King James Bible History

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut condimentum scelerisque dapibus. Proin eget diam euismod.

Why Does The New Testament Need To Be Continually Updated?

New editions of the Greek NT come out on a pretty regular basis. Over 1,000 different editions have been printed since 1516. Is this because the text of the NT that we have can’t be trusted? Is it because publishers just want to steal more of your money? Like an IPhone update that changes almost nothing but charges you an arm and a leg? Actually, it’s exactly the opposite.

We don’t have the original autographs of any of the NT documents. What we do have is later handwritten copies, (we call handwritten copies “manuscripts,” or mss. for short), all of which differ slightly from one another, because of errors and alterations made by each individual copyist. We use these to reconstruct the original wording of the original NT books as best we can. This “reconstruction” is known as “textual criticism” or NTTC. This data is then complied into an eclectic, printed text of the Greek NT, from which translations are then made. For the *vast* majority of the text of the NT, no “reconstruction” is necessary, because essentially all of the mss have exactly the same wording. The questions come in the small places where the mss have different wording. Even in those places, it’s not as though we’ve “lost” the Word. It’s just that we sometimes have two or more different wordings of the passage as found in various mss., and we aren’t always sure which represents the original wording, and which is a scribal alteration.

So why do these printed NT texts continue to constantly be updated? Several factors come into play;

Factors Relating To Why The NT Needs Regularly Updated

- One is the discovery of new manuscripts. Newly discovered manuscripts mean more data, which gives us a better picture of the wording of the original text of the NT. It would be irresponsible not to take into account this new data as it is discovered, even if it takes some time for data from newly discovered manuscripts to filter into editions of the Greek NT, and then from them into English translations.

- Another is a more accurate reading of the data in the manuscripts we have. For example, Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus is an important fifth century palimpsest manuscript that we’ve had for a long time. But no one was able to decipher it, so its text-critical data couldn’t be accessed or evaluated. Until a bright young scholar named Constantin Tischendorf launched his NTTC career in the 1840s by carefully examining the manuscript, deciphering its readings, and publishing the results. The manuscript had been there for a long time, but we had to get a more accurate reading of it. We continue to get better and better at reading ancient manuscripts, even those whose data seems hidden below the surface. Digitization has helped this factor immensely. We can see readings more clearly now than we once did in mss that we’ve had for a long time (and sometimes the mss. decay, making them less readable – another reason that digitization like that of Dan Wallace, the CSNTM and their mission to preserve the Word of God is so important).

- Another is the further collating of the manuscript data that we’ve always had (it’s an ongoing process – Philemon, Jude, and Revelation are the only NT books where all of the manuscript data has been completely collated). Collating is what happens when we examine every single letter of a ms. against another text to note where they differ. Every single difference of a single letter is known as a “textual variant.”

- But finally, as all this data grows, the relationships between the data are examined again and again. And our understanding of those relations continually gets tweaked by new data and continued study of old data.

- Thus, new insights are discovered, and text-critical methodology thus matures. As it matures, in slight ways, edits are made to the final text that is produced by that methodology using all that data.

A Brief History Of Updating The New Testament

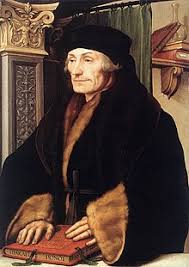

Erasmus of Rotterdam

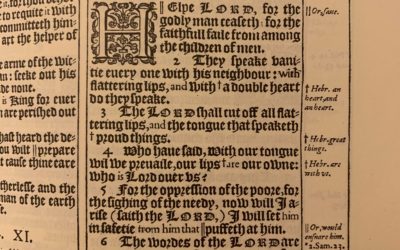

The 1535 “Annotations” of Erasmus of Rotterdam.

All of these factors have been at work since 1519. Erasmus printed a Latin/Greek diglot in 1516. It had his revision of the Latin Vulgate on one side, and the Greek text which he rather haphazardly created simply to substantiate his revisions of the Latin on the other side. While the Greek column wasn’t all that important to him, it was the first Greek NT to ever be published. And it quite literally changed the world. He added over 1,000, Annotations (like endnotes), many of which explain the many text-critical decisions he had to make when his data differed from one another. He explained how he was often not sure which reading was original. And he explained why he sometimes preferred the reading of the Latin Vulgate over his handful of Greek Mss (for example, in Acts 9:5-6, I John 5:7, and dozens of other passages). His text was a hodge-podge mixture of mostly Byzantine readings, scores of Latin Vulgate readings, and numerous minor editorial errors that wouldn’t be noticed for several hundred years (like this one in Rev. 1:8, where he accidentally deleted “God” from the text, and it didn’t get fixed till the 19th century).

But he continued to amass more data, continued to study the relationships of manuscripts to each other, and matured in his NTTC approach. Thus, another edition was required in 1519, another in 1522, then in 1527, up until 1535, when he published his final edition. His annotations pointing out textual variants and orthographical data had at least doubled in size by then, and were now printed as their own separate volume. His various editions can all be accessed here. Scrivener shared (and corrected) the evaluation of Mill about the changes in his editions (data now set out more accurately in the 10 ASD volumes);

“He estimates that Erasmus’ second edition contains 330 changes from the first for the better, seventy for the worse…that the third differs from the second in 118 places… the fourth from the third in 106 or 113 places, ninety being those from the Apocalypse just spoken of….The fifth he alleges to differ from the fourth only four times, so far as he noticed…but we meet with as many variations in St. James’ Epistle alone.

– Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Fourth Edition, 2:187.

In his Annotations, we can watch on as Erasmus begins to develop the principles of NT Textual Criticism. In fact, many of the principles of modern textual criticism find their genesis in his work, as Jan Krans points out. His work was far from perfect. But he birthed the discipline, which was still in its infancy when he published his final edition. He is clearly the father of modern New Testament Textual Criticism.

Robertus Stephanus and the Editio Regia

While starting with Erasmus as a base, Stephanus also continued to improve the text. He had more mss data than Erasmus. He ultimately included data from 16 Greek mss, including those used by Erasmus, in his apparatus (a system of abbreviations that lets an editor present mss data very concisely). This basically doubled the data Erasmus had. And the discipline matured in his handling of textual variants (reflected in his apparatus more than the text itself). Four different editions were the result, in 1546, 1549, 1550, and 1551 (see the 1550 Edito Regia here). His was the first printed Greek text to use an apparatus. Thus, while Erasmus published the first eclectic Greek text, Stephanus can be credited with printing the first critical apparatus. Scrivener notes the differnces between each edition; “My own collation of the [first two editions] gives 139 cases of divergence in the text, twenty-eight in punctuation. They differ jointly from the third edition 334 times in the text, twenty-seven in punctuation” (Scrivener, A Plain Introduction, 2:189). Stephanus’ editions can be accessed by anyone here.

Theodore Beza

Theodore Beza, the son in law of John Calvin and his successor in Geneva, took the discipline forward with his numerous marginal notes (see on any page of his works). Beza went through the same process, adding a little more mss data (he ultimately included data from 19-25 Greek mss, if we count those of Erasmus and Stephanus as well, which he had access to via the collations of Stephanus), re-evaluating textual variants, and maturing the discipline of textual criticism (again, mostly seen in his notes rather than the text itself). Thus 11 different editions (by one count) were forthcoming from him. Each edition can be accessed here. And the discipline matured a lot at his hand, as we see in his various editions and their notes. Careful study of his textual method, specifically, his conjectural emendation, is displayed by Jan Krans here. Scrivener, again, noted that early estimates of the differences between his editions were too low.

The KJV Translators As Textual Critics – Meddling With Men’s Religion

In 1604, King James I of England commissioned a revision of the 1602 edition of the Bishop’s Bible. Rule 1 specifically stated that the Bishops’ Bible taken as a base was to be revised as little as possible: “The ordinary Bible read in the Church, commonly called the Bishops Bible, to be followed, and as little altered as the truth of the Original will permit.” See an early copy of the rules in the British Library viewer for MS. BL. Add. 32092, f. 204r-v here. That revision is what we now call “The King James Bible.” (See title page in BL viewer here). The Translators made use of a handful of the numerous texts that had been produced by these three “giants” and fathers of the discipline of NTTC (they relied most heavily on the 1598 Beza, but sometimes followed Erasmus, and occasionally the Stephanus). The data they had should have made them aware of perhaps a few thousand textual variants. But they didn’t spend much time in the “scholia” (the footnotes to the printed texts explaining those variants). The more academic questions about textual criticism raised in those notes wasn’t their primary concern – producing a revision of the English Bible was.

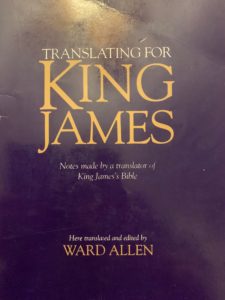

But that doesn’t mean textual issues were totally unknown. They did note scores of textual variants in the marginal notes of the 1611. And they might have noted more if not for the King’s order against notes. One of the translators, John Bois, was something of a linguistic legend. He spoke Hebrew at the age of 5, and learned Greek and Latin shortly thereafter. His mind was the stuff of legends. He exclaimed during the revision process in frustration, “Read the Greek Scholia!” He was a rare voice that thought they should be giving more attention to the text-critical issues raised in the notes of Erasmus, Stephanus, and Beza.

He also took notes during one stage of the work at Stationer’s Hall (in this room here, image 39), and they can be read today. I’ve spent quite a bit of time with them. They are laced with references to Beza and Erasmus and the text critical questions they raised. They reveal the KJV translators doing their own text-critical work that created the Greek text behind the KJV, often disagreeing with one another (he sometimes records who disagreed with who). Bois of course had his own disagreements, and published a 2-volume work evaluating the text-critical choices of Beza’s edition (which the KJV translators opted to follow more closely than any other). That is to say, he was at times critical of the textual choices that ultimately created the KJV. And he wasn’t the only one. For example, one of the greatest Hebraists of that age, Hugh Broughton, was very upset at how often the KJV chose to depart from the Hebrew Masoretic Text of the Old Testament and correct it with the Latin Vulgate and LXX.

Nonetheless, as they made numerous text critical decisions where their data differed, they ended up creating a new Greek NT text, which they never printed or published. Thus, the precise Greek text behind the KJV had never existed anywhere at that point except in their own minds.

In 1881, during the official Revision of the KJV, the Revisers were asked to set out in the margins all the places where the Greek text resulting from their textual choices differed from the Greek text behind the KJV. But his was hard to do, first, because they ended up making more changes than they had planned, and second, because the Greek text of the KJV had never been printed before, as Scrivener noted in his preface.

Ironically, this means that the Greek text behind the KJV was only ever published because of the Revised Version, and it was created by the Revisers as a companion volume to the 1881 RV. Contrary to some of the slander sometimes raised against them, no one would even have a copy of the Greek text behind the KJV had it not been for the integrity of the Revisers of 1881 and their determination to fulfill their obligations. This text was reprinted again a half-dozen times. This text stands behind, for example, Strong’s Concordance of the Bible, (Strong himself worked on the Revision as well), and all other such tools that refer to the Greek text of the KJV NT. Scrivener explained in his preface (which can be read here) what this text was and where it came from. “The special design of this volume is to place clearly before the reader the variations from the Greek text represented by the Authorized Version of the New Testament which had been embodied in the Revised Version.” He continues,

The Cambridge Press has therefore judged it best to set the readings actually adopted by the Revisers at the foot of the page, and to keep the continuous text consistent throughout by making it so far as was possible uniformly representative of the Authorized Version. The publication of an edition formed on this plan appeared to be all the more desirable, inasmuch as the Authorized Version was not a translation of any one Greek text then in existence, and no Greek text intended to reproduce in any way the original of the Authorized Version has ever been printed. In considering what text had the best right to be regarded as ‘the text presumed to underlie the authorized Version,’ it was necessary to take into account the composite nature of the Authorized Version, as due to successive revisions of Tyndale’s translation.

F.H.A. Scrivener

He notes further; “It was manifestly necessary to accept only Greek authority, though in some places the Authorized Version corresponds but loosely with any form of the Greek original, while it follows exactly the Latin Vulgate.” That is, sometimes the KJV translators ignored all of the Greek data they had to instead follow the Latin Vulgate (the Latin Vulgate thus influenced the text of the KJV at numerous stages; its influence on the Byzantine manuscripts, Erasmus’ incorporation of numerous Vug. readings into his text, and the KJV translators’ additional incorporation of even more Latin Vulgate readings). Since Scrivener refused to “back-translate” the English into Greek where none of the Greek sources the translators used had that Greek reading, even the text of Scrivener is not exactly the text behind the KJV. No such text technically exists anywhere.

And it’s worth noting, no one has ever done for the OT what Scrivener did for the NT, and so the original language text of the KJV OT has never existed in print. They deviated from their edition of the Hebrew Masoretic text in hundreds of places. Their OT text disagrees with every Hebrew Manuscript in existence, and, “to this day, no printed edition of the Hebrew Bible contains the exact Hebrew words behind the English words of the King James Version of 1611″ (James Price, King James Onlyism, pg. 254).

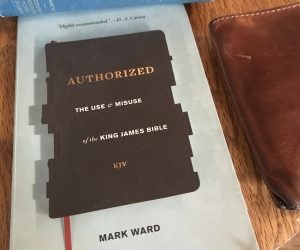

Why Claims Of Perfection For The KJV Or The TR Don’t Work

Sadly, some folks like to dishonestly claim that this Greek text is identical to “thousands” of Greek manuscripts (it actually differs from every single Greek manuscript in existence that’s of sufficient size to contain any textual variants), and promote it as the verbally perfect “preserved” words of the inspired original. Obviously, the very preface to the work by its editor poses a problem for such a position. So one publisher thus published an edition of the 1881 Scrivener TR which omits his preface, which has become the standard Greek text in KJV Only and TR Only circles. This “preface-safely-omitted” edition was the text used at the Fundamentalist Bible College I graduated from, which claimed in its doctrinal statement that this text and the KJV it translates were “the very words God inspired” now providentially preserved for all English speakers. But as John Kohlenberger noted in his lecture at the SBL commemoration of the 400th anniversary of the KJV (Kohlenberger, John R. III. “The Textual Sources of the King James Bible.” In Translation That Openeth the Window: Reflections on the History and Legacy of the King James Bible, edited by David G. Burke, 43–53. SBL: Biblical Scholarship in North America 23. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2009), “It is safe to say that, given their resources, the KJV translators worked from an eclectic text. Certainly they did not exclusively follow any one text. Nor did they, as some noncritical writers claim, limit their choices to what could be found in the texts that would later be called the Textus Receptus (TR).” David Trobisch noted (Trobisch, David. “The KJV and the Development of Text Criticism.” In The King James Version at 400 Assessing Its Genius as Bible Translation and Its Literary Influence, edited by David G. Burke, John F. Kutsko, and Philip H. Towner, 227–34. Society of Biblical Literature, 2013) in a similar vein, “Obviously, the translators of the KJV had created their own eclectic Greek text, a text that followed neither a specific manuscript nor a specific printed edition.”

Anyone who wants to claim that this text is perfect is free to do so. But such a claim requires the belief that the KJV translators were inspired by God with new revelation in their text-critical decisions. And such a claim is incompatible with a claim that this same text is the “preserved” word of God (however commonly these two words are used together by some who refer to this text). To preserve means to keep something the same, not to make it different. The Greek text of the KJVNT didn’t exists until 1611, and didn’t exists in print until 1881. If it is the verbally perfect Greek text, then this demands that God didn’t finish giving his Word until 1611. This is why I ultimately abandoned the belief that the English translation of the KJV was perfect, which I was raised on, and then abandoned the belief that the Scrivener TR was perfect, which I had been taught in Bible College.

Every form of such a position demands the belief that the KJV translators were supernaturally moved by God with new revelation.

But I was compelled by the evidence rather to the position that God had preserved his Word – not magically re-inspired it in 1611. Thus, as I often put it, I left the Shire I had been raised in (or was kicked out of it – both are sort of true).

I sometimes compare TR Only positions to the Emperor’s New Clothes. Those who hold these positions “ooh and aah” about how their position is more intelligent than their cousins who believe God inspired the English of the KJV. But they too must believe that God inspired the KJV translators with new revelation, and some kid in the crowd is bound to point out that the Emperor is still naked.

Textual Criticism Improves Beyond The KJV

But the maturing of textual criticism didn’t stop with the data from the manuscripts which informed the printed Greek texts used by the KJV translators, and their textual decisions based on that data. In fact, the KJV translators made it quite clear that they wanted revision to continue. We kept discovering more, kept looking more closely at what we already had, and kept maturing the discipline as a result. A major step was made in 1675 when data from some 80 mss was published in a new Greek text by Bishop John Fell – the most ever compared at that time.

John Mill And The Fight – Certainty Against All Evidence? Or Confidence Based On Evidence?

1707 was a landslide moment in the discipline. John Mill published his landmark text in 1707 (see here), now collating data from 100 (or some say 80) mss. The data had grown more than a hundredfold. We were now aware of some 30,000 textual variants. This created quite a stir. In reaction to what felt like the loss of certainty about the text, conservatives like Pastor Daniel Whitby and some others essentially enshrined the 1550 Stephanus text, claimed it should never be altered, and refused to consider any new data that would correct it. And, as often happens, the fear-based reactions of hyper-conservatives against historical data provided the ammo for radical skeptics to attack the faith. Skeptic John Collins immediately stepped up, using the arguments of Whitby to claim that the Christian faith was now undermined. As Tregelles later explained;

And thus in 1713 Anthony Collins, in his ‘Discourse Of Free Thinking,’ was able to use the arguments of Whitby to some purpose, in defense of his own rejection of the authority of Scripture. This part of Collins book ought to be a warning to those who raise outcries on subjects of criticism. If Mill had not been blamed for his endeavors to state existing facts relative to the [manuscripts] of the Greek Testament, and if it had not been said that thirty thousand various readings are an alarming amount, this line of argument could not have been put into Collins’s hands.

– Tregelles, 1854, An Account Of The Printed Text Of The Greek New Testament, pg. 48.

But we had so many textual variants not because the text was suddenly less stable – but because we had so much more data. Meaning the text was that much more stable. Enter classicist Richard Bentley to the fray, who explained this in 1713 very well. He rightly saw the danger of both ditches; the rejection of all evidence in favor of unfounded certainty championed by Whitby, and the skepticism unconvinced by the evidence championed by Collins. He preferred instead a confidence based upon the evidence. “Bentley had to steer clear between two points, — between those who wished to represent the text of the NT as altogether uncertain because of the variations of copies, and those who used this fact of differences to depreciate critical inquiries, and to defend the text as commonly printed against all evidence whatsoever” (S. P. Tregelles, 1854, “An Account Of The Printed Text Of The Greek New Testament”). He pointed out that our faith was founded on historical evidence, and that Christian faith is always vindicated by historical data. “Depend on’t,” he said, “no truth, no matter of fact fairly laid open, can ever subvert true religion.”

If there had been but one manuscript of the Greek Testament, at the restoration of learning about two centuries ago, then we had had no various readings at all. And would the text be in a better condition then, than now we have 30,000? So far from that, that in the best single copy extant we should have had some hundreds of faults, and some omissions irreparable. Besides that the suspicions of fraud and foul play would have been increased immensely.

It is good therefore, you’ll allow, to have more anchors than one; and another MS to join with the first would give more authority, as well as security. Now choose that second where you will, there shall still be a thousand variations from the first; and yet half or more of the faults shall still remain in them both.

A third therefore, and so a fourth, and still on, are desirable, that by a joint and mutual help all the faults may be mended; some copy preserving the true reading in one place, and some in another. And yet the more copies you call to assistance, the more do the various readings multiply upon you; every copy having its peculiar slips, though in a principle passage or two it do singular service. And this is fact not only in the New Testament, but in all ancient books whatever.

’Tis a good providence and a great blessing, that so many manuscripts of the New Testament are still among us; some procured from Egypt, others from Asia, others found in the Western churches. For the very distance of places, as well as the numbers of books, demonstrate, that there could be no collusion, no altering nor interpolating one copy by another, nor all by any of them.

….where the copies of an author are numerous, though the various readings always increase in proportion, there the text, by an accurate collation of them made by skillful and judicious hands, is ever the more correct, and comes nearer to the true words of the author.

….And so it is with the Sacred Text: make your 30,000 as many more, if numbers of copies can ever reach that sum: all the better to a knowing and serious reader, who is thereby more richly furnished to select what he sees genuine. But even put them into the hands of a knave or a fool, and yet with the most sinistrous and absurd choice, he shall not extinguish the light of any one chapter, nor so disguise Christianity but that every feature of it will still be the same.

– Richard Bentley, 1713, Remarks Upon A Late Discourse of Free Thinking, Pg. 92-113.

Dean John Burgon went back to Bentley and his brilliant assessment of the textual situation a century later when he noted;

But I would especially remind my readers of Bentley’s golden precept, that, “The real text of the sacred writers does not now, since the originals have been so long lost, lie in any [manuscript] or edition, but is dispersed in them all.” This truth, which was evident to the powerful intellect of that great scholar, lies at the root of all sound textual criticism.

– John Burgon, 1896, The Traditional Text Of The Holy Gospels Vindicated And Established, pg. 26.

Moving Forward By Going Back To Erasmus

But both Bentley and Burgon were actually simply echoing the principles of textual criticism that had been laid out by Erasmus. Erasmus faced a great deal of opposition to his “updating” of the text in his own age, especially because he often claimed that the long-trusted Latin Vulgate needed to be updated. But he adamantly maintained that we should follow the historical data wherever it leads, and that this will never jeopardize the Christian faith. He, like Bentley, recognized that the demand for textual certainty even in the face of opposing evidence was based upon an ungrounded fear, and a weak view of the Christian faith;

Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam

Do you intend to overlook all this and follow your own copy, though it was perhaps corrupted by a scribe? For no one asserts that there is any falsehood in Holy Scripture (which you also have suggested), nor has the whole question on which Jerome came to grips with Augustine anything at all to do with the matter. But one thing the facts cry out, and it can be clear, as they say, even to a blind man, that often through the translator’s clumsiness or inattention the Greek has been wrongly rendered; often the true and genuine reading has been corrupted by ignorant scribes who are half-taught and half-asleep. Which man encourages falsehood more, he who corrects and restores these passages, or he who would rather see an error added than removed? For it is of the nature of textual corruption that one error should generate another. And the changes I make are usually such as affect the overtones rather than the sense itself; though often the overtones convey a great part of the meaning. But not seldom the text has gone astray entirely. And whenever this happens, where, I ask you, do Augustine and Ambrose and Hilary and Jerome take refuge if not in the Greek original?

…There are men who do not like to see a text corrected, for it may look as though there were something they did not know. It is they who try to stop me with their authority of imaginary synods; they who build up this great threat to the Christian faith; they who cry ‘the church is in danger’ (and no doubt support her with their own shoulders, which would be better employed in propping a dung-cart) and spread suchlike rumors among the ignorant and superstitious mob…I see nothing here that much affects the genuineness of the Christian faith. If it were essential to the faith, that would be all the more reason for working hard at it. Nor can there be any danger that everybody will forthwith abandon Christ if the news happens to get out that some passage has been found in Scripture which an ignorant or sleepy scribe has miscopied or some unknown translator has rendered inadequately.

– Erasmus, Letter to Dorp, EP 337, CWE 71.

It was clear by 1707 that the discipline needed an overhaul in light of the data growing by such margins. Erasmus’ principle of continuing to revise the text in light of ever-growing data needed to be applied again, and so it was. 1707 marks a major turning point, but so on the development went, through Tregellas, Tischendorf, Hort and Westcott, Scrivener, Burgon, Aland, etc., through the major shift made in the 26th edition of the Nestle-Aland text, all the way to the present NA 28 (or the RP 2005 preferred by some). Now, we have GA numbers for 5,874 Greek NT manuscripts (the current INTF count, though the actual number of manuscripts is slightly lower). That’s an astounding amount of data compared to the few dozen or so Greek NT manuscripts that loosely formed the basis for our earliest English translations.

But we keep discovering new relics. Several of what are now the oldest papyri manuscripts for a few books of the NT have just been published within the last year. And we keep looking more closely at what we already have. And we keep plotting textual relationships in increasingly sophisticated ways, as the newer data is incorporated. And thus we keep maturing the methods and principles of NTTC in light of all this ever growing knowledge. Of course, not all scholars see things the same way. There is sometimes vigorous debate about the methods of NTTC. But we undeniably have more data than at any prior point in history, and thus more confidence about the text. As Scrivener put it in his 19th century introduction to textual criticism;

[The Quality and abundance of the manuscripts of the NT] present us with a vast and almost inexhaustible supply of materials for tracing the history, and upholding (at least within certain limits) the purity of the sacred text: every copy, if used diligently and with judgment, will contribute somewhat to those ends. So far is the copiousness of our stores from causing doubt or perplexity to the genuine student of Holy Scripture, that it leads him to recognize the more fully its general integrity in the midsts of partial variation.

– F.H.A. Scrivener, 1861, A Plain Introduction To The Criticism Of The New Testament, pg. 4.

To put it into perspective, I often point out that when the KJV translators made their text-critical choices which created the text behind the KJV, they were working with only a small percentage of the Greek manuscript data we have available today. And they stood at what was really the infancy of developing NTTC methodology. These limitations notwithstanding, they still created an excellent translation that is sufficient as the Word of God, and still in use today. In fact, I often say that every single English-speaker should own a copy. (I don’t think anyone should only use a KJV). But the discipline has matured in massive ways since then. NTTC is still exactly the same *thing* it was in 1516. We are still doing today exactly what Erasmus was doing then. The “DNA” is identical, so to speak. It has just matured such that comparing them is somewhat like comparing a small child and that same child as a grown man. Same person; just much more mature.

And at each stage texts and translations of those texts were produced which evidence the hand of NTTC at that stage. Sadly, for the first several hundred years of textual criticism, the impact of the increasing knowledge upon English translations wasn’t as great as it should have been. There was early on a bit of a disconnect between NTTC and English translations. Fortunately, that’s not as much the case today. What’s really odd though is when some folks demand that we only use the KJV, the product of 16th-17th century NTTC. The eclectic Greek text behind the KJV was the result of exactly the same kind of NTTC as that which stands behind the NA 28. There is not a single Greek Manuscript which contains the exact Greek text that stands behind the KJV.

Not one.

Not even close.

Its eclectic text is undeniably the product of NTTC – it’s just based on far less data, and is a product of the science in its infancy. Yet some act as though all the various works of a mature Picasso should be forfeited in favor of a stick figure drawing he produced as a child.

The Stability Of The New Testament Text

But perhaps most astounding, and most important, is the realization of how strikingly similar the products of each age of NTTC are to one another. Take a 1526 Tyndale NT, the first English translation of the Greek NT (a beautiful photo-facsimile is available here) and hold it next to a 2016 ESV. Compare them carefully and the thing that should most strike you is how amazingly alike they are. It’s simply astounding how 500 years of growth in NTTC has made so little change to our NT text. Not because NTTC hasn’t grown and matured. Is surely has. But because the text of the NT really is that stable and trustworthy. The more data we compile, the more textual variants we discover. The count is now somewhere around 400,000. Though this must be kept in perspective. The vast majority of these textual variants (something more than 99% of them) relate to spelling changes that in no way impact the meaning of the text, or errors that are immediately obvious as such to anyone who can read. Exactly two of these textual variants relate to passages of Scripture that are 12 verses long. A few dozen more of these textual variants relate to 1-2 whole verses of biblical text. All of the remaining textual variants are smaller than a single verse, and concern phrases, a phrase, or, most often, a single word of the text. 500 or so of them are listed in Metzger’s textual commentary, and those essentially make up the whole of most textual discussion today. In an entire sea of confidence, these reflect only a few insignificant drops of uncertainty.

The significant textual variants in the NT manuscripts are like tiny drops in the sea of confidence which the transmission tradition gives us for the text of the New Testament.

The number and type of textual variants that exists don’t mean we are less confident of the wording of the original text. On the contrary, we are more sure of it than ever before. And it’s absolutely amazing how stable and trustworthy the transmission of the NT text is now found to have been through the millennia. Whatever minor discrepancies can be found in every manuscript, everyone who ever read any Greek NT manuscript (and anyone today who uses anygood translation of the text) still has possession of a trustworthy and sufficient copy of the Word of God, which still proclaims the same message, and the same doctrines. Given 2,000 years of transmission history under every conceivable condition, that reality is, I think, a clear mark of the providential concern of God to preserve the text.

What’s most astounding about the updates of textual criticism over 500 years is how amazingly little the printed text of our NT has needed altered. The NT text is simply amazingly stable.

But minor details continue to be tweaked. Thus, updates will continue to be required if scholars want to be accurate and careful with the exact words of the text. And those who respect Scripture as God’s Word should be especially concerned to give attention to every single word of the text.

The Scope Of Continued Updates

These updates are now typically incredibly minor compared to the “landmark” shifts of a few centuries ago. And barring some unforeseen astounding new discovery, will continue to be rather minor. Even the radical skeptic Bart Ehrman (who has risen to fame as North America’s most well-known skeptic because of the doubt he raises about the text of the New Testament), has admitted that the text of the New Testament is for all practical purpose rather settled at this point, and won’t likely ever receive another massive overhaul unless unforeseen extraordinary data comes to light. While he might express himself differently today, in a major scholarly publication in 2012, he acknowledged;

“Textual scholars have enjoyed reasonable success at establishing, to the best of their abilities, the original text of the New Testament. Indeed, barring extraordinary new discoveries or phenomenal alterations of method, it is virtually inconceivable that the character of our printed Greek New Testaments will ever change significantly.”

(The Text Of The New Testament In Contemporary Research, 2nd ed., pg. 825).

There’s simply not likely to be any rather radical changes. For example, the differences between the NA 27 and the NA 28 amounted to only 30+ changes to the actual text of the NT which it printed.

But of course, we could always assume, as a few have, quite vocally at times, that none of this is true, and that new updates are just a way to steal money out of your pockets. An odd (and perhaps slanderous) claim, given that the German Bible Society now makes the NA text freely available online. Giving something away free isn’t usually the best strategy for stealing money out of someone’s pockets.

Scholars continue to have slightly different opinions about how to put the data together. This is why rather than just one Greek text, there are several that are employed by different scholars of different stripes. Like the RP one here (which has gained little traction among scholars), the standard one here, or the relatively new one here. I would love to see good English translations made of each of these modern texts, which would then reflect better in English the kind of difference of opinion that modern textual critics sometimes have about the shape of the original text. Most English translations today are from the NA text. But in any case, minor updates will continue to be made to the text of the NT, for all of the reasons above. Not because we are trying to get further away from the original New Testament, but because we are trying to get closer and closer to the original wording of the original text, and the small gap between what they wrote and what we read gets increasingly smaller with every new generation.

These updates then are not a bad thing. They don’t undermine our faith in the NT. Rather, they simply make us all the more confident that we have the very word of God. They help us tweak our understanding of those words and our printing of them in the minor ways. And thus they help us print the original text of the New Testament with greater and greater precision and confidence.

Daniel 3:25 And “The Son Of God” In The KJV

We all know the story of the three Hebrew children thrown into the fiery furnace in Daniel chapter three. In fact, some of you are singing “I’m Rack, I’m Shach, I’m Benny!” even as I mention it. (Shame on you vegetable lovers!) Surely, the image of the fourth man in the fire is a continually comforting one to the believer enduring trials. When three faithful Hebrew refused to bow to an idolatrous image, King Nebuchadnezzar followed through on his threat to throw them bound into the fiery furnace. He knew he only threw three men in, bound. But he found four men, unhurt, and unbound.

Who Was This Fourth Man In The Fire?

The text reads;

“Then Nebuchadnezzar in furious rage commanded that Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego be brought. So they brought these men before the king.Nebuchadnezzar answered and said to them, “Is it true, O Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, that you do not serve my gods or worship the golden image that I have set up? Now if you are ready when you hear the sound of the horn, pipe, lyre, trigon, harp, bagpipe, and every kind of music, to fall down and worship the image that I have made, well and good. But if you do not worship, you shall immediately be cast into a burning fiery furnace. And who is the god who will deliver you out of my hands?”

Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego answered and said to the king, “O Nebuchadnezzar, we have no need to answer you in this matter. If this be so, our God whom we serve is able to deliver us from the burning fiery furnace, and he will deliver us out of your hand, O king. But if not, be it known to you, O king, that we will not serve your gods or worship the golden image that you have set up.”

Then Nebuchadnezzar was filled with fury, and the expression of his face was changed against Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. He ordered the furnace heated seven times more than it was usually heated. And he ordered some of the mighty men of his army to bind Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, and to cast them into the burning fiery furnace. Then these men were bound in their cloaks, their tunics, their hats, and their other garments, and they were thrown into the burning fiery furnace. Because the king’s order was urgent and the furnace overheated, the flame of the fire killed those men who took up Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. And these three men, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, fell bound into the burning fiery furnace.

Then King Nebuchadnezzar was astonished and rose up in haste. He declared to his counselors, “Did we not cast three men bound into the fire?” They answered and said to the king, “True, O king.” He answered and said, “But I see four men unbound, walking in the midst of the fire, and they are not hurt; and the appearance of the fourth is like a son of the gods.”

Then Nebuchadnezzar came near to the door of the burning fiery furnace; he declared, “Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, servants of the Most High God, come out, and come here!” Then Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego came out from the fire. And the satraps, the prefects, the governors, and the king’s counselors gathered together and saw that the fire had not had any power over the bodies of those men. The hair of their heads was not singed, their cloaks were not harmed, and no smell of fire had come upon them. Nebuchadnezzar answered and said, “Blessed be the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, who has sent his angel and delivered his servants, who trusted in him, and set aside the king’s command, and yielded up their bodies rather than serve and worship any god except their own God. Therefore I make a decree: Any people, nation, or language that speaks anything against the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego shall be torn limb from limb, and their houses laid in ruins, for there is no other god who is able to rescue in this way.” Then the king promoted Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego in the province of Babylon.”

(Daniel 3:13–30 ESV)

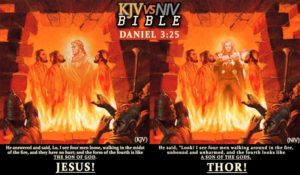

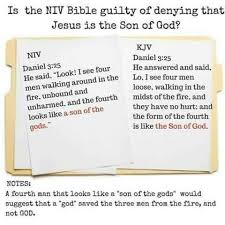

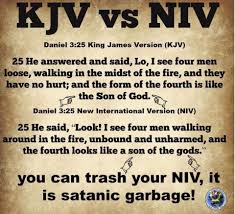

The KJV, differing from the ESV quoted above, claims that, “the form of the fourth is like the Son of God” (Dan. 3:25 KJV), which is a direct statement about Jesus, the Second Person of the Trinity, being in the fire with the Hebrew children. On the other hand, the NIV, and most other modern translations, read something like, “and the appearance of the fourth is like a son of the gods (Dan. 3:25 ESV).”

I regularly see comparisons of Dan 3:25 NIV/KJV in my news feed. A meme comparing them seems to go around every so often in “seasons.” One form suggests that the NIV has “taken Jesus out” of Daniel 3:25, and that this is a “big deal.” I even recall hearing one pastor tell me that this passage is “the” reason why we should all use the KJV instead of other translations, because the KJV points to Jesus, and all the others have “removed Jesus” from the passage! Examples are easy to find with a simple google search, variously claiming that the NIV promotes Thor worship, denies the deity of Jesus, or is “satanic garbage” as a result of its reading in Dan. 3:25;

What is really going on here? Which translation is right? Who really was the fourth man in the fire? Is this really such a big deal? And is it a matter that justifies the kind of language in such memes?

First, I’d say to those sharing sharing memes like that one, or raising the question, in one sense, thank you for sharing the post. I think comparing translations like that can be very helpful. The King James translators, (in their preface defending the practice of placing thousands of alternate translations in the margins) noted that,

Therefore as St. Augustine saith, that variety of Translations is profitable for the finding out of the sense of the Scriptures: so diversity of signification and sense in the margin, where the text is not so clear, must needs do good, yea is necessary, as we are persuaded.

Augustine knew that there is no perfect way to translate much of Scripture, and had suggested that the wise reader always compare different translations to make sure that he understands the sense of Scripture, not just the interpretation of the translator. The KJV translators quite agreed, as do I. So again, thank you for sharing. I think it’s important to understand why translations differ in any particular instance, so that we can understand what’s at work behind the scenes.

There are actually two different questions at issue when we come to the questions of this passage. The first is the theological one – that is, who do we understand the “fourth man in the fire” to have been? We might call this the question of theological interpretation. The second is the related, but distinct, matter of how to translate the phrase the King uses to refer to him. This might be considered the question of who the King regarded the being to be, and which perspective should be reflected in an English translation of the phrase, or the exegetical interpretation.

Who Was In The Fire? – The Question Of Theological Interpretation

As to the first question, “Who was in the fire?”, it may surprise some readers to know that this is a highly debated matter among commentators. There is a long tradition in Christian history of identifying the “fourth man” as a theophany, or, more particularly, what is sometimes called a “Christophany” (an appearance of the pre-incarnate Christ). This interpretation of the text goes back a long way in church history, and for many conservatives, it is probably the only understanding of the passage they are familiar with. But there is an (even longer) tradition of Jewish commentators (and Christian commentators who follow their lead) that identify the being with some other angelic being or form of divine presence or agent (often along the lines of the common “Angel of the LORD” found at various points throughout the OT). James Montgomery, in the Older ICC volume, notes that, “As to the theological interpretation of the son of God, the Jewish commentators identify him simply as an angel…”. But he also notes that, “Early Christian exegesis naturally identifies the personage with the Second Person of the Trinity…But this view has been generally given up by modern Christian commentators” (ICC, Daniel, pg. 215).

Goldingay, in the more recent WBC volume, notes that the phrase, “might for Nebuchadnezzar suggest an actual god. Similarly God’s aide [the angel of the Lord] might signify in effect God himself; cf. Yahweh’s [angel], e.g., Exodus 3:2. Isaiah 43:1-3, indeed, has promised God’s own presence when Israel walks through the fire. Nevertheless to Jews [the Hebrew phrase son of the gods/Son of God/Divine being] would indicate a subordinate heavenly being. Cf. the supernatural watchman…of [Daniel] 4:10, 14, 20 [13, 17, 23], and the humanlike heavenly interpreters and leaders of chapters 7-12. In such a context God’s [angel], too, will denote a non divine heavenly being” (Goldingay, John, WBC “Daniel,” pg. 71).

Tremper Longman puts an even finer point on the question.

That God rescued the three Jews no one is in doubt, but who was that ‘fourth [who] looks like a son of the gods” (v. 25)? As in chapter 2, Nebucadnezzar is moved from anger to praise toward God and his followers. In his concluding speech, he again mentions the mysterious fourth person. When he first saw the figure, he labeled him ‘a son of the gods’; now he calls him God’s ‘angel’ (v. 28). His dual description has launched a debate that continues to the present day…we must remember that the narrative places these two descriptions in the mouth of Nebuchadnezzar, who is not an Israelite theologian. Relying on his words, we are thrown into a quandary: was this God himself as ‘son of the gods” might lead us to believe, or an angel? In one sense, it does not make any difference. Even if the fourth figure was an angel, it was God’s angel; God is still the redeemer. Even Nebuchadnezzar recognizes this. He further acknowledges that the three have been right to obey this God rather than a king like him.

– NIVAC, Daniel, Pg. 102-103.

He later takes up the question again, and asks,

Where does the Christian…find the moral and religious strength to make such a courageous stand? From Jesus Christ. Jesus himself was put on trial for his religious claim that he was the Messiah. Facing death himself, he refused to capitulate, dying on the cross (cf. Matt. 27:11-14). But was Jesus at the heart of the hope of the three friends as they faced death in the furnace? It is difficult to say how specifically their hope focused on the coming Savior, the Messiah. They trusted in the saving power of God, but it is provocative to reflect on the way God choose to deliver the three from the fire. Calvin pointed out that if God wanted, he could have extinguished the flames of the fire in order to save the three men. He saved them in the fire, not from the fire. They were in the very jaws of death. Moreover, he could have saved them without further fanfare, simply having them walk out of the fire unscathed, but instead chose to save them by the presence of a ‘fourth [who] looks like a son of the gods” vs. 25).

Was this ‘fourth’ being Jesus, as many interpreters from the earliest Christian times have suggested? It is impossible to be dogmatic unless one insist that every incarnate appearance of God must be the second person of the Trinity. It is safer to say that what we have here is a reflection of Immanuel, ‘God with us.’ God dwelt with the three friends in the midst of the flames to preserve them from harm. In this sense, the Christian cannot help but see a prefigurement of Jesus Christ, who came to earth to dwell in a chaotic world and who even experienced death, not so that we might escape the experience of death but that we might have victory over it.

– NIVAC, pg. 112.

How Should We Translate The Phrase? – The Question Of Exegetical Interpretation

When we approached the theological question, we asked only who was actually in the fire, from our later and more mature vantage point. And it turns out, that’s a controversial question, and we can’t say for sure, though we can be sure that the point of the text is the same either way – God walks with us through the fire. But even if we concluded that it was in fact the pre-incarnate Christ who was in the fire (a position I lean towards), that does nothing to settle the second question. That is, how should the phrase referring to this fourth man be translated in our English Bibles? The reason this is so is because it is generally agreed that the purpose of a translation is to give the meaning of the text as understood by its original author, not as it came to be interpreted in later Christian times. Let me explain.

Translating The Text

The text being translated by both the NIV and the KJV at this passage is exactly the same. It is an Aramaic section of the Masoretic text. The KJV translators were using the 1525 Bomberg edition of the Hebrew text, the NIV was using the more modern BHS, but both are identical at this point (and almost all others). The text reads a simple three-word phrase;

דָּמֵ֖ה לְבַר־אֱלָהִֽין׃ ס

Or, literally, “like a son of the gods.” The word for “God/gods” is elohin, the Aramaic (Chaldee) equivalent of the Hebrew Elohim. The word is plural, not singular, so grammatically speaking the NIV is being more literal by translating it with a plural (“gods”) rather than a singular (“God”). But sometimes, when used of the one true God, the word can be plural in form but singular in meaning (somewhat like what’s known as a “plural of majesty”). Although it has been argued that such a singular sense is actually grammatically impossible here in this instance (see the note in Goldingay’s WBC commentary, pg.67). More often it is a true grammatical plural, referring to “gods.” HALOT, the standard Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon for biblical studies, notes that the word can refer to “the God of Israel” but also can refer (2ba) to “the gods of other nations (in Daniel always Babylonian gods)” and notes that the Masoretic Text has it as a plural here, “preferring the idea that Nebuchadnezzar was a polytheist,” and they note that in this passage it refers to “a divine being, an angel.”

One can see several uses of this word in this very passage, to get a sense of the difference. For example, in 3:14 the KJV translates the same word “gods,” then in 3:17, the same word as “God,” and again in 3:18, it is “gods” in the KJV. All of these are the same word. Both “God” and “the gods” (and even “angel”) are legitimate translations at times. Probably either is possible here. The context and intent of the speaker is the key.

So what is the context, and who is the speaker? It is important to remember, as Tremper Longman pointed out above, that verse 25 is not in the mouth of Daniel as a narrator and biblical writer. This is not Daniel’s description of what he sees in the fire. Rather, the words are on the mouth of the pagan King, Nebuchadnezzar. Daniel (who is not present in this story, but nonetheless narrates it as an inspired historian) is a good historian. He reports what happened accurately, without embellishment, and without exaggeration. So what happened historically? The King saw another being in the fire with the three children, and spoke of it according to his own viewpoint, from his own limited understanding. From his viewpoint, what he saw was, “a son of the gods.” This common phrase simply meant an angel or “divine being” of any kind (see Goldingay, WBC, pg. 64). Daniel makes clear in verse 28 that what Nebuchadnezzar thought he saw was just such a being;

Then Nebuchadnezzar spake, and said, Blessed be the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, who hath sent *his angel,* and delivered his servants that trusted in him, and have changed the king’s word, and yielded their bodies, that they might not serve nor worship any god, except their own God.

The king thought it was an “angel” or a divine being, what he would refer to as “angel” or a “son of the gods.”

Tracing Historic Translations Of The Text

Thus, for example, the Coverdale Bible of 1535 translated the phrase in verse 25,

“and the fourth is like an angel to loke vpon.”

The Geneva Bible rendered the text;

“and the forme of the fourth is like the sonne of God.”

but left a study note that explained that this actually was just another way to refer to an angelic being of any kind;

For the Angels were called the sonnes of God, because of their excellencie: therefore the Kīg called this Angel, whome God sent to comfort his in these great torments, the sonne of God.

The Matthew’s Bible of 1549 that revised it likewise read,

“and the fourthe is lyke an angell to loke vpon.”

The Bishop’s Bible, likely following the Geneva Bible, had changed this to,

“and the fourme of the fourth is like the sonne of God.”

The KJV is itself simply a revision of the 1602 Bishop’s Bible, which reads as above, “like the sonne of God,” but adds a marginal note to clarify what is meant, “That is, an angel of God.” Normally, when revising the Bishops text, they just left the text the same. But here, they chose to remove the marginal note, leaving “sonne of God” in the text without capitalization.

The 1611 KJV reads essentially the same as the Bishop’s Bible here, and clearly means the same thing, but without the clarification of its note. That is, the 1611 KJV intends to teach that this was an angelic being, not that this was Christ. But they removed the marginal note of the Bishop’s text which made this clear. This created an ambiguity that a later editor missed. At some point (after 1638, the latest old edition I checked, but before the Scrivener 1873 Cambridge Paragraph Bible), the meaning of the phrase “son of God” as an angelic being was lost, and “Son” was capitalized, thus making it a reference very directly and specifically to Christ.

These translations from Bible’s preceding the KJV should do away with any slanderous claim that the NIV is attempting to “remove Jesus” from the passage here. Jesus wasn’t in the passage in English in the KJV in 1611, and wasn’t in the passage at all in English Bibles until a later editor misread the KJV!

Note that Daniel reported what was actually said historically, not our later and more accurate theological interpretation of what was actually taking place. Today, as Christians, we can look back with a full Bible and a full revelation, and we understand a doctrine called the Trinity. We know that the one true God is a three-in-one Being; Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. But this was not yet revealed in Daniel’s time (in a later vision for example, Daniel sees “the Ancient of Days” or God, and “the Son of Man,” a different mysterious figure who Jesus later revealed prefigured Himself). God’s revelation unfolds over time. The revelation that the single God Yahweh has a Son who shares fully in His Divine name would not take place until Jesus came in the incarnation, and it didn’t come first to a pagan King. If Nebuchadnezzar had actually said, “Look! The one true God has a Son who is also God!” then God would have been giving revelation about himself to a pagan King that he wouldn’t even give to His own people until some 500 years later. I think it rather unlikely that such a pagan King had a higher revelation from God (and in any case, verse 28 in the KJV makes clear that he did not). As Christians with full revelation, we can know Who was in the fire. But as translators, one could make the case that we should respect Daniel’s own intentions as a biblical writer. Daniel was a good historian, and we should not, in my opinion, create an instance of him being a bad historian (interpreting rather than reporting what the King had said).

John Calvin took a similar track as the Geneva note listed above, understanding that “son of a god/God” was simply a way of referring to an angelic being, and arguing that Nebuchadnezzar could not have understood otherwise. He explained;

John Calvin

But Nebuchadnezzar says, four men walked in the fire, and the face of the fourth is like the son of a god. No doubt God here sent one of his angels, to support by his presence the minds of his saints, lest they should faint. It was indeed a formidable spectacle to see the furnace so hot, and to be cast into it. By this consolation God wished to allay their anxiety, and to soften their grief, by adding an angel as their companion. We know how many angels have been sent to one man, as we read of Elisha. (2 Kings 6:15.) And there is this general rule—He has given his angels charge over thee, to guard thee in all thy ways; and also, The camps of angels are about those who fear God. (Ps. 91:11, and 34:7.) This, indeed, is especially fulfilled in Christ; but it is extended to the whole body, and to each member of the Church, for God has his own hosts at hand to serve him. But we read again how an angel was often sent to a whole nation. God indeed does not need his angels, while he uses their assistance in condescension to our infirmities. And when we do not regard his power as highly as we ought, he interposes his angels to remove our doubts, as we have formerly said. A single angel was sent to these three men; Nebuchadnezzar calls him a son of God; not because he thought him to be Christ, but according to the common opinion among all people, that angels are sons of God, since a certain divinity is resplendent in them; and hence they call angels generally sons of God. According to this usual custom, Nebuchadnezzar says, the fourth man is like a son of a god. For he could not recognise the only-begotten Son of God, since, as we have already seen, he was blinded by so many depraved errors. And if any one should say it was enthusiasm, this would be forced and frigid. This simplicity, then, will be sufficient for us, since Nebuchadnezzar spoke in the usual manner, as one of the angels was sent to those three men—since, as I have said, it was then customary to call angels sons of God. Scripture thus speaks, (Ps. 89:6, and elsewhere,) but God never suffered truth to become so buried in the world as not to leave some seed of sound doctrine, at least as a testimony to the profane, and to render them more inexcusable—as we shall treat more at length in the next lecture.

– John Calvin and Thomas Myers, Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Daniel, vol. 1 (Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 2010), 230–231.

That’s not to say I’m demanding that we “correct” the modern KJV here. Far from it. The KJV in its modern printing is explaining quite accurately the theological truth of the Trinity. The KJV does not accurately present what Daniel intended when he wrote, but it does accurately reflect an Anglican, orthodox understanding of the Trinity, as developed and expressed long after Daniel’s time. Probably, one could read the verse from the KJV, and just read vs. 28 to clarify what the King thought he saw, and Who we know was really there. But at the least, the NIV should certainly not be attacked here for translating the same text in a more literal way grammatically, and for representing Daniel as being an accurate historian who didn’t creatively interpret what he recorded, but accurately wrote what was said, rather than putting words in someone’s mouth that they likely didn’t utter.

Both translations should by understood for what they intend to do, and neither deserves censure at this point, (contra the memes that go around suggesting that this difference is a “big deal” or is “removing Jesus”). The NIV is translating what the King actually said. If one wants their translation to reflect the intent of the original biblical author, the NIV is spot on at this point. The KJV is interpreting that statement not as it was originally spoken but as it came to be understood by later Christian theologians. If one wants their translation to reflect later theological formulations from the 17th century, the KJV is spot on at this point. Both can be valid in some ways.

But Didn’t Nebuchadnezzar Adopt Jewish Monotheism?

An interesting article making similar points as I have made here can be found at KJVOnly.org here. An attempt to defend the KJV reading, which I think quite fails, can be read at the KJV Today site here. Note that it is essential to that defense that the King did not mean to say that the fourth man in the fire was Jesus. So the KJV Today article is no support for an attack on the NIV for “deleting Jesus” or any such thing. However, the KJV Today article attempts to claim that since Nebuchadnezzar uses the phrase, “the most high God” in verse 26, he must of necessity have been referring to the monotheistic understanding of the Jewish God. This would still miss the point that Jewish monotheism is not Christian Trinitarianism, but even as much as it says is not technically accurate. Goldingay points out,

The title ‘God Most High’ (vs. 26) is another expression at home on the lips of either a foreigner (3:32; 4:14; 31 [4:2, 17, 34]; Gen. 14:18-20; Num. 24:16; Isa. 14:14) or a Jew (Dan. 4:21-29 [24-32]; 5:18, 21; 7:18-27; Gen. 14:22; Deut. 32:8; Psalms), though its nuances for each would again differ. To both it suggests a God of universal authority, but of otherwise undefined personal qualities. For a pagan [like Nebuchadnezzar], it would denote only the highest among many gods, but as an ephitet of El it was accepted in early OT times and applied to Yahweh, so that for a Jew it has monotheistic (or mono-Yahwistic) implications.

– WBC, pg. 71-72.

And Baldwin, among many other voices, likewise agrees, noting;

This title for God is often found in the mouth of non-Jews (Gen. 14:19; Num. 24:16; Isa. 14:14). There is nothing unlikely in the edict, which does no more than declare legal in the empire the religion of the Jews.”

– Baldwin, J. G. (1978). TOTC Daniel: An Introduction and Commentary (Vol. 23, p. 118). Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

What Does The Story Say To Us Today?

Regardless of how we answer both of the questions above, the point of the passage remains the same for us as believers. Daniel is writing his work near (or just after) the end of the Babylonian captivity of the children of Israel. This surely was one of the more difficult experiences of their existence. And Daniel knew that they would need reminded that even in their chastisement, God was never apart from them. And so he recounts for them the story they had told already for a generation. A story of the proto-typical time, in their recent memory, when God had shown that he never abandons his children to face the fire alone. He walks with them through it, just as he had promised (Is. 43:1-3). As Calvin noted, he saved them in the fire, not from it. And this has always been his way with his children who suffer in this broken and fallen world. He still saves in the fire. Goldingay notes,

The king who thought that no god could save the confessors from his power is the one who now perceives God’s intervention….The three have not been delivered from the fire, but they are delivered in the fire (c.f. Rom. 8:37) (Phillip). The life of blessing and success that is their destiny is reached, not by way of costless and risk-free triumph but by the way of the cross. They are free, looking as if they are enjoying a walk in the garden… It is four unbound (vs. 25) who contrast with three bound. The deliverance comes about through the presence of a fourth person in their midst. The divine aide who camps round those who honor God and extricates them from peril (Ps. 34:8 [7]) enters the fire himself to neutralize its capacity for harm by the presence of his superior energy. God’s promise, “I will be with you” characteristically belongs in the context of afflictions and pressure (Exod. 3:12; Isa. 7:14; 43:1-3; Matt. 28:20; see also Ps. 23:4-5). The experience of God’s being with his people not only follows on their commitment to him, rather than preceding it; it comes only in the furnace, not in being preserved from it…

– WBC, pg. 74-75.

Tim Keller points out, in words that can conclude our brief look at the text;

In perhaps the most vivid depiction of suffering in the Bible, in the third chapter of the book of Daniel, three faithful men are thrown into a furnace that is supposed to kill them. But a mysterious figure appears beside them. The astonished observers discern not three but four persons in the furnace, and the one who appears to be ‘the son of the gods.’ And so they walk through the furnace of suffering and are not consumed. From the vantage of the New Testament, Christians know that this was the Son of God himself, one who faced his own, infinity greater furnace of affliction centuries later when he went to the cross. This raises the concept of God ‘walking with us’ to a whole new level. In Jesus Christ we see that God actually experiences the pain of the fire as we do. He truly is God with us, in love and understanding, in our anguish. He plunged himself into our furnace so that, when we find ourselves in the fire, we can turn to him and know we will not be consumed but will be made into people great and beautiful. ‘I will be with you, your troubles to bless, and sanctity you to your deepest distress.’

– Walking With God Through Pain And Suffering, pg. 9-10.

A Misguided Command To “Abstain” In The KJV (Part II)

In our last post we examined the KJV translation of Paul’s command in I Thess. 5:22 as, “abstain from all appearance of evil.” We explained the idea found in some circles that in the realm of ethics, even if an activity isn’t inherently wrong, if it might appear wrong to others, it must be avoided. This idea has had disastrous consequences when this verse has been abused. We pointed out that Shogren explained that the KJV rendering here, “has been the basis for what is virtually a special branch of ethics, that a believer should refrain from any practice which might appear to be evil, typically to another Christian, although in theory, to any person whatever. This has led to the principle that one’s behavior should be guided by the perception of others…” (ZECNT, pg. 227). We then showed that this idea is in fact what the KJV translators meant to convey in their translation of the verse, not a misunderstanding of the KJV. We traced out two different broad categories of interpretation in history; what we have called the “ethical” and the “prophetic” interpretations. The KJV translation represents one small strand of the ethical interpretation.

But now we raise the much more important question – What did Paul actually mean?

What Was Paul Saying?

To understand Paul’s meaning, we will first zoom in on the word translated “appearance” in the KJV, discuss the arguments for the ethical interpretation, and then examine the context of the verse.

The Word “Appearance/Form/Kind”

We start with a close look at the word εἴδους (eidous), translated in the KJV “appearance.” BDAG, the standard NT Greek lexicon, provides three possible meanings for the word;

① the shape and structure of something as it appears to someone, form, outward appearance

② a variety of something, kind

③ the act of looking/seeing, seeing, sight

The first question is whether Paul has the first or second meaning in view (see also LSJ for other uses of this classical meaning). And even if he has the first meaning in view, one must still make a case that he intends the outward appearance to be something not corresponding to reality if one wants to arrive at the KJV. The KJV took him as referring to something that only outwardly appears evil, but is not inherently so. Note that this is only one shade of the first meaning. But it is far more likely, given the context, that he is talking about something that actually is evil, not something which only appears to be so. He is thus talking about forms or kinds of evil, not a mere “appearance” of evil. Moises Silva explains in the NIDNTTE;

The exhortation in 1 Thess 5:22… has traditionally been rendered, “Abstain from all appearance of evil” (KJV), but it is almost certain that here the term has its common class[ical] meaning, “kind, type, form”…

– Moisés Silva, ed., New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology and Exegesis, pg. 97.

Dan Wallace, we saw last time, wrote an extremely helpful blog post on the passage (all quotes of Wallace here are from that post). Following a suggestion in Kittel, (and with some support from a few Apostolic Fathers) he argues that perhaps a more rare meaning of the word, “to mint a coin” is at play;

Significantly, the noun…(used in this verse) is sometimes translated “mint.” Along these lines, what is interesting to note is that in the early church, the wording of 1 Thess 5:21 was more often attributed to Jesus than to Paul. And it was prefaced by the words “become approved money-changers.” This then was followed by the participial construction, “by abstaining from evil things and by holding fast to the good.” Thus, Paul may well be quoting from a previously unrecorded saying of Jesus in 1 Thess 5:21-22. If so, then these verses need to be rendered as follows: “Test all things; hold fast to the good, but abstain from every false coinage.” The idea then is that believers ought to stay away from that which is counterfeit–that is, false doctrines.

Ethical Interpretations Without The “Mere Appearance” Twist

Whether that intriguing proposal by Wallace is accepted or not, there is still no real reason to assume that Paul means to refer to behavior which appears evil but is not. The ethical interpretation can certainly be held without such a notion, and often has been. For example, Charles Spurgeon held to the ethical interpretation, but suggested that the KJV was wrong to translate the passage as referring to behavior which only appears evil. While doing a verse by verse exposition of the whole chapter, he wrote of this verse;

By which is not meant as some read it, “from everything that somebody likes to say looks like evil.” This would be to mar the Christian liberty. But wherever evil puts in an appearance, when it appears to be good, when it has been dressed out—for the word may refer to a Roman spectacle, or grand procession. Avoid evil even when dressed out in its best, when it comes on in all its gallant show to attract you. Avoid every species and kind of evil—that might almost be the translation—abstain from it altogether.

– C. H. Spurgeon, “Joy in Salvation,” in The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit Sermons, vol. 62, pg. 132.

What About The Lack Of Connectives?

In my opinion, the arguments for the ethical interpretation are weak and unconvincing. The one thing that might be said for an ethical interpretation is to note how sparse verbal connectives are in this list of commands by Paul, as though he meant them to be treated in isolation. Even so, we do have a clear one connecting verse 20 to 21, in the Byzantine and Standard modern texts at least. (It is absent from the Greek text of the KJV NT and all the TR editions I checked, perhaps one more factor which might have affected their misreading of the text.)

Beza 1598, I Thess. 5:14-23.

Beza, 1598, I Thess. 5:23-28.

As we saw last time, the KJV interprets and translates the verse as though it stood isolated from its surrounding context, I think quite mistakenly. But they cannot be alone blamed for this. When the Stephanus text first versified the NT, its editor had rendered exceptionally small verses in this entire section, treating the staccato commands here as unconnected to one another. Beza had followed suit in his texts, and so when verse divisions came into English Bibles, this exegetical decision had already been somewhat made for the reader. Gone now were Tyndale’s well-thought out paragraphs.

Tyndale 1526, I Thess. 5:6-20a.

Tyndale 1526, I Thess. 5:20b-28.

The Bishops Bible which the KJV revised had done the same thing, followed the same small verse divisions here, and printing each as a separate paragraph. The KJV Translators all had copies of this text in front of them as they did their revising work. The King had ordered 40 unbound copies of this text to be purchased from Richard Barker for them to work on. We still in fact have the receipt for the purchase today.

So, in a way, the visual layout of their text was already subconsciously affecting the way they read the text. It would have been quite an unexpected turn for them to have seen these commands as connected in any way, given their textual resources, and the patterns their eyes were already leading them to see.

1602 Bishops’ Bible, I Thess. 4:7-5:28.

But does the lack of connectives actually mean that Paul was intending to give a series of disconnected commands? Wallace explains in a footnote that this doesn’t in fact mean that Paul meant them to be read in isolation. Asyndeton (i.e., lack of connection), can serve a variety of functions in the NT. Sometimes such constructions are used to heighten the emphasis of the implicit connection. He notes the example of Phil 4:5, where Paul says, “Let your forbearance be known to all men. The Lord is near.” These two sentences are clearly connected. Also, Wallace notes, in Eph 4:4-5,

after Paul had just instructed the Ephesians about maintaining the unity of the Spirit, he says, “[There is] one body and one Spirit,… one Lord, one faith, one baptism.” Is there no connection between vv 1-3 and vv 4-6? On the contrary, vv 4-6 offer the theological basis and pattern for what Christian unity should be like. In 2 Tim 3:16, Paul reminds Timothy that “Every Scripture is inspired and profitable.” Such a solemn statement surely has a connection with v 15: “You have been acquainted with the sacred writings from your childhood.” Thus, asyndeton does not necessarily or even normally imply no connection. Often, it is used to heighten the connection with what was previously mentioned. We believe that that is the case in 1 Thess 5:19-22 as well.

In any case, even if one found the ethical interpretation convincing, there is no clear reason to take the “even the mere appearance” of evil form of this interpretation found in the KJV. Still less would there be grounds for the common use of this verse to build and bulwark hosts of unbiblical commands. God simply didn’t intend for you to lead your life held captive to the conscience of others, and still less to live your life more concerned about what they thought of you than what he did.

Keeping The Verse In Its Historical And Literary Contexts

The basic differences between ethical and prophetic interpretations of the passage are the result of whether or not the surrounding context shapes our reading of the verse. The peculiar “mere appearance” form of the ethical interpretation has virtually nothing to commend it, though broader ethical interpretations may have more weight. What ultimately convinces me (and virtually all modern interpreters) of the prophetic interpretation are the historical and literary contexts. Whatever one might think about the continuation/cessation of prophecy today, no one can deny its presence at Thessalonica in the NT era in which Paul wrote. As Chrysostom well said, “There were among them many indeed who prophesied truly, but some prophesied falsely,” and this reality created a need for a balanced response by Paul, which would neither denigrate prophecies nor accept them all gullibly.

This historical reality is precisely the issue Paul raises in the immediate literary context when he commands not quenching the Spirit/despising prophecies in verse 19-20, and specifically urges the testing of prophecy in verse 21. The connective δὲ (de), “but,” explicitly connects his command about “testing all” to the “prophecies” of verse 20.