses required 2 or 3 witnesses to establish an accusation (Deut. 19:15), and there is wisdom in such a practice.

Baptismal Regeneration In The KJV

Erasmus The Roman Catholic – Editing The Greek Text To Affirm Infant Baptism

Erasmus Against Anabaptistism

Perhaps more pertinent to such accusations is a separate issue altogether; that of the duplicitous nature of such an claim. The notion that modern versions remove Ac.8:37 in order to remove Believer’s Baptism from the Bible is nothing short of absurd, and, frankly, has things backwards. Erasmus, the editor of the Greek text that essentially (though not exactly) lies behind the KJV, was a Roman Catholic Priest who believed firmly in Infant Baptism. His 1516 Greek text was dedicated to Pope Leo X, and when the Pope responded with a letter of commendation to Erasmus, he printed the Pope’s letter at the front of his 1519 and all subsequent editions (see letter here, or a snippet on the left – it is translated in CWE 3).

That Erasmus as a Roman Catholic Priest affirmed infant baptism should go without saying. But there are absurd claims that Erasmus “basically became a Baptist” floating around. For example, in Sorenson’s “Touch Not The Unclean Thing,” (pg. 191-193, the entire relevant section of which is absent a single primary source), the author claims that what Erasmus taught concerning baptism, “…is perilously close to, if not synonymous with, Fundamental Baptist theology. It certainly was Anabaptist doctrine.”) Thus, it should perhaps be demonstrated.

Erasmus himself argues against the Anabaptist practice of adult baptism in his commentary on Psalms 83. He asks, “Who is the evil genius who bewitches the wretched Anabaptists?” He goes on to explain that infant baptism stems from the Apostles. His argument is that Paul’s baptism of three families, (Crispus, Gaius, Stephanus, I Cor. 1:16; 16:15) and the Philippian Jailor and his whole family (Acts 16:32-24), plus Peter’s baptism of Cornelius and his whole household (Acts 10:24-48), surely included baptizing infants, since, “these families were likely to have a child or even several children.” [20] In a letter printed in his 1527 edition of the NT, Erasmus explained,

Above all we attest and desire that it be everywhere attested that we have never wished to detach ourselves by a finger or by a finger-nail from the judgment of the Catholic Church. If by any chance anything implying the opposite should be found, it was not said on purpose but involuntarily – for we are only human, and we wish that it should be considered retracted.

[21]

While Erasmus was more amenable to some Reformation thought than most Catholics of his day, he remained a committed, ordained, Roman Catholic priest up to the day of his death.

Erasmus Editing The Text

Further, Erasmus sometimes altered the text in support of his theology of baptismal regeneration and infant baptism. In I Pet. 2:2, Erasmus had to make a textual decision about the form of the text. The words, “into salvation” occur at the end of vs. 2 in some manuscripts, while they are absent in others. Erasmus of course only had a few MSS. of I Peter. The Vulgate had the additional words, as did 2816 which Erasmus had. But Erasmus’ text does not include them. He sided rather with Codex 1 and 2815 in omitting these words. One can see the absence of the words reflected in the KJV, “that ye may grow thereby,” and the ESV, “that by it you may grow up into salvation.”

Our concern here is Erasmus’ motive, not exegesis. He explains that he removed these last two words, despite their place in the Vulgate, partly because he felt that these two words would suggest that salvation was only possible for those who had gone on to maturity, which would preclude the salvation of infants by baptism. Erasmus believed that the baptism of infants granted them salvation. He argues that if the text has Peter connecting, “growing” with “into salvation,” then Peter would be suggesting that salvation is not possible for infants, but only for those who have gone on to maturity. He thus removes the words (see his annotation explaining here). The editor of the ASD volume explains, “…he argues against the additional words, partly on the grounds that ‘infants’ may receive salvation even before they have grown into spiritual maturity.” [20] Here is a Roman Catholic Priest making a textual decision and altering the words of the Greek text that came to inform the KJV, in order to make it conform to his practice of infant baptism and his theology of baptismal regeneration.

Here is a Roman Catholic Priest altering the words of the Greek text that would undergird the KJV to make it conform to his practice and doctrine of infant baptism.

The Anglican KJV Translators – Translating The KJV To Affirm Infant Baptism

Every one of the KJV translators was an Anglican (almost every one of them were Anglican priests), who all affirmed as their statement of faith “The 39 Articles” of the Church of England, which practiced infant sprinkling. That statement of faith, as worded in that age, had responded against the Anabaptists of the day in two points; first, in Article 38, in rejecting the communal living the Anabaptists urged, and second, in Article 27, in affirming the infant baptism which the Anabaptists had rejected. Here are those statements;

Article XXXVIII – The Riches and Goods of Christians are not common, as touching the right, title, and possession of the same; as certain Anabaptists do falsely boast. Notwithstanding, every man ought, of such things as he possesseth, liberally to give alms to the poor, according to his ability.

—-

Article XXVII – Baptism is not only a sign of profession, and mark of difference, whereby Christian men are discerned from others that be not christened, but it is also a sign of Regeneration or New-Birth, whereby, as by an instrument, they that receive Baptism rightly are grafted into the Church; the promises of the forgiveness of sin, and of our adoption to be the sons of God by the Holy Ghost, are visibly signed and sealed, Faith is confirmed, and Grace increased by virtue of prayer unto God. The Baptism of young Children is in any wise to be retained in the Church, as most agreeable with the institution of Christ.

[Emphasis mine.]

Puritan translations had often departed from the traditional ecclesiastical language of the Catholic Church, like “baptism” which had long had connotations of Infant baptism. They preferred translations like “washings” or “immersions,” which signaled adult immersion, not infant sprinkling. Instead of, “Church” which had long had connotations of in institutional gathering only legitimized by a representative of the Pope, they preferred, “congregation.” But the KJV translators believed in infant sprinkling, and wanted this tradition retained. As they wrote in their preface (penned by Miles Smith), The Translators To The Reader,

Lastly, we have on the one side avoided the scrupulosity of the Puritans, who leave the old Ecclesiastical words, and betake them to other, as when they put washing for Baptism, and Congregation in stead of Church…

In this they are following the rules set out by Archbishop Bancroft, whom King James had appointed over the translation work. His third rule specifically stated, “The old ecclesiastic words to be kept, viz,: as the word ‘Church’ not to be translated congregation etc.” The Anglican Church still practices infant baptism by sprinkling, and the KJV translators intentionally made sure that the KJV would support this view. Every time one reads “baptism” in the KJV instead of “immersion,” they do so because the KJV translators specifically didn’t want their translation to endorse Believer’s Baptism by immersion.

Every time you read ‘baptism’ in the KJV instead of ‘immersion,’ it is because the KJV translators specifically didn’t want their work to endorse Believer’s Baptism by immersion.

KJV Translator Lancelot Andrews

For example, KJV translator Lancelot Andrews explained,

But all the faithful have one beginning in the fountain of regeneration, that is in baptisme, and are all nourished with one nourishment; for they are all baptized into one body by one spirit, and all made to drink of one spirit; therefore they are all one body, and consequently should live in unity one with another.

He further explains that only those who have come into the mystical, universal Body of Christ, can be saved, “So that if a man be out of the body, and be not a member of Christ’s body, he cannot be saved and so Christ himself tells us…” [22] and that this entrance is through Water Baptism and the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper, without which a man cannot be saved. Scores of other such references can be found in his works.

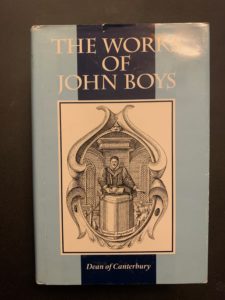

KJV Translator John Bois – Editing The KJV To Affirm Infant Baptism

In His Practice

John Bois was one of the KJV translators. If you hear people talk about “child prodigies” working on the KJV who knew Greek and Hebrew as children, it is likely Bois they are talking about. His linguistic skills were the stuff of legends. His good friend, Anthony Walker, wrote a brief biography of his life. In showing the love Bois had for those in his congregation, he records an interesting story about a woman in John’s congregation. They could not locate the record of baptism from her infancy, since she came to the church as an older child. This distressed Bois to no end. Thus, he entreated the church, for decades, to be able to baptize her to make sure of her salvation (and to make her finally able to receive the Eucharist as a believer). They continued to refuse, concluding that she was too old for baptism. But John’s constant fight for her soul eventually won the day (Life of John Bois, vi-4).

In His Preaching

Bois of course defended baptismal regeneration against the Anabaptists of his day who disagreed. He preached regularly, and staunchly, against the Anabaptists (following quotes from, “The Works of John Boys”), calling their ideas, “the factious interpretations of schismatics…all which equal their own fantasies with the scripture’s authority” (pg. 146), and denouncing their anarchy (pg. 266-67), and their “heresy.” These “brethren of separation, as they betray in their name [rejecting baptism of infants], so manifest in their nature, that they want [lack] exceedingly love…howsoever they seem to be of ‘the household of faith,’ it is not likely that they be of the ‘family of love.” (pg. 541.)

As Christ was crucified between two criminals, so, too, “the church is crucified between two malefactors: on the right hand schismatics, on the left papists: the one do untie the bonds of peace; the other do undo the unity of the Spirit” (pg. 735). The Ark is not Christ, but the Church, and only those baptized into it are saved (pg. 274-75).

When preaching on the story of Nicodemus in John 3, he explained, “Except a man be born of water] Some few modern Divines have conceited that these words are not to be construed of external baptism…” He explains that they are mistaken, finally concluding,

that all the Ancients have construed this text, as our Church does, of external baptism….By Baptism then a man is made a member of Christ, a childe of God, and an inheritor of the kingdom of Heaven: as our Church out of this place teacheth…as the spirit is an inward necessary cause, so the water is an outward necessary means of our regeneration…in this sense the Scripture terms baptism a bath of regeneration, whereby God cleanseth His Church, unto a remission of sins…

He notes that “..the Spirit in this new birth is instead of a father; the water instead of a mother; in this sense the Scripture terms baptism a bath of regeneration, Tit. iii.5, whereby God cleanseth his Church unto remission of sins…” and urges that, “If thou canst get baptism for thy child, despise not this blessed sacrament, for although it be not an immediate cause, yet it is a mediate channel of grace, whereby the mercies of God in Christ are conveyed unto us…” He goes on to explain that, “Baptism is therefore, in this chapter, put before faith; because it must always be before it…” (pg. 562).

He further explains in his sermon on Rom. 6:3 that initially this was done by immersion, but that now, “the minister at his discretion, according to the temper of the whether, and the strength of the child, might either dip it in the water, or pour water upon it. For charity and necessity may dispense with ceremonies, and mitigate the rigor of them in equity” (pg. 629). In preaching on the faith of the Canaanite Woman in Matt. 15, he notes that her faith brought salvation to her child, who hadn’t exercised faith, and allegorizes this to infant baptism, “Christ healed the child through the faith and invocation of the mother…Let no man doubt then but that the prayer and faith of our common mother availeth much in catechizing and baptizing children” (pg. 405). Scores of other such examples can be produced. Bois, like all the other KJV translators, despised the doctrine of the Anabaptists, and preached against it regularly.

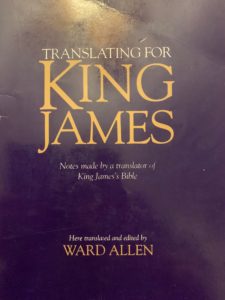

In His Translation Work

Bois is further interesting in this regard because of the notes he took during the production of the KJV. When translating I Pet. 3:21 for the KJV, Bois notes that the translators settled on the translation, “answer” in the controversial passage in I Pet. 3:21 precisely because they accepted the interpretation of Tertullian in his treatise on Baptism (echoed by the notes of Erasmus), that while there is nothing magical in the water of the laver which cleanses the body that saves, the vow of baptism is what brings spiritual regeneration. Tertullian had written (ANF, 3, pg. 669-79);

“Happy is our sacrament of water, in that, by washing away the sins of our early blindness, we are set free and admitted into eternal life!”

and,

There is absolutely nothing which makes men’s minds more obdurate than the simplicity of the divine works which are visible in the act, when compared with the grandeur which is promised thereto in the effect; so that from the very fact, that with so great simplicity, without pomp, without any considerable novelty of preparation, finally, without expense, a man is dipped in water, and amid the utterance of some few words, is sprinkled, and then rises again, not much (or not at all) the cleaner, the consequent attainment of eternity is esteemed the more incredible.

And finally,

Thus, too, in our case, the unction runs carnally, (i.e. on the body,) but profits spiritually; in the same way as the act of baptism itself too is carnal, in that we are plunged in water, but the effect spiritual, in that we are freed from sins.

Bois explained that rather than the previous English renderings, like “request,” “promise,” “agreement,” or Tyndale’s, “consenteth,” the translators specifically choose to render the word, “answer” in order to propagate the interpretation that baptism saves at the response of the baptismal vow, and they felt that “answer” would naturally call this to mind. Allen points out how the note by Bois reveals this intention of the translators and explains,

The revisers [the KJV translators] had intended that the reader understand, by the answer [i.e., the thing that saves], the baptismal vow; and certainly the meaning is clear once it is pointed out. The subject of the verse is baptism, which ‘doth also now save us.’ The soul is not saved by ‘the putting away of the filth of the flesh.’ Answerthen, is obliged to refer to the baptismal vow.

[23]

Bois’s note explains that the KJV translators translated I Pet. 3:21 the way that they did specifically so that it would affirm baptismal regeneration.

The KJV translators translated I Pet. 3:21 the way that they did specifically so that it would affirm baptismal regeneration.

The Editors Of Modern Greek Texts

Most of the modern translations listed in the comparison charts in the memes/articles being shared of versions that allegedly “remove believer’s baptism” are translating the Nestle-Aland Greek text. Kurt Aland was the major editor for that text. But he also was one of the most ardent defenders of the position that Believer’s Baptism is the only kind recorded in the New Testament. He didn’t think that this fact by itself invalidated the practice – he was fine with practicing infant baptism; he was just concerned to point out that the NT can’t be used to defend it, sine the NT gives no evidence of the practice. While the standard academic work defending Infant Baptism as a practice in the early church was by Joachim Jeremias, Kurt Aland rose to answer him, and wrote in reply a defense of Believer’s Baptism, that has been for years a standard work defending Believer’s Baptism as the position that was held by the early church.

The Translators of Modern English Translations

Further, when one goes so far as to claim that modern translators are intentionally removing Believer’s Baptism from the Bible, such allegations at some points amount to simple slander. Many of the ESV and NIV translators for example have contributed to standard works today defending Believer’s Baptism For example, Köstenberger and other ESV translators helped to write a major modern work in defense of the doctrine, seen at right. Note that such a work presents a well-reasoned, biblical defense of the Doctrine of Believer’s Baptism, and yet not one of its authors think that Luke wrote what we now call Ac.8:37. But the probably spurious vs. is not at all important to holding the doctrine, and is never invoked in the volume as support.

Conclusion

Allegations that modern translations are trying to remove the doctrine of Believer’s Baptism, while the KJV is trying to keep it, actually have the situation exactly backwards. Such allegations are simply not honest. One may certainly argue that the vs. is genuine if they so choose (note Snapp’s article above). But such accusations often don’t just argue that the vs. is genuine. They presume the vs. to be genuine, then make accusations and insinuations against modern translations and their translators for “removing” or “deleting” it, without close knowledge of the subject at hand. In some forms, this accusation is coupled with a claim that the intention is to remove Believer’s Baptism. In others, it is part of a claim that modern translations are causing “doubt” about “the availibity of Scripture.” I recognize that those that share such claims likely have good intentions. Especially in the case of Ouellette, who avoids some of the sharp edges of such accusations, for which I am grateful. I have noted before that I have great respect for him, and his service to the Lord. But as in so many other cases, he and others have likely read such claims in literature from a more extreme faction, and have shared them without bothering to check the actual data to see if they hold up. They believe they are spreading truth and supporting Scripture. But they have failed to “prove all things” as Paul commanded in I Thess. 5:20. Such accusations are based on misinformation, and are simply false. Spreading such an accusation is spreading not only misinformation, but in some cases, slanderous misinformation which is ultimately divisive. I implore them to delete the memes, articles, and any other form of such accusations, and to stop sharing them. There is no sin in ignorance or misinformation.

But a platform of ignorance and misinformation is a poor platform from which to make accusations against others.

ENDNOTES

[1] The CSB, the NKJV, and the MEV, for example, have the vs. in the text, with a footnote explaining its dubious textual support, much like Erasmus included it in 1516, but noted its dubious support.

[2] A printed Greek text used by the Greek Orthodox Church does contain the vs. It would be a mistake to assume from its presence in that text that it was a Byzantine reading, which it is not. The Greek orthodox Church is well aware that the text they currently use is not truly the “Byzantine” text which they would venerate as inspired, and requested years ago that the INTF would produce a Byzantine text actually based on the available Greek manuscripts. Currently, the INTF has only completed the gospel of John (an early electronic edition is available here http://www.iohannes.com/byzantine/index.html).

[4] Standard apparatuses are those in the NA28, UBS5, CNTTS, and the Greek data comes from the more extensive, Text und Textwert.

[5] The Text Und Textwert volume divides these into 12 basic different forms, if one doesn’t count the minor differences between the sub-forms (i.e., the presence/absence of a single word, difference in word order etc.).

[6] It is absent from the remainder of the some 660 continuous text Greek MSS. of Acts that are extant. The full list of each of these MSS. can be found in the TuT Volume, part 1, pg. 475-79.

[7] Interestingly, since the NT is a diglot presenting the text in Greek and Latin, and attempts to align the lines of text, it makes up for differences in the text length throughout the work by printing what appear to be a long series of consecutive “0”s to make up for the misaligned text. Since the Latin Vulgate text which it prints in the Latin column has the text, but the Greek text (following the Greek MSS. here) doesn’t, the Polyglot fills the section on the Greek side with these 0’s.

[8] non reperi in Graeco codice

[9] Quanquam arbitror omissum librariorum incuria

[10] Nam et haec in quodam codice Graeco asscripta reperi, sed in margine.

[11] See the edition by Hovingh, in Opera Omnia, Ordinis Sexti, Tomus Sextus, pg. 238-39, for brief discussion, who prints the full text of Erasmus’ annotation (with the later additions) as follows, “Dixit autem Philippus: Si credis etc. vsque ad eum locum Et iussit stare currum non reperi in Graeco codice. Quanquam arbitror omissum librariorum incuria. Nam et haec in quodam codice Graeco asscripta reperi, sed in margine. [CJ Caeterum apud interpretem Chrysostomum haec non adduntur. [D] Nee in aeditione Hispaniensi. In Aldina fuit additum.”

[12] His edition of the late Latin Vulgate read, “Dixit aute Philippus: Si credis ex toto corde, licet. Et respondens, ait: Credo Filiu Dei esse Iesum Christu” which is the exact form he put into his Greek text, and the exact form which then came to be translated in the KJV (Erasmus, Novum Testamentum, 1527 “VVLG. Editio” column).

[13] Brown is actually slightly mistaken at this point, for it is clear that Erasmus derived the “wording” for his insertion from the Vulgate. What he derived from 2816 (in its marginal note) was the boldness to think the Vulgate reading had some basis.

[14] Brown, Andrew, Opera Omnia Desiderii Erasmi, Oridinas Sexti, Tomus Secundas, pg. 293.

[16] See edition of his response edited by Rummel, ASD IX-4, pg. 211.

[17] While 2816 in the marginal note reads, “εἶπε δὲ αὐτῷ, Εἰ πιστεύεις ἐξ ὅλης τῆς καρδίας σου, ἔξεστιν. ἀποκριθεὶς δὲ εἶπεν: Πιστεύω τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ θεοῦ εἶναι τον Χριστὸν Ἰησοῦν,” Erasmus, putting into Greek the form found in his Latin Vulgate text, included the text in the form, “εἶπε δὲ ὁ Φίλιππος, Εἰ πιστεύεις ἐξ ὅλης τῆς καρδίας_____, ἔξεστιν. ἀποκριθεὶς δὲ εἶπε, Πιστεύω τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ Θεοῦ εἶναι τὸν Ἰησοῦν Χριστόν.” Even had Erasmus followed the form in 2816 rather than the late Latin Vulgate form, that form is only found in two Greek manuscripts.

[18] Scrivener, A Plain Introduction, 4th ed., pg. 8.

[19] Brown, Erasmi Opera Omnia, VI-4, pg. 398.

[20] “Quis autem malus genius effascinauit infelices anabaptistas?…In his familiis probabile est fuisse nonnullos infantes aut pueros.” See full text in ASD V-3, pg. 311-12, linked above.

[21] I have quoted here the translation of the sentence by Menchi in Basil 1516: Erasmus’ Edition Of The New Testament, pg. 220. See the Latin sentence underlined in an original printing here.

[22] See here and in other examples of his works.

[23] Allen, Translating for King James, pg. 27-28.

I find this statement remarkable!

“Understand – the number of Greek New Testament manuscripts that contain the exact wording of the Textus Receptus of Acts 8:37 Open in Logos Bible Software (if available) is precisely one.”

The Author’s statement is not a summary of all extant manuscript evidence. . .

There are at least 64 manuscripts including Acts 8:37 referred to by K. Aland:

“K. Aland (footnote 35) sets out the eight forms in which this verse is found in the 64 MSS he consulted, all of them minuscules except for E08 (whose singular Greek form is due to its being a retroversion of its Latin text).”

[Josep Ruis-Camps & Jenny Read-Heimerdinger, The Variant Readings of the Western Text of the Acts of the Apostles (XIV) (Acts 81b-40), Filologia Neotestamentaria, Vol. XV (2002), pages 111-132. Facultad de Filosofia y Letras – Universidad de Córdoba (España)] P. 131

Here is the footnote referenced: 35 ‘Der neutestamentliche Text in der vorkonstantinischen Epoche’, PLÉROMA. Salus carnis. Homenaje a Antonio Orbe (E. Romero-Pose ed., Santiago de Compostela 1990), pp. 66-70.

“I stood in the ocean and it rose only to my ankle.”: is a true statement, nonetheless should not be taken for an all-encompassing study.