- “The KJV is the only Bible that isn’t copyrighted!”

- “Modern Versions are simply a greedy money game!”

- “The KJV is the only Bible that missionaries can make copies of for free!”

- ”The only reason that versions other than the KJV even exists today is because publishers legally have to change a percentage of words in order for a copyright to make money, and modern version publishers only care about money.”

These and similar claims can be found in practically every piece of literature that claims to defend the KJV as the preserved word of God for the English-speaking people. Or just glance around the internet, here, here, here, here, or scores of other places. It seems almost par for the course to claim that the KJV is the “only English Bible not copyrighted” and that all other modern versions are thus inferior to the KJV for this reason. I remember hearing preachers while I was a teen railing about how this was because the KJV represented “God’s words” and all other Bibles were “man’s words.” One cannot copyright “God’s words,” of course. And that’s why the KJV is the only version not copyrighted. In fact, when I’ve taught on the KJV before, lines full of people have assembled, each taking their turn to inform me that I was wrong to suggest that the KJV is not perfect, and the basis for their rebuttal was that clearly I didn’t realize that it is the only English translation not copyrighted. How could I have missed this clear proof that the KJV is perfect? Such a sentiment about copyright is odd both because it would be irrelevant even if it were true, and, more importantly, because it is blatantly false.

An Example From A Trusted Source

R.B. Ouellette wrote what is, in my opinion, one of the best of the books defending the KJV. I respect him, and his work for the gospel, greatly. I quote him here because he’s in a different category than the kind of internet propaganda making such claims that one can find so easily. And I always believe in dealing with the best forms of an argument. That’s why I interacted with his work here, rather than with the scores of “crazies” that would have made easy targets. In fact, we used his book as a required text in Grad School at the Fundamentalist Bible College I attended. Many who defend the KJV are kind, gracious, well-meaning believers who love God. I count many of them my friends. But they often end up repeating the claims of a more radical wing of KJV defenders, without bothering to research whether such claims are true. They typically are not malicious – they simply have neglected their biblical responsibility to “prove all things” (I Thess. 5:19-22). I suspect this is one such example, where otherwise intelligent people are simply repeating absurd claims without bothering to check them out. My guess is that Ouellette is simply repeating here what he has read and assumed true, without really bothering to verify it. Ouellette writes, in a lists of “false statements,” these words about the KJV, “False Statement: The King James Bible is copyrighted,” [Bold original] and then strangely, proceeds to contradict himself and show that his statement is actually not a false one, and that the KJV is in fact copyrighted. He claims that the copyright on the KJV is only to protect the text, and asserts that, “This entire approach is different from the copyrights held today on modern Bible versions. The modern versions are tightly controlled by secular publishing companies for the primary purpose of revenue” (R. B. Ouellette, A More Sure Word, pg. 149). But he is grossly mistaken at almost every point here.

First, as Oullette would construe it at least, Cambridge University Press has a copyright on the KJV (which we will examine below) which produces revenue. His language, intended to be pejorative, sets a double standard. Second, his statement about modern versions being tightly controlled for the primary purpose of revenue is an unforgivable generalization. He cannot see the motives of every publisher. He cannot even see the motives of any publisher. He is not God. Such incredibly sweeping statements are false and unwarranted accusations, being made without multiple evidences provided. Accusations such as this should not be made lightly. Biblically, one should not believe such a statement until documented evidence from every single modern version is produced (see Deut. 19:15). But beyond even these basic problems with his claims, standing behind them lies a serious ignorance of basic facts of history, to which we now turn.

The Greedy Printers Of The KJV

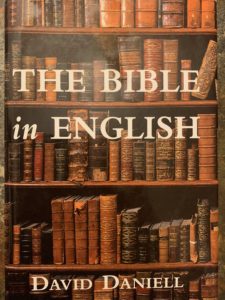

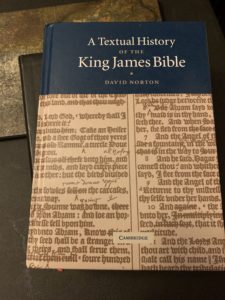

In fact, modern scholars of the KJV, who study the history of the English Bible as a career, generally agree that revenue and profit were major factors in why the KJV became the most widely used version for many years. David Norton and David Daniell have penned some of the most important works on the history of the English Bible to come about in the last several decades (perhaps even the last century). Daniell explains that it was the commercial ability of the KJV to reward its printer that led to its fame;

…contrary to what has been confidently asserted for several centuries, this version [the KJV] was not universally loved from the moment it appeared. Far from it. As a publication in the seventeenth century it was undoubtedly successful: it was heavily used, and it rapidly saw off its chief rival, the three Geneva Bibles, to become the standard British (and American) Bible. But that success was at first for political and commercial reasons, and largely a result of in-fighting between London printers. For its first 150 years, the KJV received a barrage of criticism.

– David Daniell, The Bible In English, hereafter, BIE, pg. 429.

Robert Barker, the King’s printer, held the monopoly on printing Bibles (of any kind). And he incurred some serious money problems. Thus, he needed cash, and cash fast. But the KJV was far easier and cheaper to print than the Geneva Bible that was still the most loved Bible of the people, or the Bishop’s Bible, which was the officially accepted Bible of the clergy. Further, it could be claimed to have been the product of a royal enterprise (whether it was ever officially “authorized” is an open debate among scholars). The revision of the 1602 Bishop’s Bible that had been made in 1611, what we now call the King James Bible, wasn’t really loved more than the Geneva and Bishop’s Bibles. It may not even have been liked by comparison. But it was a great moneymaker, because it was far cheaper to produce and an easier sell. A dirty squabble over who would be able to profit from this cash cow immediately ensued upon its first printing. The details of the first few years are sparse, though Daniell notes, “…the business of the printing of the KJV became almost at once devious, and at times, vicious.” (Daniell, BIE, pg. 451). Serious legal battles, involving preposterous amounts of money, soon ensued. People were jailed, bankrupted, sued, countersued, etc. Daniell pointedly explains,

What was being fought over was the marketing of a new Bible in which interest was high, one that could, in fact, easily be reprinted. The market would be helped by it being said to be a royal enterprise, in a way that no previous English Bible had been. The tight group of spitting enemies, four men and one woman, (Christopher’s wife) were the only people allowed to print the the KJV, and they would be united only in the desire to keep profits as high as they could be…The fighting became total war…

– Daniell, BIE, pg. 455.

When Bookseller Michael Sparke began importing Bibles to avoid paying the high costs, and defeat the monopoly, Robert Barker obtained a warrant to seize these Bibles. Printers who tried to get into the money making scheme had their equipment seized. This ugly “battle for the Bible” continued, but it was, ultimately, a battle for moneymotivated by avarice. Daniell summarizes, noting that the KJV as a new translation, “triumphed because it was commercially manoeuvred to do so, not because it was new. Perhaps enough has been said here to remove the idea of an automatic instant triumph of KJV based entirely on its ‘glorious beauty.'”

[The KJV] triumphed because it was commercially manoeuvred to do so, not because it was new.

– David Daniell

David Norton explains the same reality, sharing further details of the story. He is worth quoting at length here;

David Norton explains the same reality, sharing further details of the story. He is worth quoting at length here;

The last regular edition of the Geneva Bible was published in 1644. Thereafter, to buy a Bible meant to buy a King James Bible. Other versions continued in circulation, but gradually the commercial identity of ‘English Bible’ and ‘King James Bible’ became also a popular identity: with only one major version available, this was inevitable. In spite of the later perception of the KJB’s superiority, this publishing triumph owed nothing to its merits (or Geneva’s demerits) as a scholarly or literary rendering of the originals: economics and politics were the key factors. It was in the very substantial commercial interest of the King’s Printer, who had a monopoly on the text, and the Cambridge University Press, which also claimed the right to print the text, that the KJB should succeed. In the trial of the man principally responsible for suppressing the Geneva Bible, Archbishop Laud, (1573-1645), there is a report that because the KJB, described as ‘the new translation without notes’, was ‘most vendible’, the King’s Printer forbore to print Geneva Bibles for ‘private lucre, not by virtue of any public restraint [and so] they were usually imported from beyond the seas’. ‘Most vendible’ probably means most profitable to the King’s Printer, since Robert Baker had invested substantially in the KJB. The Geneva Bible appeared more marketable, and its continued importation was not just for sectarian reasons but because there was a popular demand.

Norton goes on to cite Laud and his argument that the Geneva was a threat commercially because it was a “better” Bible which could be sold more cheaply, “And would any man buy a worse Bible dearer, that might have a better more cheap?” He picks up the story with Michael Sparke:

The Puritan Michael Sparke, a London bookseller and importer of Bibles in defiance of the monopoly, publisher too of Laud’s opponent William Prynne, gives an identical picture in his attack on printing monopolies… He documents price rises, notes how much cheaper the imported Bibles are, and charges the King’s Printer with commercial exploitation of his monopoly. Like Laud, he writes in several places of the ‘better paper and print’ of the imports. Ironically, then, the KJB’s triumph over its rival came about in part because it was an inferior production: in fair competition it would probably have lost, but its supporters had foul means at their disposal.

– David Norton, A History of the English Bible as Literature, pg. 90-91.

Ironically, then, the KJB’s triumph over its rival came about in part because it was an inferior production: in fair competition it would probably have lost, but its supporters had foul means at their disposal.

– David Norton

One can consult Daniell’s chapter, “Printing the King James Bible,” or Norton’s breathtakingly detailed, “A Textual History Of The King James Bible” for more of the sordid story that makes up this soap opera. Or his two-volume, “History of the Bible as Literature.” Even purchasing his inexpensive condensed volume will give one some of the picture. But for now, it is enough to note that charges that modern publishers of modern versions, with the sole exception of the KJV, are driven by greed and avarice are in fact pointed in exactly the wrong direction. Such accusations are far more true of the printing of the KJV. Scholars of the KJV today agree that the KJV’s ultimate popularity and move from a disliked to a beloved Bible translation was in fact largely due to this greedy profit game.

Are All Modern Versions Really Just The Product Of Greedy Publishers Out For money?

How does the history of the KJV compare to modern versions? Are all modern versions really just a money game? Contrast the story above for example with the NET Bible, which was an endeavor of great cost, but is given “free for all, for all time.” Its intention was to be globally free, something the KJV is not now, and never has been. The editors explain in the preface,

In the second year of bible.org’s ministry (1995) it became clear that a free online Bible would be needed on the bible.org website since copyrighted Bibles can’t be quoted in a huge collection of online studies. The NET Bible project was commissioned to create a faithful Bible translation that could be placed on the Internet, downloaded for free, and used around the world for ministry. The Bible is God’s gift to humanity – it should be free. (Go to www.bible.org and download your free copy.) Permission is available for the NET Bible to be printed royalty-free for organizations like the The Gideon’s International who print and distribute Bibles for charity. The NET Bible (with all the translators’ notes) has also been provided to Wycliffe Bible Translators to assist their field translators. The NET Bible Society is working with other groups and Bible Societies to provide the NET Bible translators’ notes to complement fresh translations in other languages. A Chinese translation team is currently at work on a new translation which incorporates the NET Bible translators’ notes in Chinese, making them available to an additional 1.5 billion people. Parallel projects involving other languages are also in progress.

One can in fact print the entire NET Bible for free, anywhere in the world, and hand it out. One cannot do that in the UK with the KJV (and one could not do that anywhere else in the world, if the British Crown happened to rule the whole world). These godly editors of modern publishing houses (and many others like them) simply do not deserve the accusations of avarice that have been leveled against them by the generalizations of Ouellette and others.

Modern Internet Licenses

But beyond examples like the NET Bible ministry model, and other translations that are intentionally produced for free use, or made freely available, practically every single modern version has provided license to various internet sites to make the entire text of their version entirely free online. The NIV, NKJV, ESV, NET, NASB, HCSB, CSB, RSV, NRSV, GNT, LEB, NLT, The Message, and scores of other modern versions have given away their text digitally for free, despite all the high cost of production, so that the text can be freely accessible to anyone with internet access. Even the German Bible Society’s exorbitantly expensive Nestle-Aland text has been made freely available by the publisher online! Websites like BibleGateway.com, BibleHub.com, BlueletterBible.org, and others, as well as free Apps like YouVersion, make the texts of these versions free to all. In the face of such free access, it is hard to claim, as Ouellette has, that “modern versions are tightly controlled by secular publishing companies for the primary purpose of revenue.”

But besides even that point, as my friend Mark McDonnell has noted, where did anyonone get the idea that a publisher cannot, or should not, charge for their work producing a Bible? That’s not a biblical notion at all. Probably most of us who have a KJV Bible have in fact paid money for it (I’ve spent hundreds on some of my copies!). And Moses, Jesus, and Paul, all explicitly taught that, “The labourer is worthy of his reward,” and has a right to be paid for his work, even those spreading and propagating the very gospel message itself (1 Tim. 5:18, KJV See also Matt. 10:10; Luke 10:7; Lev. 19:13; Deut. 24:15; 1 Cor. 9:4, 7–14).

The KJV And Royal Patents

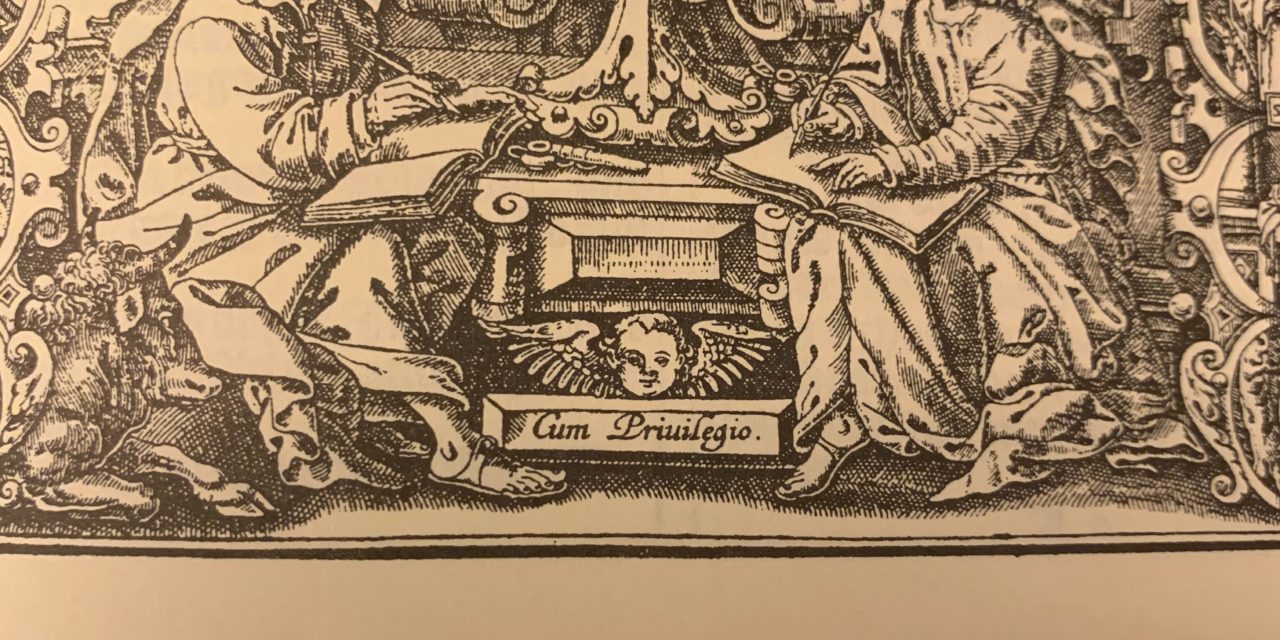

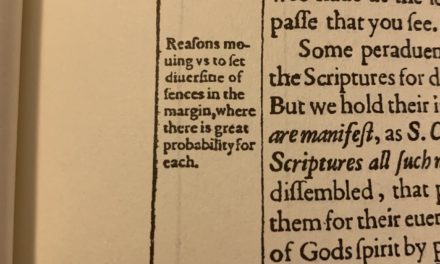

When the KJV was printed, the United States’ Constitution’s “copyright clause” did not yet exist. Copyright Law wasn’t a thing. But that doesn’t mean that pre-cursory rights equivalent to copyright didn’t exist. The first edition of the KJV was printed with the Latin words, “cum privilegio” or “with privilege” at the bottom of its title page for the New Testament (Viewable here, or see the image above). This was the common practice to identify the royal priviligia of printing. The Barkers as royal printers held the printing rights of the Crown or the “Privilege” of printing it, at least initially. And they had a financially beneficial monopoly on printing it. Alister McGrath explains,

The English book trade was regulated by the Stationers’ Company. As printing was permitted only at four centers—London, York, Oxford, and Cambridge—until 1695, regulation of the trade was not especially difficult. The printing of Bibles, however, was seen as a matter of particular importance, and was subject to additional regulations. Since the time of Henry VIII, Bibles printed within England by official sanction—such as Matthew’s Bible, the Great Bible, and the Bishops’ Bible—were subject to a trade monopoly. The monarch granted a “privilege” to favored subjects allowing them a monopoly on the production of certain types of Bible—an honor or favor usually indicated with the words cum privilegio on the title page of the Bible in question. The crown, in turn, received a proportion of the “royalty” paid to the holder of the privilege.

– McGrath, Alister. In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, a Language, and a Culture, pg. 197-198.

He goes on to explain much of the same narrative that Norton and Daniell laid out above, noting that “Barker’s support for biblical translations appears to have been directly proportional to their profitability” (McGrath, p. 198). Ouellette, in his bold attempt to claim the KJV is unique among English Bibles, asserts that, “For the purposes [sic] of protecting the text, the King James Version of the Bible was originally copyrighted and still is in the United Kingdom” (Ouellette, pg. 149). But McGrath rather explains that, “…the use of the King’s Printer for this important new translation did not rest upon any perception that this would ensure a more accurate or reliable printing, but upon the belief that this was potentially a profitable project that would bring financial advantage to Barker and his partners” (McGrath, pg. 199). Costs were cut in every way. Proofreaders were minimized (which led to the numerous, infamous abundance of printing errors, detailed by Norton in the work linked above, like “The Wicked Bible“). And the rights of printing were fought over. Because the KJV was a profitable industry, and printing it was about making money.

The rights of printing it are still today held by the Crown, the same Crown that produced it. It was always, from its first printing in 1611, only allowed to be printed, “with privilege.” The royal patent was extended later to Oxford University Press, and Cambridge University Press. While there has been some vicious back-and-forth over the years, especially in the early years, both of these publishers still hold derived rights to print the KJV. Cambridge explains their royal right of printing (or patent) in what functions as the modern copyright to the KJV, which they have held since the first copy rolled off their presses in 1629. It states;

KING JAMES VERSION

Rights in The Authorized Version of the Bible (King James Bible) in the United Kingdom are vested in the Crown and administered by the Crown’s patentee, Cambridge University Press. The reproduction by any means of the text of the King James Version is permitted to a maximum of five hundred (500) verses for liturgical and non-commercial educational use, provided that the verses quoted neither amount to a complete book of the Bible nor represent 25 per cent or more of the total text of the work in which they are quoted, subject to the following acknowledgement being included:

Scripture quotations from The Authorized (King James) Version. Rights in the Authorized Version in the United Kingdom are vested in the Crown. Reproduced by permission of the Crown’s patentee, Cambridge University Press.

When quotations from the KJV text are used in materials not being made available for sale, such as church bulletins, orders of service, posters, presentation materials, or similar media, a complete copyright notice is not required but the initials KJV must appear at the end of the quotation.

Rights or permission requests (including but not limited to reproduction in commercial publications) that exceed the above guidelines must be directed to the Permissions Department, Cambridge University Press, University Printing House, Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge CB2 8BS, UK (http://www.cambridge.org/about-us/rights permissions/permissions/permissions-requests/) and approved in writing.

(http://www.cambridge.org/bibles/about/rights-and-permissions)

Cambridge Press further explains at their website;

Rights in the Authorized (King James) Version of the Bible and Book of Common Prayer

In the United Kingdom, rights in the Authorized Version of the Bible (AV), also known as the King James Bible or King James Version (KJV), are Crown copyright. Only a small number of publishers have entitlement to reproduce the KJV.

Cambridge University Press is responsible for administering the Crown’s rights in the KJV in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Cambridge first published an edition of the Authorized Version in 1629 and has been publishing it ever since. The Latin term ‘cum privilegio’ is printed on the title pages of Cambridge editions of the KJV and the 1662 Book of Common Prayer (BCP), to denote the charter authority or privilege under which they are published.

There have only ever been at any one time three bodies entitled to print the KJV and BCP in England: the university presses of Cambridge and of Oxford (who similarly have a charter which entitles them to publish and print as a Privileged Press) and the Royal Printer. In addition to its own privilege, Cambridge has also been the owner since 1990 of Royal Letters Patent as The Queen’s Printer: as such, Cambridge is entitled both to print and publish the KJV and the BCP, and also to control or license their publication on behalf of the Crown. The Scottish Bible Board has similar delegated authority in respect of the KJV in Scotland.

The primary function for Cambridge in its role as patent-holder is preserving the integrity of the text, continuing a long-standing tradition and reputation for textual scholarship and accuracy of printing. As a university press, a charitable enterprise devoted to the advancement of learning, Cambridge has no desire to restrict artificially that advancement; commercial restrictiveness through a partial monopoly is no part of our purpose. We grant permission to use the text, and license printing or the importation for sale within the UK, as long as we are assured of acceptable quality and accuracy.

Oxford University Press notes their right, granted by the Crown, to print the KJV;

The University also established its right to print the King James Authorized Version of the Bible in the seventeenth century. This Bible Privilege formed the basis of OUP’s publishing activities throughout the next two centuries.

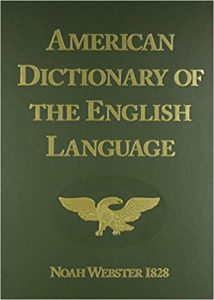

Copyrights In English Dictionaries

The OED defines “copyright” as “The exclusive right given by law for a certain term of years to an author, composer, designer, etc. (or his assignee), to print, publish, and sell copies of his original work.” For those who strangely prefer it, the Webster’s 1828 English dictionary defines, “Copyright” as,

COPYRIGHT, noun The sole right which an author has in his own original literary compositions; the exclusive right of an author to print, publish and vend his own literary works, for his own benefit; the like right in the hands of an assignee.

The patent or “privilege” that was granted to the KJV on its title page, and is still retained today by Cambridge, fits the definition of a “copyright” as listed in the Webster’s 1828. The KJV is and always has been a copyrighted work.

The KJV – An Un-American Bible?

There is a sense of course in which the KJV can be considered in the “public domain” in the U.S. As noted in legal journals here and here. But it must be noted that this is, historically, simply a function of America at the Revolutionary War choosing to ignore the crown and its laws. As Syn explains (pg. 12 at the above link) “In the United States, after the War of Independence of 1776, English patents were disregarded. This caused the Authorised Version – still protected by royal patents – to enter the public domain outside the United Kingdom.” Cohn likewise explains (pg. 52 at the link above) that, “upon winning the Revolutionary War in 1776, however, the United States disregarded all English patents, and everything under these patents, including the KJV Bible, fell into the public domain. When the Constitution was ratified, all the works in the public domain remained in the public domain.”

Perhaps some have imagined that the KJV was produced in America, and must therefore have an American copyright if that copyright is to mean anything. But it was not produced here, and we didn’t even exists as a nation yet in the age of its production. It is not an American book. Had it been, it would be copyrighted here, and someone would still retain that copyright. The fact that there is no U.S. copyright, and that the copyright is held in the U.K. rather than the U.S. (and is ignored in the U.S.) is a factor of the KJV not being an American production. This does not in any way shape or form make the KJV superior, or point to it alone being the Word of God in English. This doesn’t make the KJV God’s only words in English; it simply makes it un-American in its origins. In fact, its continual stress upon the Divine Right of King’s makes it still today stand in sharp contradiction to the very revolution that birthed America. That is, the KJV is not only not an American Bible in its origins – it could rightly be called an un-American Bible.

A Concluding Comment

Frankly, whether the KJV did or did not have a copyright is a rather irrelevant issue. It has literally nothing to do with the question of whether the KJV is a perfect translation, or a perfect text, or the preserved Word of God for English speaking peoples. But for some reason this issue keeps being brought up by people who think this somehow proves that the KJV alone represents “God’s words.” And this often happens along with slanderous broad-brush accusations being made against modern publishers, many of whom (not all, admittedly) are made up of good and godly men. These good men do not deserve to be so accused and attacked. Slander is sin. Anyone repeating this slanderous accusation should confess and repent of it.

The KJV is, and always has been, held under Copyright.

The KJV is, and always has been, held under copyright. That’s not a bad thing. It just means that the KJV, unlike the NET Bible and a few exceptions noted above, is in this respect like most other English Bibles. It may be a special and unique work. In fact, I think it is, and I often say that I think every English-speaking Christian should own and read a copy of the KJV (though I don’t think anyone should use only a KJV). But it is not unique or special on the basis of some alleged absence of a copyright. Here, it must blend into the crowd of other English versions, and stop pretending to stand head and shoulders above the rest.

I disagree with your article. First, in what way is the Geneva Bible better than the AV? I have a Geneva Bible and find it interesting because of the commentaries. But the AV is much better when it comes to preaching. The beauty and power of the language is second to no other version. Also the GB has numerous commentaries from well known Calvinists. That’s fine with me up to a point, since I am a five-point Calvinist. But I think commentaries belong in a separate volume, not alongside the revealed text of the Holy Bible.

If the GB was superior to the AV, then in my opinion it would have more readers. How many Christians actually even have a GB? If there was a demand, there would be a supply. Also the ones I have seen are outrageously expensive. Although it is also available on CD as a digital scan.

My church uses only the AV. I would not even set foot inside a church that used any other version. This is not simply because it is superior as literature. The AV was based on the most reliable manuscripts. All other versions since then have used unreliable manuscripts. In addition, their editors were not necessarily Bible believers. Quite the contrary.

My final comment will perhaps make you think I am a fanatical KJV only sort of person. Not at all. I am a Christian who believes the Bible is the inspired, infallible, inerrant Word of God. If I knew of a more reliable version than the AV, I would use it. The fact is, none exists.

No, you may not have my email address. None of your business.